A Light for the Ages

In the heart of ancient Alexandria once stood a monument to the highest aspirations of the human spirit—the Library and Musaeum of Alexandria, a place where science, philosophy, art, and culture converged in one of the world’s first truly international centers of knowledge.

Scholars came from across the known world, not to dominate or divide, but to share ideas, challenge assumptions, and illuminate truth. It was an era defined not by walls or weapons, but by inquiry, dialogue, and reverence for the natural world.

Today, in an age equally filled with complexity and promise, Science Abbey draws inspiration from this noble legacy. We are not a temple of marble, but a living “monastery without walls”—a sanctuary of learning open to all. We are building a community guided by Scientific Humanism, a worldview that unites evidence-based reasoning, universal human dignity, environmental responsibility, and the transformative power of education.

This article explores the intellectual brilliance of the ancient world—from the birth of medicine and mathematics to the philosophical systems that first glimpsed the shape of the cosmos. It traces the rise of early scientific inquiry through Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, China, Greece, and Rome—and reflects on what was lost in the destruction of Alexandria’s great library, and what we must preserve and protect today.

Science Abbey’s mission is not merely to remember this past, but to revive its spirit—through free civic education, a global community of learners, and a commitment to truth, reason, and ethical progress. As we explore this golden chapter of human civilization, may we be reminded that the pursuit of knowledge is not a luxury or a privilege, but a sacred trust. One that we are honored to carry forward.

Alexander the Great and the Birth of Alexandria

Alexander III of Macedon (356–323 BCE), better known to history as Alexander the Great, was a brilliant military commander and visionary empire-builder.

The son of King Philip II of Macedon, Alexander was educated by none other than Aristotle, the great Greek philosopher and student of Plato. This early tutelage imbued the young prince not only with a hunger for conquest but also with an admiration for learning, culture, and the pursuit of universal knowledge.

At the age of twenty, Alexander ascended to the throne and quickly proved himself a formidable force, unifying the Greek city-states under Macedonian rule. With unrelenting ambition, he launched a sweeping military campaign that would stretch from Asia Minor to Egypt, across Babylonia and Persia, and as far east as the Indus Valley in India.

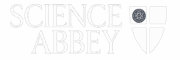

In 332 BCE, as part of his war against the Persian Empire, Alexander conquered Memphis, then the ancient capital of Egypt. Rather than rule from this historic seat, Alexander envisioned a new city on the northern coast—a cultural and strategic outpost that would serve as a maritime link between Greece and Egypt, Europe and Asia, and ultimately, West and East.

Thus was founded Alexandria, a city destined to become one of the greatest centers of learning and civilization in the ancient world.

The Rise of a Cultural Capital

After Alexander’s untimely death in 323 BCE, his vast empire splintered among his generals. Control of Egypt fell to Ptolemy I Soter, one of Alexander’s most trusted companions. Ptolemy declared himself Pharaoh and founded the Ptolemaic Dynasty, which would rule Egypt for nearly three centuries.

Under Ptolemaic rule, Alexandria flourished—not only as a hub of commerce and naval power, but as a beacon of intellectual and cultural enlightenment. Ptolemy and his successors, continuing Alexander’s admiration for learning, undertook the ambitious construction of the Mouseion, or “Temple to the Muses”—a grand research institution that would evolve into the world’s first great university.

At the heart of this intellectual citadel stood the Library of Alexandria, a vast repository of ancient knowledge that aimed to collect every book in the world. The Ptolemies dispatched agents across the known world to acquire scrolls, texts, and codices in every language, especially Greek. The library’s ambitious vision was nothing less than to catalogue the totality of human knowledge.

Scholars, Science, and the Spirit of Inquiry

Alexandria quickly attracted the brightest minds of the Hellenistic age. Among them:

- Euclid, the father of geometry, who wrote The Elements in Alexandria.

- Archimedes, who developed early concepts of physics and mathematics.

- Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism, who shaped centuries of philosophical and mystical thought.

- Eratosthenes, the chief librarian, who famously calculated the circumference of the Earth with remarkable accuracy.

- Claudius Ptolemy, the geographer and astronomer whose Almagest influenced cosmology for over a thousand years.

The Mouseion and Library functioned as more than just places of study—they were centers of scientific experimentation, literary production, philosophical discourse, and religious synthesis. The cult of Serapis, blending Greek and Egyptian spiritual traditions, was promoted by the early Ptolemies as a unifying symbol of their cosmopolitan reign.

A City of Cultures and Controversies

Alexandria was not only a city of scholars but a melting pot of peoples. It hosted a thriving Jewish community, whose most enduring contribution was the creation of the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. This made Jewish scripture accessible to the broader Hellenistic world and would later shape early Christian thought.

However, Alexandria’s rich diversity also brought interethnic and interreligious tensions, as Greek, Egyptian, Jewish, and later Christian communities competed for influence and recognition in the city’s vibrant, often volatile public life.

The Fall of the Great Library

The Library of Alexandria, legendary in its scope, suffered a tragic fate. Its main collection was most likely destroyed in the course of civil conflict during the Roman emperor Aurelian’s siege of the city in the late 3rd century CE. A secondary “daughter library,” located within the Temple of Serapis, endured until 391 CE, when it too was destroyed amid rising religious hostilities.

