Inside Monasticism Series Part 6

Introduction: The Call of the Desert

At the edge of civilization—beyond the noise of cities, the weight of politics, and the rhythms of ordinary life—a voice once whispered through the stillness of the desert: Leave everything behind. Come and be with God alone.

So began one of the most radical spiritual movements in human history.

Christian monasticism was not born in cathedrals or universities. It emerged in sand-swept caves, in stone huts beneath olive trees, in the whispered silence of the early centuries after Christ. The first monks were not bishops or scholars. They were seekers—men and women who longed to know their God not through ideas or dogma, but through silence, surrender, and solitude.

These early ascetics—later called the Desert Fathers and Mothers—fled to the wilderness not to escape the world, but to save it. They believed the true transformation of humanity begins not with power or politics, but with the soul purified by prayer.

Monasticism became the beating heart of Christian spirituality. From the deserts of Egypt to the forests of Ireland, from Mount Athos to the French abbeys of Cluny and Cîteaux, monks and nuns shaped the memory of the Christian world. Their lives of devotion preserved sacred texts, cultivated music, grew food, healed the sick, sheltered the poor, and prayed—unceasingly—for the world.

To be a monk, said St. Benedict, was to live as if you would die every day.

And yet, monasticism is not a story of death, but of deeper life. It is a tale of humble human beings seeking the divine in the fabric of every breath, every task, every moment.

In an age overwhelmed by distraction, speed, and noise, the ancient monastic vision is rising again. Across the world, in abbeys and hermitages, in urban monasteries and silent chapels, in homes and hearts, the cloistered life calls not just monks and nuns—but anyone who dares to seek the sacred in stillness.

This article traces the path of Christian monasticism from its roots in the desert to its enduring presence today. Along the way, we will meet prophets and mystics, builders and scribes, rule-makers and rule-breakers. We will hear the wisdom of those who gave up everything not out of despair, but out of a holy desire for the one thing that never passes away.

Welcome to a world of silence and song, of cloisters and callings. Welcome to the sacred life.

Early Western Monasticism

Long before the rise of Christian monasticism, the spiritual climate of the ancient world was already fertile with religious devotion, ascetic practices, and mystical traditions. In ancient Egypt, religious life revolved around deep-rooted beliefs in divine law (ma’at), righteousness, healing, magic, resurrection, and the afterlife.

Egyptians practiced these traditions through worship, prayer, sacrifice, and sacred rituals conducted by a priesthood that included both men and women. The Egyptian worldview, rich in its polytheism and evolving monotheistic ideas, had a significant influence on Hebrew, Greco-Roman, and early Christian religion.

Though historical evidence is sparse, it is likely that Egyptian hermits committed to the native religion withdrew into the desert long before Christian ascetics emerged. However, the first clearly documented forms of Western monasticism appear not in pagan Egypt, but among two unique Jewish sects: the Essenes and the Therapeutae.

The Essenes, a Jewish ascetic group contemporary with Jesus of Nazareth, are perhaps best known today for their connection to the Dead Sea Scrolls. They lived in strict communities, practiced celibacy, observed communal living, and devoted themselves to scripture and ritual purity. Their lifestyle prefigured many elements of later Christian monasticism.

A parallel tradition is described by the Jewish-Hellenistic philosopher Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE – 50 CE), who offers the earliest known Western reference to monastics in his work On the Contemplative Life. In it, Philo details the life of the Therapeutae, a contemplative and mystical Jewish group who lived around Lake Mareotis near Alexandria, Egypt.

Unlike the practical lifestyle of the Essenes, the Therapeutae pursued speculative philosophy, meditation, and communal worship while leading celibate, ascetic lives in isolated settings. Philo explains that such contemplative individuals could be found not only in Egypt but also “in many places… for both Greece and barbarian countries want to enjoy whatever is perfectly good.”

These proto-monastic groups flourished in a religious landscape shaped not only by Judaism but also by the mystery religions of antiquity—spiritual cults that emphasized secret knowledge, rites of initiation, and mystical union with the divine. These included the Eleusinian, Dionysian, and Orphic Mysteries, the Cult of Isis, and the rites of Mithras and Sol Invictus. These traditions also paved the way for the development of esoteric and mystical elements within early Christianity.

The language of early Christianity reflects this inheritance. The Greek word mysterion (μυστήριον), used in the New Testament 27 times, referred not to “mystery” in the modern sense, but to hidden divine truths—spiritual realities accessible only through faith and revelation, not reason alone. Central Christian doctrines such as the Trinity, the Incarnation, and the Resurrection were all considered holy mysteries.

Thus, by the time Christian monasticism began to flourish in the Egyptian desert in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE—with figures such as St. Anthony the Great and St. Pachomius—it drew upon a rich tapestry of earlier Jewish, Egyptian, Greek, and Roman spiritual traditions. These roots helped to shape what would become one of the most enduring and transformative institutions in Christian history.

The Earliest Western Monastics: The Essenes and the Therapeutae

Before Christian monasticism emerged, two Jewish groups—the Essenes and the Therapeutae—laid the early groundwork for communal spiritual living in the Western tradition.

The Essenes

Active from the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century CE, the Essenes were a Jewish sect known for their austere, disciplined lifestyle. They lived in isolated, celibate, and tightly organized communities near the Dead Sea—most famously at Qumran, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered.

The Essenes practiced ritual purity, communal property, regular prayer, and strict adherence to the Torah. Their way of life has often been compared to later Christian cenobitic monasticism.

The Therapeutae

Described by the philosopher Philo of Alexandria, the Therapeutae were a Jewish ascetic community living near Lake Mareotis in Egypt, around the same period. The name may derive from a root meaning both “healer” and “worshiper.”

They combined study, contemplation, fasting, and communal meals with a highly spiritual life devoted to Scripture and prayer. Men and women lived in neighboring quarters in chastity and solitude during the week, gathering only on the Sabbath.

Together, these groups represent some of the earliest examples of structured religious communal life in the West—precursors to Christian monasticism that would later develop in the deserts of Egypt and beyond.

Proto-Monasticism, Alexandria, and the Imperial Shift Toward Monasticism

Christian monasticism found fertile ground in Egypt—a land with deep religious roots stretching back to the dawn of civilization. As early as 42 CE, Christian tradition holds that Saint Mark the Evangelist brought the gospel to Alexandria, laying the foundations for one of the most vibrant early Christian communities. By the third century, the Church of Alexandria had become one of the four great Apostolic Sees, second in prominence only to Rome.

Alexandria soon emerged as a spiritual and intellectual hub, where theological innovation and ascetic ideals flourished. Thinkers like Clement of Alexandria and Origen emphasized the mystical union with God, healing of both body and soul, and a holistic ascetical theology that deeply shaped emerging monastic ideals. Clement famously declared, “Jesus heals the whole human person, body and soul,” reflecting an ideal that would resonate through later Christian mysticism.

Even before Christian monasticism took recognizable shape, ascetic tendencies were present in Jewish and early Christian circles. Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE – 50 CE) describes the Therapeutae, a group of Jewish contemplatives near Lake Mareotis, as living lives of prayer, celibacy, and simplicity—hallmarks of what would later be called monastic life.

Alongside them were the Essenes, a Jewish sect known for their disciplined communal life and strict moral code. Both groups represent a kind of proto-monasticism—intentional, ascetic communities that preceded Christian monasticism but foreshadowed its development.

In the 3rd century, the Syriac Christian movement known as the “Sons of the Covenant” practiced a form of structured asceticism that also mirrors early monasticism, including vows of celibacy and voluntary poverty.

Saint Anthony and the Rise of the Desert Fathers

Christian monasticism as a distinct form of life began with Saint Anthony the Great (c. 251–356 CE), often called the Father of Monasticism. Inspired by Jesus’ words, “If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast… and come and follow me” (Matthew 19:21), Anthony gave away his family’s wealth, entrusted his sister to a Christian community, and departed for the Nitrian Desert near Alexandria.

There, he lived a life of intense solitude, prayer, and asceticism, eventually drawing followers who gathered around his cell, forming the basis for what would become the Monastery of Saint Anthony, the oldest continuously operating Christian monastery in the world.

This transition—from solitary hermitage to a community of like-minded seekers—marks the beginning of organized monastic life in the Christian tradition. Anthony’s cave hermitage, high above the desert floor, is still accessible by a winding stairway, symbolizing the spiritual ascent sought by those who followed him.

Among those inspired by Anthony was Saint Ammon, another pioneer of desert hermitry, and later the monastic leader Saint Macarius of Alexandria, who presided over thousands of monks in the Egyptian desert.

The Imperial Shift: Constantine’s Role

Monasticism gained momentum after the conversion of Emperor Constantine the Great (r. 306–337). Once persecuted, Christianity became increasingly accepted and eventually favored by the state. With the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, Constantine legalized Christianity, ending centuries of official persecution. As Christianity rose in prestige, many ascetics, once scattered or persecuted, found a new context for spiritual withdrawal.

Constantine’s reign marked a legal and social turning point. Monasteries began receiving imperial support and protection. Wealthy patrons, including emperors and nobles, endowed monasteries with land and resources. Monasticism, once a marginal path, now had legal recognition and a burgeoning infrastructure.

Yet the spirit of renunciation remained strong, especially among the Desert Fathers, who withdrew from the world not only to escape persecution, but also to avoid the temptations of power and comfort now associated with the institutional Church.

Roots in the Wilderness: The Desert Fathers and Mothers

Long before monasteries rose with stone walls and stained glass, Christian monasticism was born in the silence of the desert.

It began in the third and fourth centuries CE, as the Roman Empire transitioned to Christianity and the faith became increasingly entangled with power and public life. While the Church gained protection and prestige, a few radical souls saw this as a dangerous compromise. They longed for a purer, unmediated form of Christian life—one that echoed the radical call of Jesus: “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me.” (Matthew 16:24)

So they fled—not out of fear, but out of longing.

The First Monks

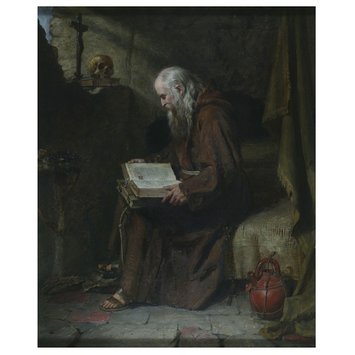

The first known Christian monk was St. Anthony the Great (c. 251–356 CE), a wealthy Egyptian who sold all his possessions and moved to the Eastern desert to live alone in prayer and fasting. His fame spread quickly. Disciples followed him into the wilderness, forming loose-knit communities of hermits. Soon, the desert was filled with seekers.

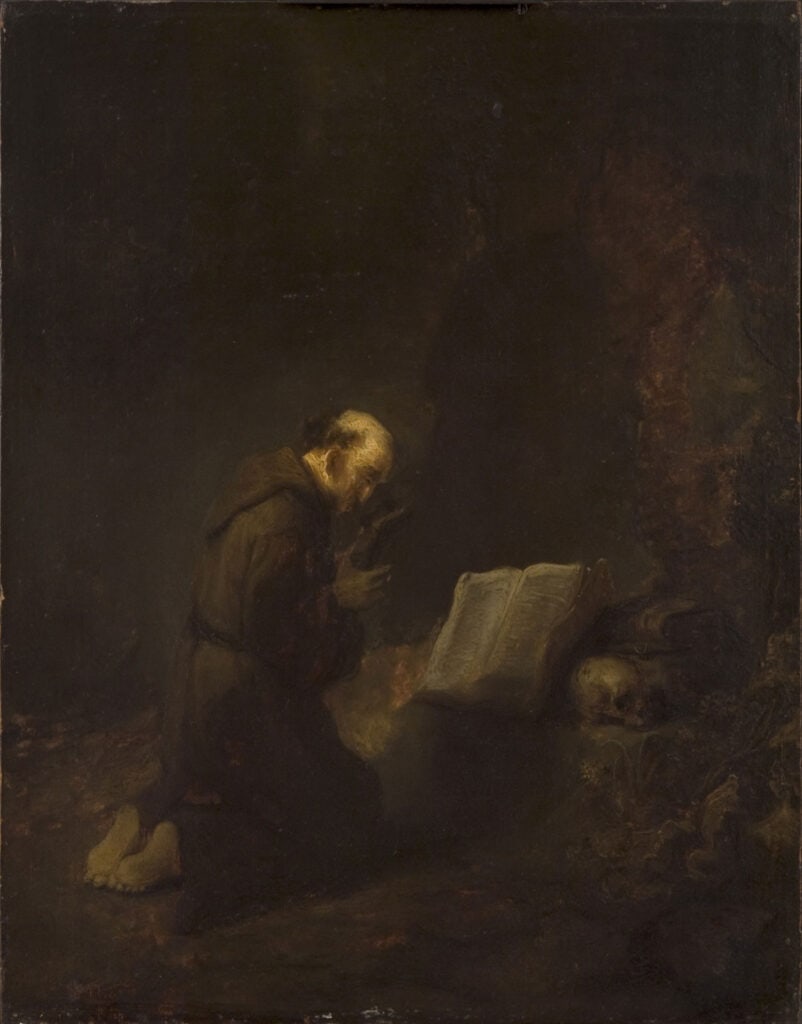

They lived in caves, huts, or abandoned ruins. They practiced extreme austerity—eating sparsely, sleeping little, and praying constantly. They sought to conquer the ego and quiet the passions through solitude, silence, and labor. Many wrote of demonic temptations, spiritual visions, and mystical encounters.

These spiritual pioneers became known as the Desert Fathers (Abbas) and Desert Mothers (Ammas). Though they lived far from the cities, their teachings traveled across the Christian world. Their sayings—preserved in texts like The Sayings of the Desert Fathers—form one of the earliest and most enduring voices of Christian spiritual wisdom.

An Inner Martyrdom

To the Desert Fathers and Mothers, monasticism was a form of martyrdom—not through blood, but through the death of the ego. Their life was a long obedience, a purification of the heart. They practiced hesychia—the inner stillness sought through prayer, silence, and mindfulness of God.

They didn’t seek perfection. They sought humility.

One famous saying tells of a novice asking an elder monk, “What do you do in the monastery?” The elder replied: “We fall down and get up. We fall down and get up.”

Their witness formed the foundation of the Christian mystical tradition. In their lives, we glimpse a faith not rooted in rules or rewards, but in the raw and radiant pursuit of divine presence.

Mendicant and Cenobitic Orders: Mobility and Community in Monastic Life

Within the rich tapestry of Christian monasticism, two distinct yet sometimes overlapping forms of religious life have shaped the spiritual and social fabric of the Church: mendicant orders and cenobitic orders. While cenobitism emphasizes communal, stable life within a monastery, mendicancy implies movement, poverty, and public ministry. Remarkably, some religious communities have managed to embody both dimensions, integrating prayerful communal life with itinerant evangelism.

Cenobitic Monasticism: Life in Community

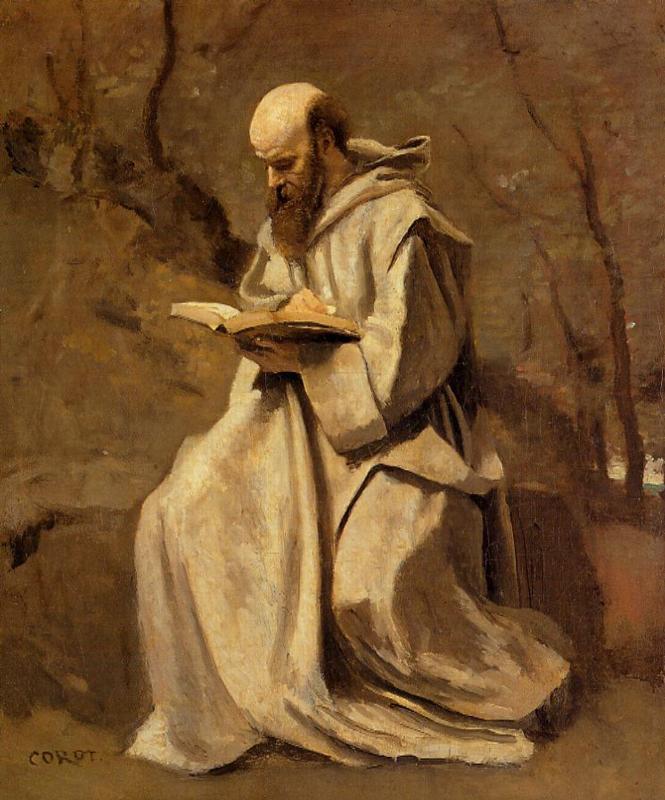

The cenobitic model, from the Greek koinos bios (common life), was solidified in Christian tradition through early pioneers like Pachomius, Basil the Great, and Benedict of Nursia. Cenobitic monks live under a rule, in shared obedience to an abbot or prior, dedicating their lives to prayer, work, study, and mutual support. The Rule of St. Benedict, written in the 6th century, became the gold standard of Western cenobitic monasticism, influencing monastic life across medieval Europe and beyond.

Cenobitic monasteries were often self-sufficient, rural communities centered on daily rhythms of prayer, agriculture, craftsmanship, and learning. These monasteries preserved not only theological wisdom but also classical literature, science, and medicine through the so-called “Dark Ages.” However, as the centuries wore on, their increasing accumulation of wealth, land, and influence distanced them from the radical poverty of the Gospel—and from the changing needs of a rapidly urbanizing society.

Mendicant Orders: Poverty and Preaching in Motion

The mendicant orders, by contrast, emerged in the 13th century as a powerful response to both internal Church corruption and external social transformation. The term mendicant, meaning “begging” or “open-handed,” refers to their radical commitment to evangelical poverty, renunciation of property, and reliance on charity. Rather than withdrawing from society, friars went into the heart of it—ministering in towns and cities, preaching in marketplaces, teaching at universities, and tending to the spiritual and material needs of the laity.