Though the original building and most of its contents are lost to time, the spirit of the Ancient Library of Alexandria lives on in the enduring ideal of a world where knowledge is preserved, shared, and celebrated.

The Death of Alexander and the Legacy of Hellenism

Alexander the Great, after forging one of the largest empires in ancient history, met an untimely and mysterious end. In 323 BCE, at the height of his power, the conqueror died in Babylon at the age of thirty-two, likely from typhoid fever, though some sources have long speculated poison or malaria. His death left a vacuum of authority—he named no clear successor, and his infant son was too young to rule.

What followed was a turbulent period known as the Wars of the Diadochi, in which Alexander’s generals divided the empire among themselves. From the wreckage of his conquests emerged several Hellenistic kingdoms, each ruled by one of his former commanders. The most enduring of these was the Ptolemaic Dynasty in Egypt, founded by Ptolemy I Soter, which ruled for nearly 300 years.

Though politically fragmented, Alexander’s cultural legacy endured. His campaigns had not only redrawn the political map of the ancient world—they had sown the seeds of Hellenism, a vibrant fusion of Greek, Egyptian, Persian, Central Asian, and Indian cultures.

This remarkable epoch, known as the Hellenistic Age, lasted until the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE, when Cleopatra VII—the last of the Ptolemies—was defeated by Octavian (later Augustus), and Alexandria became a jewel in the Roman crown.

Hellenism’s influence extended far beyond the Mediterranean. In the East, Greek cultural and artistic styles mingled with Indian spiritual traditions, giving rise to Greco-Buddhism—a striking synthesis visible in the elegant sculptures of Buddha created in regions like Gandhara. These Greco-Buddhist kingdoms played a pivotal role in transmitting Buddhist philosophy along the Silk Road, the sprawling network of trade routes established during China’s Han Dynasty in the 2nd century BCE.

Merchants, monks, and scholars journeyed across this transcontinental highway, carrying not just silk and spices, but art, science, and religion. In this cultural crossroads, ideas flowed freely between East and West, and the world grew more connected than ever before.

At the heart of this globalizing world stood Alexandria, the glittering beacon of learning founded by Alexander himself. Dominating the city’s skyline was the Lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, rising an estimated 100 meters above the harbor.

Yet the greatest treasure of Alexandria was not its monumental lighthouse, nor even its strategic port—but the Musaeum, or Temple of the Muses, and its renowned Library of Alexandria. It was here that the knowledge of the ancient world was collected, preserved, and studied—an enduring symbol of intellectual curiosity, scientific inquiry, and the dream of universal wisdom.

The Nine Muses inspiring Arion, Orpheus and Pythagoras (Pythagorean theorem) under the auspices of the Personified Air, source of all Harmony, 13th century, Public Library Rheims.

The Musaeum of Alexandria: A Temple of Knowledge

At the heart of ancient Alexandria stood one of the most extraordinary institutions the world had ever known: the Musaeum of Alexandria—or Mouseion, the “Temple of the Muses.” Founded in the early 3rd century BCE by Ptolemy I Soter—a former general of Alexander the Great and founder of the Ptolemaic Dynasty—or possibly by his son, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the Musaeum was the intellectual crown jewel of a rapidly rising city.

This was no ordinary building. Unlike today’s museums, which display relics and artifacts, the original Musaeum was more akin to a modern research university or think tank—a state-sponsored sanctuary for scholars, scientists, poets, and philosophers, dedicated to the advancement and preservation of human knowledge.

Modelled after Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum, the Musaeum was designed and directed by Demetrius of Phaleron, a former Athenian statesman and philosopher, who had studied under Aristotle himself. Demetrius envisioned a place not only to store knowledge, but to cultivate it—to build a self-sustaining community of intellectuals engaged in continuous discovery, debate, and education.

The Musaeum was richly supported by the royal treasury. Resident scholars were relieved of financial burdens: they received a tax-exempt salary, free housing, meals, and even servants, allowing them to focus solely on their work. Like monks in a monastery, they lived communally and owned no personal property, dedicating their lives to learning.

At the heart of this scholarly haven was the famed Library of Alexandria, a marvel of ancient ambition that sought to collect every book in the world. Its mission was encyclopedic: to gather the full body of human knowledge, in every language, from every known land. Agents of the Library traveled across the Mediterranean and Near East to acquire texts—buying them, copying them, or even seizing them from ships docking at Alexandria’s ports.

It was said that the library contained hundreds of thousands of scrolls—Greek, Egyptian, Persian, Indian, and more—each one studied, edited, and translated by experts in residence. Scholars in the Musaeum advanced work in astronomy, mathematics, medicine, philosophy, geography, linguistics, and literature, establishing standards that would shape intellectual history for centuries.

The administration of the Musaeum was overseen by a chief priest, appointed first by the Pharaoh and later by the Roman Emperor, signaling the Musaeum’s quasi-sacred status. To direct knowledge was to direct destiny—and in Alexandria, knowledge was divine.

The Musaeum stood as a beacon to the world: a symbol of enlightened governance, cosmopolitan cooperation, and the noblest human aspiration—to understand the cosmos and ourselves.