Unlike monks, who were traditionally cloistered and stationary, friars were itinerant preachers. They lived in friaries rather than monasteries and took vows of poverty and obedience, but their structure differed: rather than autonomous houses, mendicant orders were governed by a centralized leadership and subdivided into provinces. This allowed for greater flexibility and mobility, as friars could be deployed wherever the need was greatest.

The four great mendicant orders officially recognized by the Catholic Church were:

- Franciscans (Order of Friars Minor), founded by St. Francis of Assisi, dedicated to poverty, humility, and care for the poor and sick.

- Dominicans (Order of Preachers), founded by St. Dominic, focused on intellectual formation and combating heresy through preaching and education.

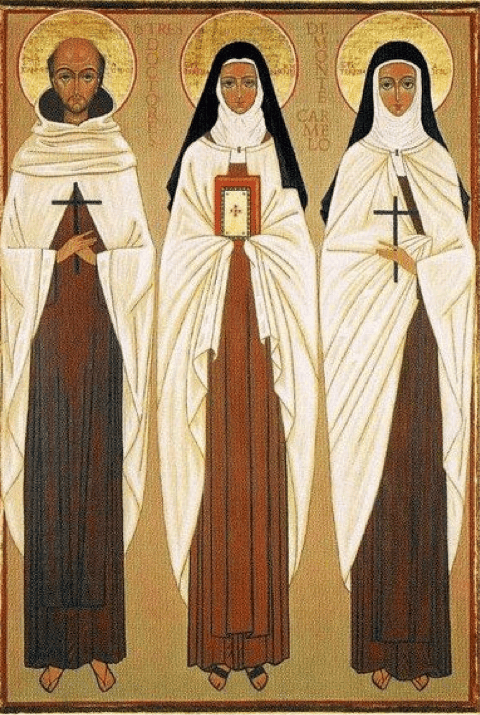

- Carmelites, originally hermits on Mount Carmel, who adapted to mendicant life in Europe while maintaining a contemplative core.

- Augustinians, who followed the Rule of St. Augustine and emphasized community life combined with active pastoral ministry.

- Servites (Servants of Mary), added later, focused on Marian devotion and service.

In all of these, a hybrid model emerged: friars lived in cenobitic communities but practiced a mendicant lifestyle, walking the cities, begging for food, and engaging in public ministry. This dual form was not unique to Christianity—parallel models can be found in Buddhist and Hindu traditions. For example, in Theravāda Buddhism, monks venture out in the early morning to collect alms but return to their monasteries to eat and study in a communal setting, blending mendicancy with cenobitism.

A Response to Urbanization and Reform

The rise of urban centers in medieval Europe had left the rural Benedictine model increasingly out of touch with the needs of the people. At the same time, a new class of educated laypeople was demanding deeper theological sophistication and pastoral presence than the overworked or undereducated parish clergy could provide. The mendicants were the Church’s answer—spiritual professionals who were mobile, articulate, and deeply devoted.

Friars were often trained at newly established universities—Oxford, Paris, Bologna—and held theological chairs. Thinkers like Thomas Aquinas (a Dominican) and Bonaventure (a Franciscan) were instrumental in synthesizing theology and philosophy, faith and reason.

Moreover, in the wake of the Crusades and a growing awareness of the suffering and moral failures of the institutional Church, lay revival movements had begun to arise, often in quasi-eremitic or penitential forms. The friars—especially with the backing of the papacy—offered a constructive, orthodox path for spiritual renewal.

Mendicancy and Monastic Identity

Although technically friars are not monks, the spiritual goals of both mendicant and cenobitic orders are closely aligned: to seek God through poverty, obedience, and service. In practice, many communities blurred the lines. Some mendicant orders adopted communal rhythms of prayer and study, while some monastic orders adopted missionary outreach and public preaching.

The dynamic tension between withdrawal and engagement, contemplation and action, solitude and service, continues to inform Christian monasticism to this day. Whether walking barefoot through a medieval market or quietly chanting psalms in the monastery chapel, the monk and the friar seek the same mystery—the God who meets us both in the wilderness and in the world.

The Superior General

The Superior General is the highest-ranking leader of a religious order or congregation, especially in those that are international or widely distributed. Unlike an abbot, whose authority is usually confined to a single monastery, the Superior General oversees the entire order across all its provinces, houses, or regions, ensuring uniformity, fidelity to the rule, and accountability among leaders. The Superior General is elected by representatives of the order, often for a fixed term, and holds authority similar to a governing head or presiding elder within the broader organizational structure of the order.

What Is an Abbot?

An abbot is the spiritual and administrative leader of a Christian monastic community, particularly in cenobitic (communal) monasteries. The word abbot is derived from the Aramaic abba, meaning “father,” and reflects the paternal role of the abbot as both a guide and caretaker of the monastic brothers under his charge.

In the Benedictine tradition, the abbot is elected by the monks of the monastery and holds a position of lifelong authority, unless removed for cause. According to the Rule of St. Benedict, the abbot is to lead by example, more like a shepherd than a ruler—firm but compassionate, instructing the community in virtue, discipline, and the pursuit of holiness.

The abbot’s duties include:

- Presiding over the Divine Office (the daily prayer schedule)

- Overseeing the material and spiritual well-being of the monastery

- Enforcing the rule of the order (e.g., the Rule of St. Benedict)

- Representing the monastery in dealings with the Church hierarchy and the wider world

In female monastic communities, the equivalent role is called an abbess.

The abbot stands as a symbol of stability, order, and spiritual fatherhood, embodying the ideal of the wise elder in the Christian monastic tradition.

Prior

A prior is the second-in-command in a monastic community, serving directly under the abbot. In some orders or smaller houses, the prior may be the superior if there is no abbot. Priors assist in the daily governance of the monastery, ensuring that the Rule is followed and that the spiritual and practical disciplines of the monastic life are maintained. The term can also refer to the head of a priory, a monastic community that is smaller or subordinate to an abbey.

Novice

A novice is a beginner or candidate in a monastic community who has entered a period of formation and discernment before taking vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. This stage, known as the novitiate, typically lasts one to two years and involves rigorous training in the monastic lifestyle, prayer, work, and the Rule of the order. Novices wear distinctive habits (often simpler) and live under close supervision by the novice master or mistress. They are not yet full members of the order and can leave—or be dismissed—without formal process.

Here’s a clear visual hierarchy to show how these roles—Superior General, Abbot, Prior, and Novice—typically relate to one another within the structure of a Christian monastic order:

Monastic Hierarchy Overview

Monastic Hierarchy Overview

SUPERIOR GENERAL

(Leads the entire religious order worldwide)

│

┌─────────┴─────────┐

│ │

PROVINCIALS* OTHER OFFICIALS

(Oversee regional (e.g., General Council,

divisions called Secretary General)

Provinces)

▼

ABBOT

(Head of an individual abbey or monastery)

▼

PRIOR

(Second-in-command at the local monastery;

assists or replaces the abbot as needed)

▼

MONKS / NUNS

(Professed members of the community)

▼

NOVICE

(Newcomer undergoing training before vows)

*Note: Some orders have Provincials or Regional Superiors between the Superior General and local abbots/priors depending on size and organization.

Oblate and Oblation

Oblate

An oblate (from Latin oblatus, meaning “offered”) is a person who is dedicated to God and affiliated with a monastic community, without taking full monastic vows. Oblates often live in the secular world—outside the monastery—but commit to living according to the spiritual values and rule (such as the Rule of St. Benedict) of the monastic order they are attached to.

There are two kinds of oblates:

- Monastic Oblates: Individuals who live in the world but are spiritually united to a monastery. They may adopt regular prayer times, acts of service, and study.

- Child Oblates (historically): In earlier centuries, children could be offered by their parents to be raised and educated in a monastery, with the expectation that they would eventually become monks or nuns. This practice has largely faded.

Oblation

Oblation is the act of offering or presenting something to God. In a monastic context, it most often refers to the spiritual offering of oneself to God—an act symbolized during religious ceremonies. The term also applies more broadly to offerings made during the Mass or Divine Liturgy, such as bread, wine, or monetary gifts.

In essence, to be an oblate is to live as an offering, and oblation is the sacred act of making that offering.

The Rise of Monastic Communities: Pachomius, Basil, and Benedict

As the passion for the eremitic life spread across the Christian world, it became clear that not all seekers were called to solitary wilderness. Some required structure, guidance, and support. From this realization emerged a new form of monasticism: cenobitic life—monasticism in community.

St. Pachomius: The First Monastic Rule

In the early fourth century, St. Pachomius (c. 292–348 CE), a former soldier in Upper Egypt, envisioned a way for monks to live not as hermits, but together under a common rule. Around 320 CE, he founded the first true Christian monastery at Tabennisi along the Nile.

His communities balanced prayer, work, and study. Monks slept in shared quarters, followed fixed hours for prayer (the Divine Office), ate together, and labored in gardens, kitchens, and scriptoria. All possessions were held in common.

Pachomius’s Rule, or monastic guideline, is the earliest known, and his model of communal monasticism spread rapidly across Egypt and the Mediterranean. His approach provided a rhythm of life that united spiritual growth with practical order—a legacy that deeply influenced future monastic systems.

St. Basil the Great: Eastern Monastic Vision

In Cappadocia (modern-day Turkey), St. Basil the Great (c. 330–379 CE) built upon Pachomius’s vision. A brilliant theologian and bishop, Basil crafted a Rule that emphasized humility, liturgical life, and charity. Unlike the more austere desert traditions, Basil’s communities served the sick and poor. His monks were scholars, caretakers, and citizens—engaged, not withdrawn.

Basil’s Rule became the foundation for Eastern Orthodox monasticism, where monastic life remains vibrantly communal, liturgical, and contemplative to this day. The Rule of St. Basil is still followed in many Eastern monasteries.

St. Benedict of Nursia: The Western Monastic Father

The collapse of the Roman Empire in the West left a cultural and spiritual vacuum. Into this, St. Benedict of Nursia (c. 480–547 CE) offered a new path.

Born into a noble Roman family, Benedict left behind the chaos of society for a life of solitude. After years of living as a hermit in Subiaco, Italy, his reputation for wisdom and discipline attracted followers. Eventually, around 529 CE, he founded the monastery at Monte Cassino, and wrote the Rule of St. Benedict, a text that would become the backbone of Western monasticism.

Benedict’s Rule emphasized balance—between prayer and work, solitude and community, obedience and autonomy. The daily schedule (called the horarium) structured monks’ lives around ora et labora—“prayer and work.” His moderation and deep psychological insight made his Rule both humane and enduring.

Benedict’s vision would shape Benedictine monasteries, which in turn preserved the wisdom of antiquity during the Middle Ages. These monasteries became beacons of learning, culture, and stability, keeping the flame of civilization alight through centuries of turbulence.

Saint Macarius of Alexandria

Among the earliest Christian monks who shaped the desert tradition, Saint Macarius of Alexandria (c. 300–395 CE), also called Macarius the Younger, was a towering figure. A contemporary of Macarius of Egypt, he lived as an ascetic in the Nitrian Desert, eventually becoming a presbyter and prior of the Kellii—a famous community of monastic hermits who lived in silent solitude in their own cells.

Macarius’s community in the el-Natroun Desert grew to include more than 5,000 monks, reflecting the powerful attraction of the monastic life during this period. Though he lived mostly as a recluse, numerous miracles were attributed to him, and he is remembered for his strict discipline and spiritual leadership. Inspired by the rigorous Tabbenesiot rule established by Pachomios the Great, Macarius helped set the tone for cenobitic organization and monastic rigor in the Egyptian wilderness.

The Dwellings of Monastics: Monasteries, Friaries, and Convents

Throughout history, monasteries have served as sanctuaries of spiritual practice, centers of learning, and havens of peace and contemplation. The monastery—from the Greek monastērion, meaning “hermit’s cell”—is the traditional dwelling of monks and nuns who seek to withdraw from the world in pursuit of divine communion and inner transformation. These sacred spaces, whether nestled in remote mountains or tucked quietly within cities, form the beating heart of monastic life.

The Architecture of Solitude

Monasteries are often large, self-contained complexes that include monks’ cells, meditation halls, gardens, libraries, kitchens, and refectories (communal dining halls). The layout reflects both the ascetic values of simplicity and the practical needs of daily monastic life.

These sacred grounds may also include ornate shrines, pagodas, temples, drum and bell towers, and sometimes a guest hall for pilgrims. More elaborate monasteries often contain lecture halls, business offices, infirmaries, and schools of study—reflecting the monastery’s role not only as a retreat from the world but as a light unto it.

Monks and nuns often tend gardens, vineyards, or livestock, and may employ lay brothers or sisters for physical labor, allowing full-time monastics to focus on prayer, meditation, and study. Many monasteries sustain themselves economically through agriculture, artisanal crafts, and hospitality. Guesthouses and gift shops offer food, rest, and spiritual tokens—such as relics, icons, and devotional items—to pilgrims and tourists.

Types of Religious Dwellings

Types of Religious Dwellings

In the Christian tradition, the specific terms used to describe these dwellings reflect different spiritual communities and styles of life:

- Monastery: A home for monks or nuns who follow a structured rule (regula), emphasizing stability, prayer, and communal labor. Common in both Eastern and Western Christian traditions.

- Abbey: A type of monastery led by an abbot or abbess. It may function with a greater degree of independence and status.

- Priory: A lesser or dependent house often led by a prior or prioress.

- Friary: The residence of friars, members of mendicant orders who travel and preach rather than reside in fixed communities.

- Convent: Originally any gathering of religious people, the term now often refers to communities of religious sisters or nuns, particularly in Roman Catholic and Anglican contexts.

- Canonry: The dwelling of canons regular, who live in community under a rule but also serve in public ministry.

From Ancient Shrines to Sacred Estates

People have gathered in sacred spaces since the dawn of civilization. Stonehenge, dating back over 5,000 years, and Göbekli Tepe in modern-day Turkey (c. 9000 BCE), testify to humanity’s ancient urge to commune with the divine. The first formal Buddhist monasteries emerged in India around the 4th century BCE, when monks transitioned from wandering ascetics who slept under trees to communal dwellers practicing together in shared spiritual discipline.

While some orders remain mendicant and mobile, such as friars in urban centers, others embrace cenobitic life—structured communal living under a spiritual rule. Both forms contribute to the sacred geography of monastic civilization, from the rock-hewn cells of the Egyptian Desert Fathers to the flower-strewn cloisters of European abbeys.

Sacred Space, Sacred Life

Monasteries—whether they rise from the stones of a desert, the forests of Asia, or the hills of Europe—are more than just buildings. They are temples of the soul, where silence is kept, wisdom preserved, and life is lived with profound intentionality. From their meditation halls and libraries to their gardens and chapels, monastic dwellings represent humanity’s highest aspirations for inner peace, spiritual discipline, and service to the greater good.

Understanding Christian Monastic Architecture: The Sacred Geometry of Withdrawal

Christian monastic architecture is more than an arrangement of buildings—it is a spatial theology, a material embodiment of withdrawal from the world and movement toward God. Every cloistered hallway, every vaulted chapel, every walled garden speaks the language of discipline, contemplation, and transcendence. To understand a monastery is to enter a world shaped not just by stone, but by silence, rhythm, and sacred order.

1. The Layout: A World Within Walls

Monasteries were traditionally built to reflect a microcosm of the heavenly order. Following the Rule of St. Benedict and other monastic customs, the typical layout was highly intentional:

- The Cloister: The heart of the monastery, the cloister is a quadrangle surrounded by covered walkways, symbolizing both inner retreat and spiritual passage. It provides access to key areas like the church, refectory, chapter house, and dormitories, while also functioning as a meditative space in itself.

- The Church: Always the focal point, the monastic church is usually aligned on an east-west axis, symbolizing Christ as the light rising in the East. The choir stalls and apse were designed for the chanting of the Divine Office, performed in prescribed hours throughout the day and night.

- The Chapter House: This room functioned as the administrative and spiritual council chamber where monks gathered daily for readings, communal decisions, and confessions.

- The Refectory: The dining hall, often oriented perpendicular to the church, was a place of communal silence and spiritual reading during meals, emphasizing bodily discipline and shared life.

- The Dormitory: Usually placed above the chapter house or along the cloister, the dormitory emphasized simplicity and uniformity, with monks sleeping in identical cells or shared halls, facing the same direction.

- The Guesthouse and Infirmary: While the monastery was a place of withdrawal, hospitality and care were Christian duties. Separate structures housed guests and the sick, expressing compassion without disrupting the rhythm of the cloister.

2. Symbolism and Sacred Geometry

Monastic builders worked with a symbolic language of form and proportion, heavily influenced by Biblical numerology and classical geometry:

- Circles and squares represented perfection and stability.

- Three-part divisions echoed the Trinity.

- Sevenfold patterns referenced spiritual completion (as in the seven hours of prayer).

- The cloister’s four walks might symbolize the four Gospels, the four cardinal virtues, or the four directions—an inward path to the center.

Vaulted ceilings, ribbed arches, and pointed spires all directed the eye—and the soul—upward, lifting the monk’s awareness toward divine things.

3. Regional Styles and Variations

While the basic elements remained constant, regional monastic traditions expressed themselves through distinct architectural styles:

- Romanesque monasteries (e.g. Cluny, France) featured rounded arches, massive walls, and solemn, fortress-like symmetry.

- Gothic monasteries (e.g. Cistercian houses like Fontenay) introduced light and height—symbols of divine presence—with pointed arches and ribbed vaults.

- Byzantine monasteries (e.g. Mount Athos) used centralized domes and richly iconographic interiors, emphasizing mystical union over linear hierarchy.

- Ethiopian and Eastern monastic architecture adapted monastic ideals to cave churches, desert cells, and remote mountaintop compounds, embodying radical solitude and resilience.

4. Function and Formation: Architecture as Spiritual Formation

Monastic architecture was not only about buildings—it was about forming habitus. It created an environment where time, space, and movement trained the soul:

- Daily rhythm followed the Liturgy of the Hours, regulated by bell towers and sunlight.