The Nine Muses: Calliope (Epic Poetry), Clio (History), Erato (Lyric and Anacreontic Poetry), Euterpe (Music), Melpomene (Tragedy), Polyhymnia (Rhetoric and Hymns), Terpsichore (Dance), Thalia (Comedy) and Urania (Astronomy)

The Musaeum Grounds: A Sanctuary of Knowledge

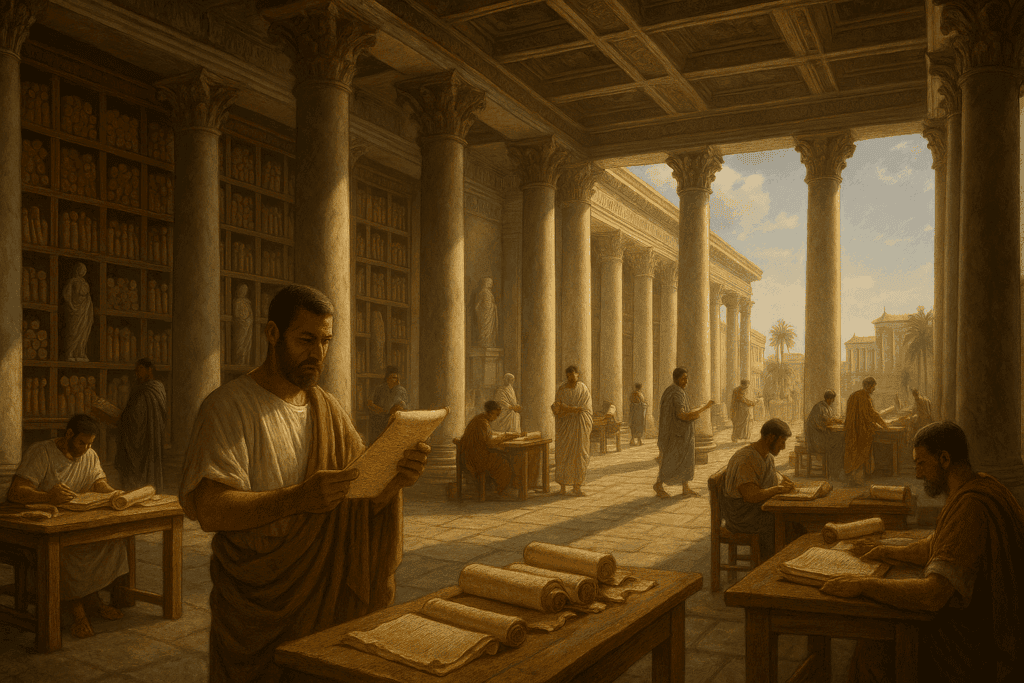

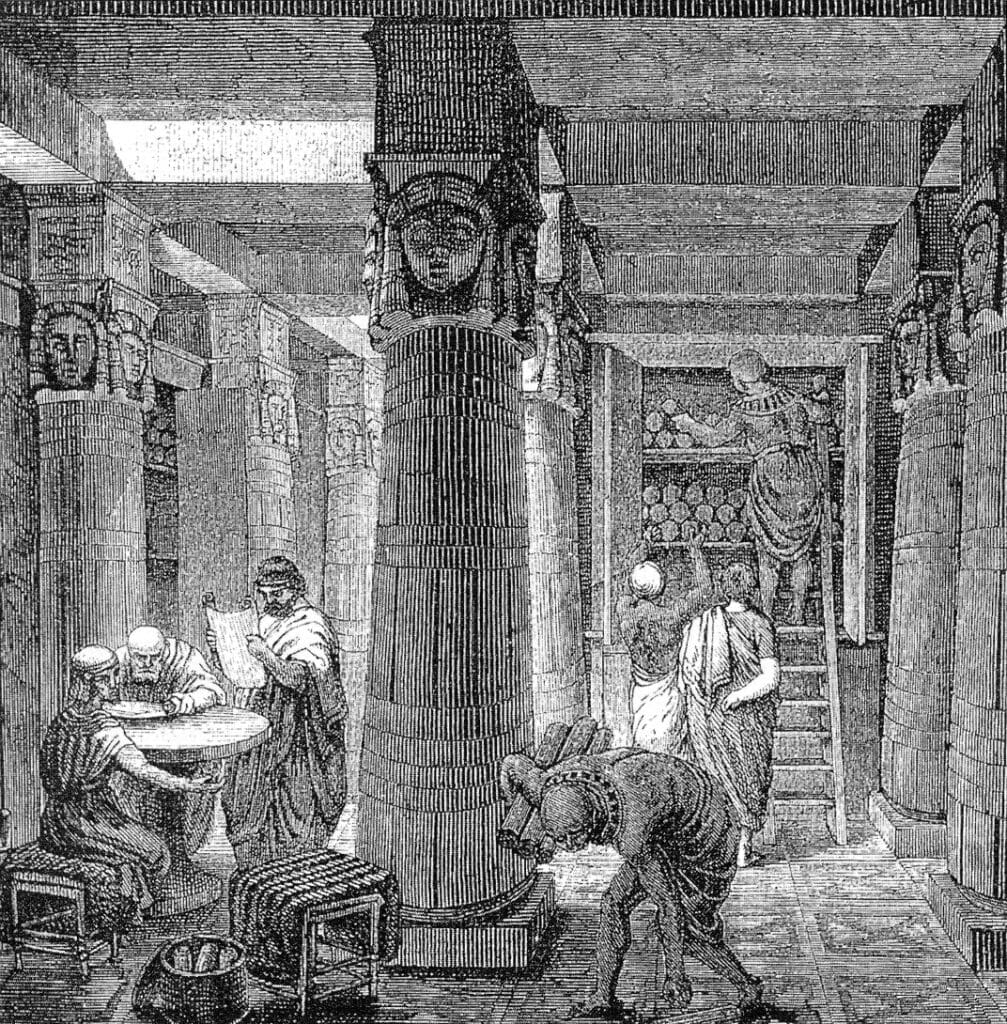

The physical structure of the Musaeum of Alexandria was as remarkable as its intellectual mission. According to the Greek geographer and historian Strabo (63 BCE – 24 CE), who visited the city in the first century CE, the Musaeum was an integral part of the royal palace complex, located in the prestigious Brucheion district, or royal quarter, of Alexandria.

“The Museum is a part of the palaces,” wrote Strabo in Geographia (XVII.1). “It has a public walk and a place furnished with seats, and a large hall, in which the men of learning, who belong to the Museum, take their common meal. This community possesses also property in common; and a priest, formerly appointed by the kings, but at present by Cæsar, presides over the Museum.”

This description offers a rare and evocative glimpse into the daily life of ancient scholars. The grounds were designed not merely for research and record-keeping, but to nurture a complete intellectual community—a place where ideas could be exchanged, tested, and refined through conversation, teaching, and shared meals.

The Musaeum included colonnaded walkways for reflection, gardens for contemplation, and a grand dining hall where scholars dined together. There were lecture halls, debate chambers, medical classrooms, and even a space outfitted for astronomical observation, hinting at the advanced scientific pursuits of its members.

In time, as the library’s holdings expanded beyond the capacity of its original structure, a second major repository—the Serapeum—was established under Ptolemy III Euergetes (r. 246–221 BCE). This satellite library was housed within a grand temple complex dedicated to Serapis, the Graeco-Egyptian god who represented the fusion of Hellenic and Egyptian religious traditions. The Serapeum stood in the Rhakotis district and functioned as both temple and library, reinforcing the sacred aura surrounding the quest for knowledge.

Within these halls stood statues of the twelve gods, and possibly the nine Muses—guardians of the arts and sciences. A 19th-century report by explorer Mimaut described nine statues holding scrolls, perhaps a tribute to the Muses themselves, each embodying a different discipline of human achievement.

The Musaeum’s Library, with its famed collection of papyrus scrolls, was the crown jewel of this sanctuary. It held the entire body of classical Greek literature, from Homer to Aristotle, as well as Egyptian priestly records, Homeric epics, the philosophical dialogues of Plato, and the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides.

The library also preserved and studied texts from beyond the Hellenic world, including works and fragments from Chaldean astrology, Zoroastrian theology, Hebrew scripture, and even Buddhist philosophy, brought west along ancient trade routes.

The Musaeum was, in every sense, a cosmopolitan temple of the intellect—a beacon of multicultural wisdom, scientific inquiry, and literary heritage. It stood as a testament to what is possible when human beings are given the freedom, support, and inspiration to ask the deepest questions and seek the noblest truths.

Two Rival Ancient Libraries: Pergamon and Antioch

As Alexandria’s reputation for scholarship flourished in the Hellenistic world, it soon met with competition from other cultural powerhouses rising across the eastern Mediterranean. Chief among these rivals were the cities of Pergamon in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) and Antioch in ancient Syria. Each developed their own centers of learning, seeking to rival—if not surpass—the prestige of Alexandria’s legendary Library.

The Library of Pergamon

Pergamon, perched atop a hill in the region of Mysia, became a formidable intellectual center under the Attalid Dynasty, whose lineage traced back to one of Alexander the Great’s generals, Lysimachus. In 282 BCE, Philetaerus, a military officer, seized the city and laid the foundation for Attalid rule. Later, under Attalus I, Pergamon was elevated to kingdom status, and its alliance shifted from Macedon to the rising power of Rome.

By the reign of Eumenes II (197–160 BCE), Pergamon had become a beacon of learning. Its royal library, second only to Alexandria, was said to contain over 200,000 scrolls. Unlike the Alexandrians, who used fragile papyrus, the librarians of Pergamon adopted a more durable material: parchment, made from treated animal skin. This innovation was so influential that the word “parchment” itself derives from the city’s name—pergamenum in Latin.

Though its influence waned after Attalus III bequeathed the city to the Roman Republic in 133 BCE, Pergamon’s library left an enduring mark on the world of ancient scholarship. Its ruins today stand as a solemn reminder of a once-thriving intellectual rival to Alexandria.

The Royal Library of Antioch

Further east, Antioch, capital of the Seleucid Empire, also rose to become a cultural giant. Founded by Seleucus I Nicator, another of Alexander’s generals, the city blossomed under Antiochus III the Great, who commissioned the establishment of a royal library around 221 BCE.

The king invited the brilliant Greek poet and scholar Euphorion of Chalcis to curate the collection and serve as its first chief librarian. Euphorion not only organized the library but also infused it with the spirit of Hellenistic learning, bringing together science, literature, and philosophy under one roof. During its height, the Royal Library of Antioch was considered by some to be even more prestigious than Pergamon, serving as the intellectual heart of the Seleucid court.

However, the library’s fate was tragic. In 363 CE, it was destroyed by fire under the Christian Roman Emperor Jovian, successor to Julian the Apostate. Julian, a pagan sympathizer, had converted the grand Traianeum temple into a repository of classical and “pagan” knowledge. Jovian, seeking to curry favor with Christian factions, reversed Julian’s reforms.