- Spatial boundaries supported inner discipline—each space had a purpose, each movement a meaning.

- Silence was not empty but acoustic design; thick walls, enclosed gardens, and stone floors created the necessary stillness for listening to God.

Thus, monastic architecture was a spiritual pedagogy—a living grammar of walls and windows that formed monks not just to live apart from the world, but to become channels of grace within it.

Excellent choice. Here’s an expanded version of the previous section, now incorporating seven significant monastic sites across both Eastern and Western Christianity, each serving as a physical embodiment of monastic ideals adapted to their place, history, and theological focus.

Monastic architecture is not simply functional—it is spiritualized space, designed to cultivate stillness, discipline, and divine contemplation. Across centuries and continents, monasteries have taken different forms while preserving a shared core: to create an ordered world within the world, where human life aligns with sacred rhythm and sacred purpose.

This section explores the general principles of Christian monastic design, then profiles seven landmark monasteries—each illuminating a distinct architectural and spiritual tradition.

Core Principles of Monastic Design

Monastic architecture across Christian traditions is guided by:

- Axial alignment (typically east-west, toward the rising sun/Resurrection)

- Cloistered layout: an inward-facing quadrangle of silence and order

- Specialized spaces: church, chapter house, refectory, dormitory, guesthouse

- Symbolic geometry: numerological and architectural patterns that mirror divine harmony

- Material austerity or ornamentation, depending on theological emphasis (e.g., Cistercian simplicity vs. Byzantine iconographic richness)

Now let us look at how these ideals are expressed across some of the most significant monastic sites in Christendom.

1. Saint Catherine’s Monastery (Sinai Peninsula, Egypt)

Eastern Orthodox | Desert Monasticism | Fortress of the Spirit

Founded in the 6th century at the foot of Mount Sinai, this UNESCO World Heritage site is one of the world’s oldest continuously operating Christian monasteries. Its thick granite walls and remote setting emphasize isolation, resilience, and ascent toward God. The monastery houses the Burning Bush Chapel, where tradition holds that Moses encountered God. Its architecture mirrors early Byzantine forms and includes domes, defensive towers, and intricate mosaics—integrating the spiritual and the elemental.

2. Mater Ecclesiae Monastery (Vatican City)

Contemplative Life in the Heart of the Church

A modern contemplative monastery built within the Vatican Gardens, Mater Ecclesiae was founded in 1994 and became globally known when Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI retired there in 2013. Unlike medieval abbeys, this monastery is intimate and integrated into the daily rhythm of the Vatican, symbolizing contemplation in the center of power. Its architectural modesty is intentional, underscoring the primacy of prayer over presence.

3. Mount Athos (Greece)

Eastern Orthodox | Ascetic Republic | Living Tradition

Mount Athos, a semi-autonomous monastic state on a Greek peninsula, is home to 20 major monasteries and dozens of hermitages. Its architecture blends Byzantine domes, stone-paved courtyards, high defensive walls, and vibrant frescoed interiors. Athonite monasteries embody the Eastern Christian emphasis on hesychia (inner stillness), iconography, and the communal pursuit of theosis (union with God). The landscape and buildings form a spiritual ecology of silence, liturgy, and sacred art.

4. Monte Cassino (Italy)

Benedictine Rule | Foundational Site | Rebuilt Resilience

Founded by St. Benedict himself in the 6th century, Monte Cassino is the cradle of Western monasticism. Its architecture has been destroyed and rebuilt multiple times (most notably during World War II), symbolizing the spiritual persistence of the Rule. Its layout follows the classic Benedictine plan—cloisters, basilica, scriptorium, refectory—organizing monastic life around prayer, work (ora et labora), and community.

5. Westminster Abbey (London, UK)

Benedictine Origins | Liturgical Grandeur | Royal Legacy

Though no longer a functioning monastery, Westminster Abbey began as a Benedictine community in the 10th century and retains the full architectural legacy of monastic life: cloisters, chapter house, refectory foundations, and choir stalls. Its Gothic style, soaring vaults, and long nave reflect a vision of sacred kingship and eternal praise. The abbey represents the integration of monastic rhythm with national ritual, hosting coronations, funerals, and royal liturgies.

6. Cluny Abbey (France)

Cluniac Reform | Liturgical Opulence | Monumental Scale

At its height in the 11th and 12th centuries, Cluny Abbey was the largest church in Christendom, and the spiritual center of a network of over 1,000 Cluniac monasteries. Cluny embodied a monastic vision rooted in divine liturgy and cosmic beauty, with its vast nave, radiating chapels, and elaborately carved capitals. The architectural grandeur reinforced its spiritual aim: unceasing praise of God through highly ritualized worship.

7. Saint John’s Abbey (Minnesota, USA)

Modern Monasticism | Liturgical Space | Concrete and Light

Designed by Bauhaus architect Marcel Breuer in the 1950s, St. John’s Abbey Church is one of the most architecturally bold expressions of modern Benedictine monasticism. Its massive bell banner, minimalist concrete forms, and stained-glass honeycomb facade express a contemporary spirituality rooted in light, geometry, and openness. St. John’s proves that monastic ideals—order, rhythm, silence—can be translated into modern materials without loss of sacred function.

Conclusion: Architecture as Ascetic Language

From Sinai’s desert silence to Cluny’s chant-filled halls, from Byzantine towers to modernist concrete chapels, Christian monastic architecture expresses a single truth in many forms: the journey inward and upward toward the Divine.

Each monastery is a sacred vessel—a spatial covenant between heaven and earth, silence and song, structure and spirit. To walk its halls is to walk the path of intentional life—a geometry not of power, but of peace.

Life in the Monastery: Ritual, Prayer, and Work

To enter the monastery was to step into a world defined by rhythm—an order of time sanctified through prayer, labor, and study. From the early dawn to the deep night, every hour was dedicated to cultivating the soul and sustaining the community. The monastery was not a retreat from the world alone—it was a laboratory for a new way of life.

The Divine Office: Praying the Hours

At the heart of monastic life was the Divine Office (also called the Liturgy of the Hours), a cycle of prayer observed at fixed times throughout the day and night. Drawn from the Psalms and Scripture, this rhythmic devotion sanctified time itself, marking the passage of hours with hymns, chants, readings, and silence.

In Benedictine communities, the day was divided into eight canonical hours:

- Matins (Vigils) – before dawn, a deep, nocturnal vigil of praise

- Lauds – at sunrise, greeting the new day with thanksgiving

- Prime – early morning, invoking divine guidance for the day’s labor

- Terce – mid-morning

- Sext – midday

- None – mid-afternoon

- Vespers – at sunset, offering praise for the day’s blessings

- Compline – before retiring, a gentle descent into night’s silence

This continual cycle of worship united the community and imbued every moment with sacred significance. Chanting the Psalms, meditating on Scripture, and keeping silence became a contemplative thread woven through the fabric of daily existence.

Labor: Ora et Labora

Work was not separate from worship—it was part of it. The Benedictine motto, Ora et Labora (“Pray and Work”), reflected the idea that labor, done with intention and humility, was itself a spiritual discipline.

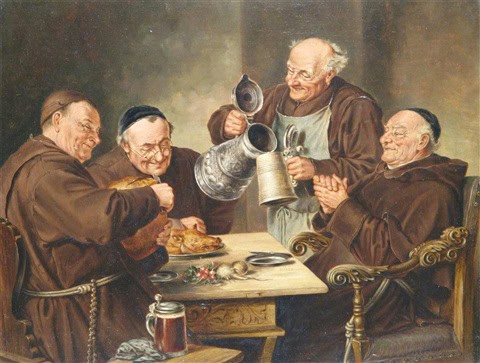

Monks worked the fields, copied manuscripts, tended gardens and livestock, brewed ale, baked bread, cared for the sick, and constructed the very monasteries they lived in. Their labor sustained not only their own communities but often the poor and pilgrims who came seeking refuge.

In scriptoria, monks meticulously copied texts—Scripture, classical philosophy, histories, and scientific works. These scriptoria became the intellectual engines of medieval Europe, preserving the heritage of antiquity and fostering a nascent scholastic tradition.

Silence, Solitude, and Study

While communal prayer and work structured the day, silence and solitude were revered as necessary for the inner life. Most monastic Rules prescribed designated hours of silence, and speech was to be measured, purposeful, and humble.

Time was also dedicated to lectio divina, or “divine reading,” a meditative, slow reading of Scripture that invited the monk not just to understand but to encounter the sacred text. This prayerful study was a way of shaping the heart and mind toward divine truth.

For the monastic, life itself was a sacred liturgy, a slow unfurling of the soul toward God, shaped by obedience, simplicity, and devotion.

Fourth Century St. Catherine’s Monastery, the World’s Oldest Continually Operating Library

Hesychasm: The Way of Stillness

Hesychasm (from the Greek hesychia, meaning “stillness” or “silence”) is a mystical tradition within Eastern Orthodox Christianity that emphasizes inner quiet, continual prayer, and the direct experience of the divine. Rooted in the spiritual teachings of the Desert Fathers and developed in the Byzantine monastic tradition, Hesychasm reached its mature form in the monasteries of Mount Athos during the 13th and 14th centuries.

The core practice of Hesychasm is the Jesus Prayer:

“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

This prayer is repeated continually—mentally and often in rhythm with the breath—to cultivate a state of inner stillness and unceasing prayer, as described in the New Testament (“Pray without ceasing” – 1 Thessalonians 5:17).

Hesychasts aim to quiet the mind (the nous) from distractions and turn it inward, descending into the heart where true communion with God is believed to occur. This inward journey often leads to what is called theosis—union with God—sometimes accompanied by the experience of the uncreated light, understood to be the same divine light revealed during Christ’s Transfiguration on Mount Tabor.

Prominent defenders and theologians of Hesychasm include St. Gregory Palamas, who articulated its theological basis in opposition to critics like Barlaam of Calabria. Palamas emphasized that while God’s essence remains unknowable, His energies (such as the uncreated light) can be experienced by the purified heart.

Today, Hesychasm remains a living tradition, practiced by Eastern Orthodox monks and laypeople seeking transformation through simplicity, silence, and the prayer of the heart.

Manuscript Culture: Preserving the Sacred and Classical Legacy

Long before the rise of modern printing, the safeguarding of knowledge depended on the careful work of scribes. In the monasteries of late antiquity and the Middle Ages, manuscript culture flourished—anchored by the belief that copying sacred and classical texts was not just labor, but a sacred act of devotion.

Cassiodorus and the Monastic Intellectual Tradition

One of the earliest visionaries of this tradition was Flavius Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus (c. 485 – c. 585), a Roman statesman, scholar, and Christian Neoplatonist. After serving as magister officiorum (chief of government) under Theodoric the Great, Cassiodorus retired to his estates in southern Italy, where he founded the Monastery of Vivarium. More than a spiritual retreat, Vivarium was a cultural beacon, establishing one of the first monastic scriptoria—places where texts were carefully copied, preserved, edited, and illuminated.

Cassiodorus saw monastic life as a sacred opportunity for education and preservation. In his instructional work, the Institutiones, he outlined a curriculum for monastic learning that would later inspire the Trivium and Quadrivium—the foundation of medieval liberal arts education. The first part of the Institutiones focused on Scripture, urging monks to begin their studies with the Psalms.

The second part addressed secular learning, including grammar, rhetoric, dialectic, arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy, alongside authors like Virgil, Socrates, and Ptolemy. Yet, Cassiodorus reminded his monks that “All wisdom comes from the Lord” (Ecclesiasticus 1:1), underscoring the harmony of faith and reason.

Though Vivarium was not governed by a strict monastic rule, its educational rigor set new standards. Cassiodorus did not expect all monks to become scholars. Those less inclined to study were encouraged to take up agriculture, which he saw as holy labor. Drawing from Virgil’s Georgics and the Psalms, he described farming, gardening, and beekeeping as fitting occupations for monks in harmony with divine purpose.

The Rise of the Scriptorium and Editorial Curation

Cassiodorus introduced innovative methods of textual curation. He personally annotated manuscripts, praising passages aligned with Church orthodoxy using a symbol called the chrismon, and marking disapproved content with the achriston. His Vivarium library became a sanctuary of curated theological and classical knowledge.

The scriptorium at Vivarium was among the first to systematically prioritize the preservation of ancient texts, both sacred and secular. This methodical approach influenced future generations of monasteries, transforming the haphazard copying of manuscripts into a disciplined art.

Scribes as Vessels of Contemplation

Nearly a thousand years later, during the era of the printing press, Abbot Johannes Trithemius of Sponheim wrote De Laude Scriptorum (“In Praise of Scribes”, 1492) to defend the enduring value of hand-copying manuscripts. Writing to Gerlach, Abbot of Deutz, Trithemius declared that transcription remained essential to monastic education and spiritual formation:

“The printed book is made of paper and, like paper, will quickly disappear. But the scribe working with parchment ensures lasting remembrance for himself and for his text.”

To Trithemius, copying was more than preservation—it was contemplation, a discipline that sharpened understanding and deepened the monk’s communion with sacred truths. The armarius, or director of the scriptorium, oversaw this sacred labor. It was his duty not only to supply writing materials and supervise scribes, but also to ensure each monk received a book at the start of Lent for meditative reading—a tradition that marked the beginning of what historians now call manuscript culture.

Legacy and Influence

Cassiodorus was deeply influenced by Greek and Latin Church Fathers, valuing the works of Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Basil the Great, and John Chrysostom, though he favored Latin authors for his Italian audience—especially Jerome, Augustine, Ambrose, and Hilary. His curatorial vision helped define what Christian Europe would preserve, read, and revere for centuries.

In addition to these theologians, Cassiodorus also drew inspiration from Martianus Capella, a 5th-century Neoplatonist whose allegorical treatise On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury laid the groundwork for the seven liberal arts. This encyclopedic vision shaped the educational mission of monasteries, linking divine wisdom to the structured learning of grammar, logic, music, and the natural sciences.

From Vivarium to Sponheim, manuscript culture was not just the copying of words—it was the cultivation of civilization. Through ink, parchment, and prayer, the monks of these scriptoria became guardians of wisdom, ensuring that both sacred scripture and the intellectual heritage of antiquity would survive into the modern world.

Magic, Monks, and the First Universities

In the High Middle Ages (c. 1000–1300 CE) and Late Middle Ages (c. 1300–1500 CE), the seeds of modern higher education were sown in the form of cathedral schools, which evolved into the first universities.

These institutions—such as those at Paris, Bologna, and Oxford—became centers of theological debate, philosophical inquiry, and early scientific thought. Within these scholastic circles, a few scientifically minded thinkers began to push the boundaries of knowledge, even under the watchful eye of ecclesiastical authority.

At Merton College, Oxford, during the 14th century, a group known as the Oxford Calculators developed an analytical, mathematical approach to natural philosophy. These thinkers were precursors to later scientific empiricists, employing logic and quantification to explore motion, time, and force.

However, their momentum was abruptly halted by the catastrophe of the Black Death in 1348. The plague decimated a third of Europe’s population—especially in urban centers where innovation had been growing—and cast a long shadow over intellectual progress for generations.

It wasn’t until the Scientific Revolution of the 16th century that science began to fully rebound. This transformative period, typically marked by the publication of Nicolaus Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, 1543), introduced the heliocentric model of the solar system. This bold claim directly challenged both the Aristotelian worldview and biblical interpretations that had placed Earth at the center of the cosmos.

During the earlier medieval centuries, questioning Scripture or Church-sanctioned doctrine could carry grave consequences. Theological orthodoxy dominated education, and speculation beyond approved texts often led to accusations of heresy, sorcery, or worse. In this environment, ancient pagan sciences—such as alchemy, astrology, and Hermetic philosophy—survived only through concealment and symbolic language, often passed down and preserved within monastic scriptoria or cloaked in Christian allegory.

“Magic was the medicine of Europe in the Dark Ages.”

Indeed, folk magic and mysticism served as the primary healing arts in early medieval Europe. Even widely known incantations such as “Abracadabra” were used as charms against illness, inscribed on amulets or talismans thought to protect the wearer from plague and demonic affliction. While the Arab world advanced Greek medical theory and pharmacology, many Europeans relied on saints’ relics, pilgrimage, and miracles as sources of healing.

Still, within monasteries, the seeds of a more empirical medicine took root. Monastic communities cultivated herb gardens, served as hospitals, and maintained therapeutic knowledge that bridged spiritual care and rudimentary medicine.

At the same time, the requirement of Latin literacy to read the Vulgate Bible exposed scholars and clergy to Classical authors. Monks, especially in Ireland, became tireless copyists and translators, salvaging fragments of Greek and Roman knowledge that might otherwise have been lost.

Thus, paradoxically, while medieval Europe saw science constrained under the weight of dogma and superstition, it was also in the monasteries and nascent universities—among scribes, friars, and scholars—that the ancient embers of rational inquiry were kept alive. These embers would eventually flare into the light of the Renaissance and the birth of modern science.

Monasticism and the Wider World: Culture, Care, and Controversy

Although monasteries were built to be havens of spiritual retreat, they became vital centers of education, healing, hospitality, and cultural preservation. Far from turning their backs on the world, monastics in many ways transformed it—quietly and steadily, over generations.

Guardians of Knowledge and Art

From the fall of Rome through the medieval period, monks and nuns played a crucial role in preserving the cultural memory of the West. Within the walls of monastic scriptoria, ancient texts were rescued from decay—painstakingly copied and illuminated by candlelight.

Thanks to this work, much of Greek philosophy, Roman law, and early scientific thought survived the chaos of empire collapse.