According to historical accounts, including Johannes Hahn’s Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt, Jovian’s destruction of the library—allegedly at the urging of his wife—was met with outrage by both pagans and Christians alike.

A temple filled with books and sacred scrolls was burned, and, according to legend, his concubines laughed as the flames rose, while horrified citizens stood powerless to stop the loss. The act, intended as a show of piety, was widely condemned as a barbaric assault on knowledge.

Librarians at the Library of Alexandria

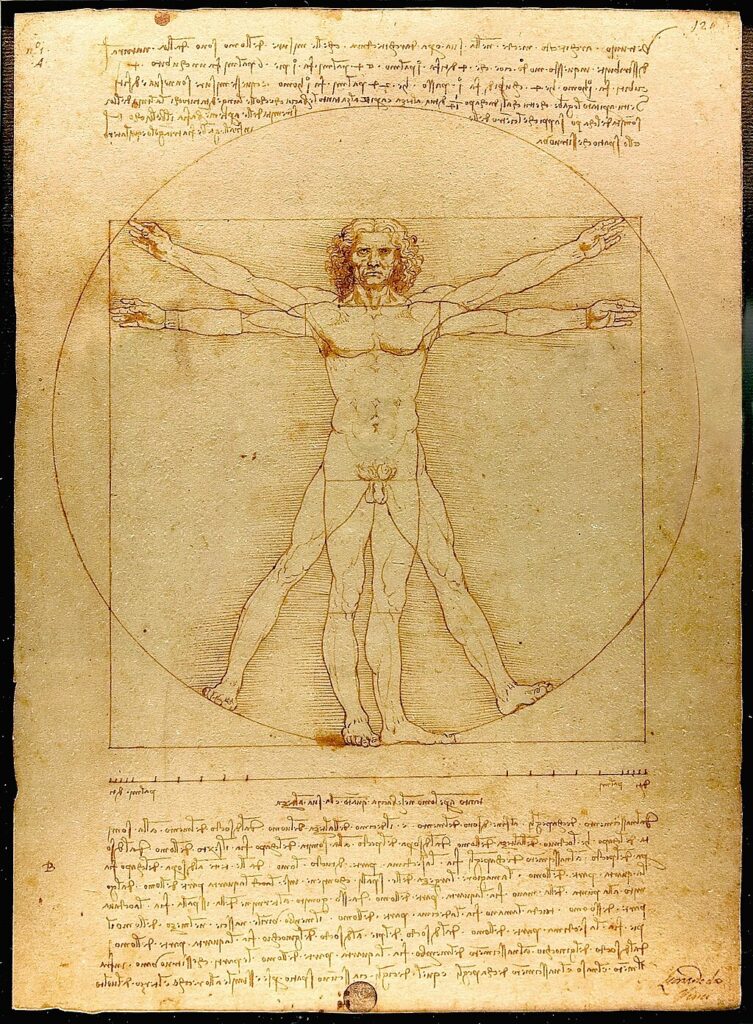

The scholars of the Musaeum of Alexandria—and the famed Library that was its heart—laid the intellectual foundation for many of the scientific disciplines we know today. Geometry, trigonometry, mechanics, engineering, round Earth theory, and even early heliocentric cosmology were explored, developed, and debated within its storied halls.

The Musaeum functioned much like a modern research university, offering a sanctuary for deep study, rigorous dialogue, and the cross-pollination of ideas from across the ancient world.

It was in this crucible of knowledge that the scientific method first took shape, and where the seeds of symbolic alchemy, natural philosophy, and cosmic speculation were sown—eventually flowering centuries later into the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Age of Reason, Freemasonry, and the Scientific Revolution itself.

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (c. 276–195 BCE)