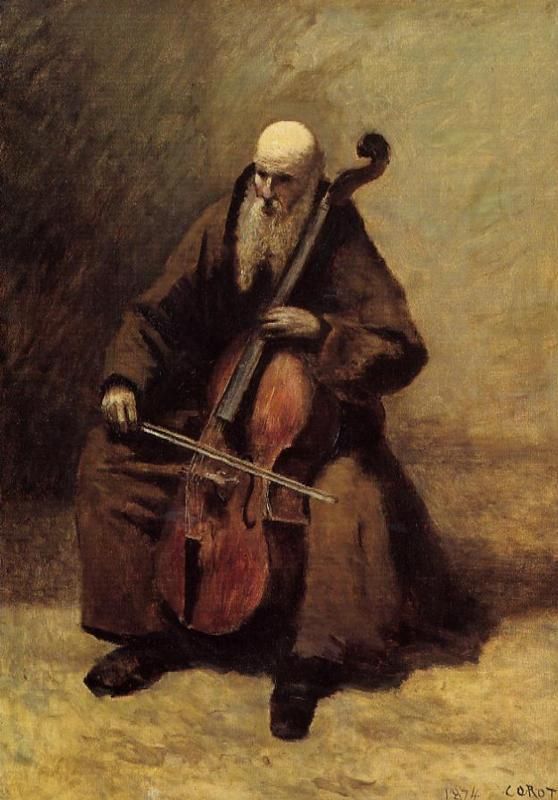

Monks didn’t only preserve the past—they created anew. Gregorian chant, the earliest form of notated Western music, emerged from monastic choirs. Medieval monastic architecture gave rise to the soaring beauty of Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals. Through stone, parchment, and voice, the monastery gave expression to transcendent beauty.

Hospitals, Hospitality, and Human Dignity

Monasteries were hospitals for the body and the soul. Long before public healthcare, monastic infirmaries tended the sick with compassion and skill. Herbal medicine, hygiene, and early medical knowledge were cultivated and passed down within cloisters.

Pilgrims, orphans, the poor, and weary travelers all found shelter in monastic guesthouses. Offering hospitality was not charity—it was a sacred duty. Christ, they believed, might come in the form of any stranger. In this way, monastics quietly built a network of sanctuaries across the known world.

Tension and Reform

But as centuries passed and monasteries grew in wealth and influence, the simplicity of early ascetic life sometimes gave way to luxury and politics. Tensions arose between the vow of poverty and the realities of land ownership and power.

This led to cycles of reform movements: the Cluniac reform in the 10th century, emphasizing liturgical beauty and monastic independence; the Cistercian movement of the 12th century, calling for a return to manual labor and austerity; and the Franciscan and Dominican orders, which emerged in response to urban poverty and spiritual hunger.

These movements reminded the Church—and the world—that monasticism’s deepest call is to authentic inner transformation, not outward privilege.

The Torch is Passed

The twilight of the classical world gave way to centuries of preservation, transformation, and transmission. During the long arc of the Middle Ages, the embers of ancient wisdom were carefully tended—first by Christian monastics, then by Muslim scholars, and finally by a new generation of European thinkers ready to reignite the flame of inquiry. This moment of handoff—between civilizations, languages, and cultures—marks the vital transition from the ancient to the modern scientific worldview.

As early as the eleventh century, Saint Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109) sought to reconcile Christian faith with rational inquiry, setting the stage for centuries of scholastic exploration. In the next century, Peter Abelard advanced these efforts through dialectic and logical analysis, introducing critical methods that would soon shape European intellectual life.

Their philosophical legacy was taken further in the thirteenth century by Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln, who added observation, experimentation, and inductive reasoning to the scholastic toolkit. Grosseteste’s approach marked a turning point in the intellectual method: an early formulation of the scientific method.

Yet the true explosion of knowledge in the West began with a pivotal cultural event: the translation movement of the twelfth century. In this period, scholars flocked to centers of learning in Spain, particularly Toledo, where the cultural interchange between Muslim, Jewish, and Christian communities created unparalleled opportunities for intellectual growth. The division of Iberia between Christian and Muslim rulers offered scholars access to Arabic texts on science, philosophy, and alchemy—texts that had preserved and expanded upon the works of the Greeks.

Among the first of these translators was Robert of Chester (Latin: Robertus Castrensis), an English scholar who, in 1144, completed the first known Latin translation of an Arabic alchemical text: Liber de Compositione Alchimiae. He followed this in 1145 with a Latin translation of Al-Khwarizmi’s seminal treatise on algebra (Liber algebrae et almucabola), a foundational work for European mathematics.

Contemporary with Robert of Chester was Robert of Ketton (Latin: Robertus Ketenensis), another Englishman active in Spain, who completed the first Latin translation of the Qur’an and other key scientific and astronomical texts. While some scholars suggest Chester and Ketton may be the same person, historical records place them in different regions of Spain—Segovia and Navarre, respectively—underscoring the widespread activity of English translators on the Iberian Peninsula.

Other major contributors to the translation movement included Adelard of Bath, who brought the works of Euclid and Al-Kindi to Europe, and Gerard of Cremona, who translated over 70 Arabic works, including those by Avicenna, Al-Razi, and Ptolemy. These translations introduced essential vocabulary to the Latin lexicon—alchemy, alcohol, elixir, carboy, athanor—and opened the intellectual floodgates for the European revival of science.

By 1200, Europe had begun to absorb the full scope of Arabic and Greek science. This confluence of knowledge fueled the rise of European alchemy, and soon names like Artephius, Peter of Abano, Arnald of Villanova, and Raymond Lull emerged in both legend and literature. Their writings—spanning medicine, Hermeticism, mysticism, and proto-scientific theories—kept alive the spirit of ancient inquiry, even as the Inquisition labeled them heretics or sorcerers.

The broader historical backdrop was also key. Though the Crusades failed militarily, they succeeded in fostering cross-cultural contact, travel, and trade. Following the Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople in 1204, Latin scholars gained access to original Byzantine Greek manuscripts.

Translators like William of Moerbeke began to produce faithful Latin editions of Aristotle, Archimedes, and Proclus, unmediated by Arabic versions. With the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, a wave of Byzantine refugees brought with them libraries of classical Greek texts, which played a pivotal role in the Renaissance.

This Renaissance—literally a rebirth—was not a spontaneous eruption of genius, but the culmination of centuries of cross-cultural knowledge transmission. The flame of science passed from Alexandria, to Baghdad, to Toledo, to Paris and Oxford. In each place, it was sheltered, nurtured, and refined—until finally, in the sixteenth century, it would burst forth in full brilliance with the dawn of modern science.

The torch, long carried through monasteries, deserts, libraries, and laboratories, had been passed at last into the hands of a new world.

The University: A Temple of Knowledge

Lifelong learning is a vital part of maintaining not only intellectual vitality but also holistic health. The pursuit of wisdom—through science, the liberal arts, and the humanities—is a defining characteristic of our species. Since antiquity, the university has stood as a symbol of this pursuit: a community where minds gather to explore, question, and refine our understanding of the cosmos and ourselves.

Origins: From Temple to Classroom

The origins of the university can be traced back to the Musaeum of Alexandria, a remarkable institution of the ancient world that combined library, research academy, and temple into a single learning complex. In this way, the university inherited the mantle of the temple: a sacred space for contemplating the deepest questions of existence.

The Latin word universitas—originally meaning a “guild” or “corporation”—emerged in medieval Europe to describe communities of teachers and students bound together by shared purpose and mutual discipline. These associations evolved out of cathedral and monastic schools, where monks and nuns preserved and taught Classical and Christian knowledge.

Indeed, it was under the auspices of the Roman Catholic Church that the first Western universities arose. The cathedral school and the monastic school were the precursors to medieval universities. These early institutions were often attached to cathedrals or large abbeys and taught Latin literacy, sacred scripture, and basic sciences—especially grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy—the so-called trivium and quadrivium of the liberal arts.

Guilds, Mysteries, and the Rise of the University

As medieval towns grew in size and influence, so too did the artisan guilds: tightly organized associations of tradespeople such as masons, carpenters, weavers, and glassblowers. These groups maintained the “mysteries” of their crafts—secret knowledge passed from master to apprentice. From this guild framework arose the first universities, which were themselves structured as guilds—either of students (as in Bologna) or of masters (as in Paris).

In this sense, universities were not just centers of knowledge but also institutions of social formation and cultural preservation, transmitting the intellectual “crafts” of theology, law, medicine, and philosophy. Like the artisan guilds, universities guarded and cultivated their own ars studiorum—the art of study.

The four oldest extant universities are:

- University of Bologna (founded 1088, Italy) – focused on law

- University of Oxford (at least 1096, England) – focused on theology and liberal arts

- University of Paris (c. 1150, France) – birthplace of Scholasticism

- University of Cambridge (1209, England) – an offshoot of Oxford

The Age of Canon Law and Church Influence

In the 12th century, the codification of church law in Gratian’s Decree systematized ecclesiastical jurisprudence, becoming the core text for students of canon law. Church councils, such as the Synod of Worms, reshaped the balance of power between Church and State, while canon lawyers rose to prominence in both religious and secular spheres.

As the influence of the Church grew, so too did the excesses of its bureaucracy. The selling of indulgences, nepotism, and doctrinal rigidity ultimately provoked intellectual and spiritual reform movements—some of which would help usher in the Renaissance and Reformation.