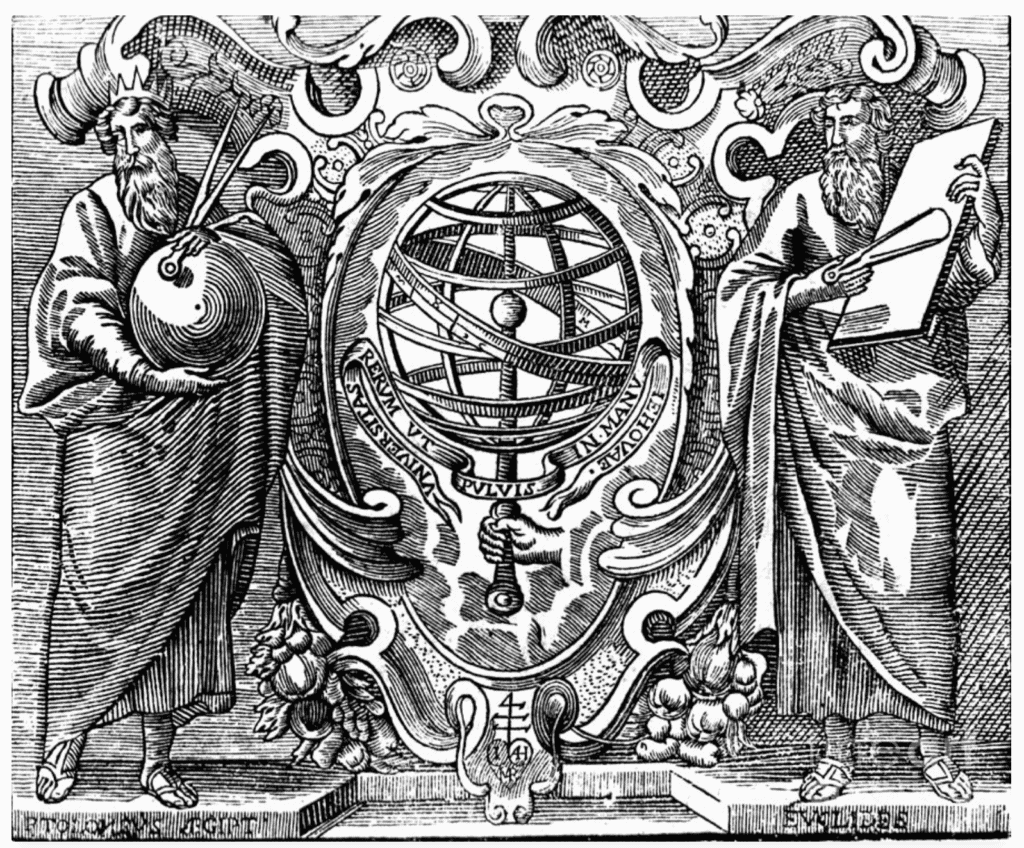

Among the most accomplished leaders of the Library was Eratosthenes, a polymath of rare genius and Chief Librarian during the 3rd century BCE. A mathematician, astronomer, geographer, music theorist, and philosopher, he is perhaps best remembered for being the first person to calculate the circumference of the Earth with remarkable accuracy, using nothing more than shadows, geometry, and simple observation.

He also:

- Calculated the tilt of Earth’s axis

- Estimated the distance between Earth and the Sun

- Invented the armillary sphere, an astronomical instrument used to model celestial motion

- Created the first map of the known world using a system of latitude and longitude

- Studied with Zeno of Citium, founder of Stoicism, and at Plato’s Academy in Athens

- Was a close friend of the renowned inventor Archimedes

Eratosthenes earned the affectionate nickname Beta (“the second best in everything”), because he was a master of so many fields that none could claim him as their own.

Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100–170 CE)

One of the most famous later scholars associated with Alexandria was Claudius Ptolemy, a Roman-era Greek mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, and geographer. Though he lived after the Library’s golden age, his work reflects the enduring legacy of its methods and data.

Ptolemy’s monumental work, the Almagest (Mathematical Treatise), became the authoritative model of the cosmos for over a thousand years. In it, he codified the geocentric model of the universe, drawing on centuries of astronomical records, including Babylonian data.

He also authored:

- The Geographia, a systematic treatise on cartography and geographic coordinates

- The Tetrabiblos, a foundational text on astrology, fusing observational astronomy with divinatory tradition

While his geocentric model would later be overturned by Copernicus, Ptolemy’s work represented a pinnacle of ancient astronomical reasoning, and his legacy as a synthesizer of knowledge remains unmatched.

Luminaries of the Library of Alexandria

The Library of Alexandria was not merely a repository of ancient knowledge—it was a thriving intellectual beacon that attracted some of the greatest minds of antiquity. Within its precincts, ideas flourished, disciplines intertwined, and revolutionary insights into nature, mathematics, medicine, astronomy, and philosophy were born. These pioneering scholars helped shape the very foundations of Western science, philosophy, and the liberal arts.

Demetrius of Phalerum (c. 350 – c. 280 BCE)

A student of Aristotle and former governor of Athens, Demetrius was instrumental in the early organization of the Musaeum and its library under Ptolemy I. He envisioned a repository that would collect, translate, and preserve all the world’s knowledge, a mission that would define Alexandria’s legacy. Though not a luminary in the traditional scientific sense, his role as a founder and organizer of knowledge systems was monumental.

Archimedes of Syracuse (c. 287 – 212 BCE)

Arguably the greatest mathematician of antiquity, Archimedes was also a legendary physicist, inventor, and astronomer. Though based in Sicily, his correspondence with Alexandria’s scholars and possible visits to the Musaeum deeply influenced his work.

He formulated principles of leverage, buoyancy (the Archimedean principle), and advanced concepts in calculus long before Newton. His inventions ranged from war machines to early pumps, and his mathematical insights were admired by thinkers from Cicero to Galileo.

Herophilos (335 – 280 BCE)

A pioneering physician and anatomist, Herophilos was the first known medical scientist to perform systematic dissections of human cadavers, establishing anatomy as a scientific field. In collaboration with Erasistratus, he founded a medical school in Alexandria and emphasized empirical observation and experimental method—principles that foreshadowed modern clinical science.

Euclid of Alexandria (c. 300 BCE)

Known as the “Father of Geometry”, Euclid authored Elements, one of the most influential works in the history of mathematics. Compiled and refined from earlier knowledge, Elements remained a standard textbook for over 2,000 years. Euclid’s clarity, deductive logic, and systematic methodology influenced not only mathematicians but also philosophers and scientists across the centuries.

Aristarchus of Samos (c. 310 – 230 BCE)

Centuries before Copernicus, Aristarchus boldly proposed a heliocentric model of the cosmos, placing the Sun at the center and the Earth in orbit around it. He correctly identified that the stars were distant suns, though his ideas were rejected at the time due to Aristotelian geocentrism. His legacy would later be vindicated during the Scientific Revolution.

Hipparchus of Nicaea (c. 190 – 120 BCE)

An astronomer and mathematician of profound influence, Hipparchus is credited with founding trigonometry, accurately calculating the length of the year, and discovering the precession of the equinoxes. He compiled one of the first comprehensive star catalogs, and developed celestial tools such as the astrolabe and armillary sphere, which would be used for centuries.

Timocharis and Aristyllus (3rd century BCE)

Contemporaries of Euclid, these astronomers compiled the first star catalog of the Western world. Their work on celestial coordinates laid the foundation for later developments in observational astronomy.

Callimachus (c. 310 – 240 BCE)

While never head librarian, Callimachus was a major figure at the library and the father of library science. He authored the Pinakes, the first known library catalog, which organized hundreds of thousands of scrolls by subject, author, and genre—a revolutionary system that set the standard for centuries.

Dionysius Thrax (170 – 90 BCE)

A distinguished grammarian and student of Aristarchus of Samothrace, Dionysius wrote The Art of Grammar, the first systematic manual of Greek grammar. His work laid the foundation for the study of language in both the East and West.

Hero (or Heron) of Alexandria (c. 10 – 70 CE)

An ingenious mathematician and engineer, Hero authored numerous treatises on pneumatics, mechanics, and automata. His inventions included the first steam engine (the aeolipile), the first vending machine, and early programmable devices. His works reveal a deep understanding of physics far ahead of his time.

Theon of Alexandria (c. 335 – 405 CE)

A philosopher and mathematician, Theon is remembered for his commentaries on Ptolemy’s Almagest and for preserving key Classical texts. He also edited and published works that would later inform early medieval astronomy and mathematics.

Hypatia of Alexandria (c. 350 – 415 CE)

The daughter of Theon, Hypatia was a brilliant philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer—widely considered the first notable female scientist in Western history.

As head of the Neoplatonic school in Alexandria, she taught Plotinian philosophy and science. A respected public intellectual, she was tragically murdered by a mob in a moment of political and religious turmoil, marking the symbolic end of Alexandria’s golden age.

The Destruction of the Library of Alexandria

The fall of the Great Library of Alexandria remains one of history’s most tragic losses to human knowledge. Despite its fame, the facts surrounding its destruction are shrouded in uncertainty and conflicting historical accounts. Rather than a single catastrophic event, historians now believe that the Library met its end gradually—ravaged by a series of calamities over centuries.

A Legacy of Fire and Conflict

Various ancient sources point to multiple instances in which the Library suffered damage:

- In 48 BCE, during Julius Caesar’s siege of Alexandria, fire from the Roman fleet is said to have spread to the docks and adjacent buildings, potentially destroying part of the Library’s holdings.

- In 273 CE, civil conflict under Emperor Aurelian during the reconquest of the city may have resulted in further destruction of the Library or its surroundings.

- A secondary repository of knowledge, the Serapeum—the Temple of Serapis—was also home to a large portion of the Library’s holdings. It, too, would face a similar fate.

By the time of the late 4th century, the intellectual flame of Alexandria flickered on borrowed time. The Library, once the greatest repository of classical knowledge in the ancient world, had already suffered repeated blows. Yet it was the rising tide of religious and political change that would deliver the final destruction.

The Edict of Theodosius I and the Christian Uprising

In 391 CE, the Roman Emperor Theodosius I, a devout Christian, issued a series of edicts banning pagan practices and temples. This marked a decisive turning point for Alexandria. With imperial backing, a wave of Christian zeal swept through the city.

It was under the direction of Bishop Theophilus, and later supported by his nephew Cyril, that a Christian mob attacked the Serapeum, razing it to the ground. This act was not merely the destruction of a religious temple—it was the symbolic dismantling of a centuries-old tradition of Hellenistic science, philosophy, and religious pluralism.

Though the original Royal Library may have already been in decline, the Serapeum—which served as the “daughter library”—was the last major remnant of the Musaeum’s intellectual heritage. With its destruction, what remained of that golden age of learning was cast into ruin.

The Fall of Hypatia (Trigger Warning)

The death of Hypatia in 415 CE, brutally murdered by a Christian mob (with broken roof tiles and seashells), further signaled the end of Alexandrian intellectual life. As a prominent Neoplatonist philosopher and astronomer, Hypatia had inherited the legacy of Plato, Aristotle, and Ptolemy. Her assassination was not only a personal tragedy but also a symbol of the growing hostility toward secular, scientific, and philosophical inquiry.

The Aftermath

The loss of the Library of Alexandria did not just mean the disappearance of thousands of scrolls—it meant the disruption of a tradition. Works of mathematics, astronomy, engineering, medicine, botany, history, and philosophy—many of which were not copied elsewhere—vanished into the ashes. It would take over a thousand years before science in the Western world could regain comparable momentum.

In time, other cultures—particularly in the Islamic Golden Age—would translate, preserve, and build upon fragments of Alexandrian learning. But the original spirit of the Musaeum—the dream of a global academy of knowledge without borders—had died.

Legacy

The destruction of the Library of Alexandria stands as a solemn reminder of the fragility of knowledge in the face of ignorance, ideology, and intolerance. It also teaches us that wisdom must not only be preserved, but protected and renewed.