The Three Degrees of Learning

The traditional academic hierarchy still found in modern universities follows a model developed in the Middle Ages:

- Bachelor’s Degree – denoting readiness for further specialization

- Master’s Degree – allowing the holder to teach and supervise

- Doctorate – recognizing the authority to innovate and expand knowledge within a field

These degrees originally represented the trivium and quadrivium disciplines, evolving into today’s modern fields of study.

Beyond Academia: A Place for the Whole Person

Although contemporary universities are often seen as feeders for the corporate world, their deeper purpose has always been greater than job training. The university is a microcosm of civilization—a studium generale—a place where the arts, sciences, and humanities converge to shape the minds that will shape the world.

In the words of philosopher and abbot Johannes Trithemius (1462–1516), writing in In Praise of Scribes at the dawn of the printing press:

“The scribe working with parchment ensures lasting remembrance for himself and for his text. The printed book may disappear; the written word endures.”

In our time, the university must again strive not merely to educate for employment, but to form wise, free, and responsible human beings—capable of critical thought, creative vision, and compassionate leadership.

Scholastic Roots and Modern Methods: The Evolution of Learning

The earliest universities in medieval Europe relied on the Scholastic Method, a structured form of reasoning based on disputation, where students and teachers would argue both sides of a given question, usually grounded in authoritative texts like the Bible or the works of Aristotle. The aim was to arrive at truth through careful dialectic: by asking, contradicting, resolving.

This rigorous process sharpened intellectual agility and built the critical frameworks that would later guide scientific inquiry, legal reasoning, and theological reflection. In this crucible of conversation, the disciplines of logic, grammar, and rhetoric formed the foundation for what would become the modern university curriculum.

The Modern University: From Halls to Hubs

Today, the modern university continues to draw from its Scholastic and Enlightenment roots, while also embracing contemporary technology and pedagogy:

1. Lecture and Seminar

- Lectures remain a staple of university life, offering expert-driven instruction in foundational concepts.

- Seminars provide smaller, interactive forums for critical discussion and collaborative learning, often emphasizing Socratic dialogue.

2. Research-Based Learning

- Students are trained not merely to consume knowledge, but to produce it through research projects, lab experiments, and fieldwork.

- Emphasis is placed on peer review, citation, and ethical inquiry, modeled after the scientific method.

3. Interdisciplinary Studies

- Inspired by the liberal arts tradition, modern universities increasingly promote cross-disciplinary learning.

- Programs in environmental science, data ethics, cultural studies, and digital humanities reflect this evolving landscape.

4. Online and Hybrid Learning

- With the rise of the internet, digital platforms such as Canvas, Moodle, and Zoom have transformed traditional education.

- Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) allow global access to world-class instruction, democratizing learning at an unprecedented scale.

5. Project-Based and Experiential Learning

- In many programs, especially in engineering, business, and the arts, students now engage in real-world projects, often in collaboration with industry, NGOs, or communities.

- Internships, co-op placements, and study abroad programs provide hands-on experience that bridges theory and practice.

6. Artificial Intelligence and Personalized Learning

- AI-driven analytics are beginning to tailor educational experiences to individual students, adapting pacing and content to optimize outcomes.

- Tools like adaptive quizzes, chatbots, and virtual tutors offer support in increasingly intelligent ways.

A Temple of Wisdom for a Global Age

From the scriptoria of medieval abbeys to the supercomputers of today’s research labs, the university has remained a beacon of humanity’s quest for knowledge. It is a sanctuary of truth-seeking, where ancient wisdom meets modern curiosity—where memory, meaning, and method converge.

Though its form has changed, the purpose endures: to awaken the mind, to cultivate the soul, and to shape a more conscious civilization.

In this spirit, the university of the future must remember its sacred legacy. For the truest education is not merely the training of the hand or the filling of the head—but the formation of character and the illumination of the heart.

The Decline and Renewal of Christian Monasticism

Monasticism, like all living traditions, has seen periods of both decline and renewal. Shaped by war, politics, and evolving spiritual needs, it has never remained static—but always, in some way, endured.

The Reformation and Secularization

In the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation swept across Europe, radically reshaping the religious landscape. Many Reformers criticized monasticism for being unbiblical, overly hierarchical, and out of touch with the people. As a result, thousands of monasteries in Germany, Switzerland, Scandinavia, and England were closed, destroyed, or seized by the state.

This was a profound turning point. Once-vast networks of religious houses were dismantled. Libraries were scattered or burned. Centuries of prayer, learning, and labor were suddenly disrupted. In some regions, Christian monasticism was thought to be fading into history.

Catholic Renewal and New Orders

But in the Catholic world, a countercurrent of revival surged forward. The Counter-Reformation inspired the founding of new orders—Jesuits, Ursulines, and others—that reimagined monastic life for a changing world. These orders focused not only on contemplation, but also on education, missionary work, and social justice.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, monasteries adapted, declined, and returned again—shaped by Enlightenment thought, revolutions, and the rise of nation-states. The French Revolution, in particular, saw mass closures of religious institutions, and many monks and nuns were martyred or exiled.

Still, monasticism persisted. In the shadows and in remote places, it weathered the storms of history, keeping alive the ancient rhythms of prayer and labor.

Modern Monastic Renewal

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Christian monasticism entered a surprising renaissance. Orders like the Trappists, Benedictines, and Carmelites saw renewed interest, particularly after the devastation of World War I and II, when many people turned again to deeper spiritual roots.

Monasteries became places of retreat for laypeople, offering silence, hospitality, and a sacred rhythm in a disorienting modern world. Contemplative orders, such as the Carthusians, attracted seekers longing for depth and stillness. Some monks—like Thomas Merton, the Trappist writer—became modern voices for spiritual renewal.

Monasticism in the Digital Age

Today, monastic communities face new challenges: declining vocations, aging populations, and rapid societal change. But they also find new vitality in interfaith dialogue, ecological stewardship, digital outreach, and the global retreat movement.

Some orders are thriving in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Others are opening their doors to spiritual seekers of all backgrounds. While numbers may be smaller than in past centuries, the spirit of monasticism remains surprisingly relevant—perhaps even prophetic—in a world often starved for stillness, service, and simplicity.

Monasticism’s Gifts to the Modern World

In a world of constant noise, information overload, and spiritual restlessness, the legacy of monasticism offers more than nostalgia—it offers medicine. From the ancient cloisters of the Benedictines to the global mission fields of the Jesuits, Christian monasticism continues to shape culture, conscience, and community in powerful, often unseen ways.

The Benedictine Legacy: Ora et Labora

Founded in the 6th century by St. Benedict of Nursia, the Benedictine Order gave Christian Europe a profound gift: a rule of life rooted in prayer, work, humility, and stability. Ora et labora—“pray and work”—became the sacred rhythm of monastic life.

For centuries, Benedictine monasteries served as:

- Centers of agriculture and economic sustainability

- Guardians of classical knowledge, preserving ancient manuscripts through the Dark Ages

- Refuges of hospitality for pilgrims, the poor, and the displaced

- Schools of spiritual formation for monks and nuns who lived by a daily rhythm of prayer, silence, reading, and labor

Today, Benedictine spirituality inspires not only monks and nuns, but also laypeople seeking to root their daily lives in contemplation, simplicity, and community. The Rule of St. Benedict—written over 1,500 years ago—is still used as a guidebook by monastic and non-monastic spiritual communities around the world.

The Jesuit Revolution: Faith that Thinks, Serves, and Educates

In the wake of the Protestant Reformation, the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), founded by St. Ignatius of Loyola in 1540, redefined what monasticism could be in the modern world. Unlike the cloistered life of earlier orders, Jesuits took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience—and were sent into the world, rather than away from it.

Their contributions include:

- Founding some of the world’s greatest universities, including Georgetown, Fordham, Boston College, and the Gregorian University in Rome

- Training missionaries and intellectuals to engage with culture, science, philosophy, and politics

- Establishing a legacy of global education across continents, languages, and traditions

- Pioneering social justice movements, especially in Latin America and Africa

Jesuit spirituality, grounded in the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius, emphasizes discernment, self-examination, and “finding God in all things.” This deeply personal and intellectually rigorous approach continues to shape educators, leaders, and contemplatives across traditions.

Monasteries as Places of Healing and Retreat

In our time, monastic communities—whether Benedictine, Jesuit, Carmelite, or otherwise—serve the broader world by opening their doors to:

- Retreatants seeking silence and spiritual renewal

- Refugees and the unhoused seeking shelter and compassion

- Ecumenical and interfaith dialogue, especially between Christians and Buddhists

- Ecological stewardship, as many monasteries return to sustainable farming, permaculture, and land conservation

Monasteries today are often called “islands of peace” in a culture of haste. Their quiet witness reminds us that human dignity is found not in productivity, but in presence—and that meaning is not manufactured, but discovered.

The Monastic Heart in a Restless World

In an age of digital noise, fractured attention, and spiritual uncertainty, the monastic tradition offers not an escape—but a return. A return to silence, to simplicity, to the sacred rhythms of life often forgotten but never lost.