Today, in the digital age, where the sum of human knowledge can fit in our pockets, we are more empowered than ever to honor that ancient dream: a world united not by conquest, but by curiosity, reason, and learning.

Let the memory of the Musaeum and its scholars serve not merely as an elegy—but as a call to action for a new renaissance.

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina: A Modern Beacon of Knowledge

In a symbolic act of remembrance and renewal, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina was inaugurated in 2002 on the shores of the Mediterranean, near the presumed site of the ancient library.

Designed by the Norwegian architecture firm Snøhetta and supported by UNESCO and the Egyptian government, this modern library aspires to revive the spirit of the lost Musaeum—a home for learning, cross-cultural dialogue, and the preservation of knowledge.

The Bibliotheca is more than a library—it is a cultural and scientific complex. It houses millions of books, state-of-the-art research centers, museums, art galleries, and a planetarium. It welcomes scholars and the public alike, offering open access to resources in the spirit of universal human inquiry.

Though it cannot restore what was lost, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina serves as a living monument to humanity’s enduring quest for understanding, and a powerful reminder that knowledge must be preserved, shared, and defended.

Its very existence speaks to a global recognition that ideas—once silenced by fire or fear—must now be protected by institutions of openness, cooperation, and truth.

Modern Reflections: The Enduring Legacy of the Library of Alexandria

The ancient Library and Musaeum of Alexandria were not merely halls of books and learning—they were living symbols of an intellectual civilization committed to the pursuit of wisdom beyond borders.

For nearly seven centuries, Alexandria thrived as the beacon of knowledge for the ancient world, its scholars preserving and expanding the sciences, arts, and philosophies of every great civilization it touched—Egyptian, Greek, Persian, Babylonian, Indian, and beyond.

And yet, in 391 CE, the light was snuffed out.

Fueled by religious zeal and imperial authority, Christian mobs—led by Patriarch Theophilus and sanctioned by Emperor Theodosius I—descended upon Alexandria’s Serapeum, the last stronghold of the old learning. They employed Roman military tactics to storm the sanctuary, sack its treasures, and destroy what they could not comprehend.

While the main library’s fate is uncertain—some claim it had already been diminished by earlier conflicts or its texts relocated—the symbolism of the destruction remains stark: a deliberate war on knowledge, pluralism, and intellectual freedom.

Eyewitnesses recount how the stone foundations were all that remained. The scrolls, monuments, and memory of an age of reason vanished into the smoke. And with it, the ancient world turned a page—entering the long night of the Dark Ages, in which critical thought and scientific progress were often suppressed by authoritarian and theocratic rule.

The Knowledge That Survived

Yet knowledge, like fire, is hard to kill completely.

Fragments of Alexandria’s legacy were carried east to the Imperial Library of Constantinople, the Academy of Gondishapur in Persia, and the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, where Muslim scholars translated and preserved much of Greek and Roman science.

From there, during the Islamic Golden Age, knowledge was rediscovered by Europe through the Reconquista in Spain, contributing to the rise of European universities, and ultimately, to the Renaissance, Enlightenment, and Scientific Revolution.

Still, the loss remains incalculable. Lost works by Aristotle, Sophocles, and unknown thinkers of every tradition may have held answers to questions we still ponder today. What might the world have looked like if Alexandria had endured?

Building the New Alexandria

In 2002, the dream of Alexandria was rekindled with the opening of the Bibliotheca Alexandrina—a breathtaking modern library and cultural center built near the site of the ancient Musaeum.

It serves as a powerful memorial to that lost world of learning and a promise that such loss will not happen again. Today, its digital collections, multilingual resources, and educational programs connect people across cultures in the spirit of universal human curiosity.

Yet the mission is broader than one building.

Modern institutions such as UNESCO, the Internet Archive, and global digital libraries now fight a new war—not against fire, but against forgetting. In a world of misinformation, ideological division, and rising anti-intellectualism, the struggle to preserve, protect, and democratize knowledge is more urgent than ever.

One such modern initiative is Science Abbey, a spiritual and scientific movement devoted to building a “monastery without walls”—a decentralized, global academy where reason, humanism, and scientific wisdom are cultivated. Rooted in the same values that animated the Musaeum, it aims to redefine faith not as blind belief, but as trust in mindfulness, compassion, critical thinking, and the scientific method.

A New Age of Illumination

What Alexandria once symbolized, the world must reclaim: a civilization dedicated to knowledge without borders, to curiosity without dogma, and to truth without fear.

Let the ruins of the Serapeum, and the haunting silence of the lost Library, remind us that learning must be protected, not just preserved. Let us not wait for another light to be extinguished before we realize what we’ve lost.

In the modern Alexandria of today—on the internet, in universities, libraries, and the living memory of human progress—we are the stewards of the muses. Let us build wisely.

As we look to the future, Science Abbey emerges as a spiritual and intellectual successor to the Musaeum of Alexandria—a 21st-century sanctuary for wisdom, rooted not in stone but in shared values, open access, and collective responsibility.

Where the ancient library sought to gather the knowledge of the world, Science Abbey seeks to awaken the mind of the world—empowering individuals across borders with tools of critical thinking, scientific literacy, ethical reasoning, and secular spirituality.

In this way, we honor the past not with nostalgia alone, but with action: creating a new age of illumination, where no library burns and no mind is left in darkness.