Contents

- Introduction: Creative Visualization

- Guided Meditation

- Relaxation

- Health and Immunity

- Healing

- Athletics

- Life Goals

- Holistic Imagery for Success

Creative Visualization

When I was a gymnast as a child, my teammates and I were taught to visualize ourselves doing each routine while we were waiting our turn to practice the event. This technique helps gymnasts prepare for difficult exercises that are judged to the tenth of a point on form and execution. Toes must be pointed, knees straight, body in alignment, and advanced skills must be performed with speed and precision. Creative visualization plays an essential part in such serious training because in large part, where the mind goes, the body will follow.

Creative visualization has many forms and uses. Its benefits are manifold and really quite astonishing in depth and scope. Scientific studies have shown the positive effects of creative visualization on health, such as immunity, stress, healing and pain management. Science also shows that it improves many facets of life, from athletic ability to cognitive performance, to self esteem, to goal achievement.

Treatment of anger, stress, anxiety, depression and other emotional issues, along with letting go of bad habits, can have a major impact on self esteem and personal relationships.[1] Visualization techniques may also aid in the attainment of higher states of consciousness. Whatever you need, whatever you do, whatever your abilities, visualization will help.

Mental imagery is a reproduction of perceived aspects of the physical world within a subject’s mind.[2] Neuroscience has demonstrated that the brain can reproduce mental imagery from all of the senses, including sights, sounds, tastes, smells, pressures, textures, temperatures and movements.[3] Mental imagery may be associated with positive or negative emotions.

Experimental psychology has developed therapeutic methods to replace a patient’s imagery that causes pain, depression, anxiety or stress with imagery that is calming, relaxing, comforting, and conducive to cognitive clarity and emotional stability. Visualization acts directly on the brain, altering brainwave activity and biochemistry, and its effects branch out into every aspect of life. There is a lot of research that shows how mental practice boosts confidence, enhances mood, helps the healing process and has a positive effect on performance of cognitive and physical tasks.[4][5][6][7][8]

As a general introduction to the subject of creative visualization, this article will not go into a lot of detail, but citations are given so the interested reader can pursue further information. Future articles will delve deeper into topics like traditional religious visualizations; relaxation exercises; healing with intent; guided meditation; goal-setting; the biological sciences that examine visualization; and the relationship between science and spirituality.

Guided Meditation

Guided meditation is meditation led by a trained expert or teacher who verbally guides an audience through a meditation in person or via audio or video recording. The technical term “guided meditation” is used in academic research, clinical practice of contemporary medicine, and scientific experimentation. Guided meditation may involve relaxation techniques, hypnosis, mindfulness meditation and journaling. Sometimes music or sounds are used to elicit certain moods or emotions as a complement to the verbal instruction and guided imagery.

Guided meditation can be purely instructional, but usually it involves visualization. Guided imagery is the primary element of visualization-centered guided meditation. Guided imagery is a form of therapy used by health professionals to treat disorders by generating, maintaining, inspecting and transforming mental images recreated from sights, sounds, scents, tastes, or feelings.

According to S. M. Kosslyn’s[1] computational theory of visualization, mental imagery may be held in the mind to different degrees, expressed in four stages. Beginning with the simple generation of images, the mind proceeds to maintenance of imagery and then inspection of the object(s) of the image. Finally, there may be the transformation of imagery from negative and painful images to positive and healthy images.[2]

Sense objects are often used in guided imagery meditation, especially sounds, usually music or recordings of nature. Worship music, chanting, and other kinds of song can be experienced as guided visualizations.[3] [4] Classical music or relaxing music is often used, but studies show that various genres are effective, especially when lyrics contain what are perceived to be meaningful affirmations about success.[5]

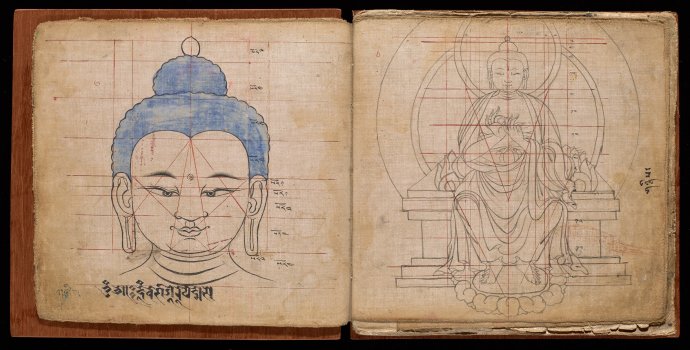

Visual aids like mandalas and visual symbols are found in religious ceremonies and in modern psychotherapy. Ritual, itself, is a form of guided imagery that relies heavily on sensory stimulation.

Not all sense objects used in meditation are related to guided imagery; the senses can be used in several ways to aid meditation. The color and tidiness of a room can have significant effects on the mind. Light can be dimmed for a calming atmosphere. Read material, such as poetry or instruction, may be part of meditation without any visualization involved. Music, chanting, bells, nature, water or other sounds may be simply pleasurable and relaxing.

Scents may be used to induce a specific state of mind, such as the calming effect of lavender, often in the form of essential oils as aromatherapy, or incense. Massage therapy is a touch-based healing modality that may use pressure, joint movements and heat to help induce a meditative state of mind.

Often the initial phase of guided meditation is relaxation. Self-hypnosis or hypnosis by a professional therapist utilizes visualization and deep relaxation to alter brainwaves from Beta (12 to 30 Hz), the normal state, to Alpha (8 to 12 Hz) or Theta (4 to 8 Hz), suggestible states wherein the subconscious can be explored and conditioned. Repeatedly visualizing achieving one’s goals can change patterns of failure to establish a successful mindset that overcomes psychological obstructions and produces positive results.[6]

Relaxation

Visualization is one of several meditation methods that can induce relaxation and relieve stress for improved health.[1] [2] Imagery may be focused upon a remembered location or imaginary environment, such as a beach, an island, a jungle, or any other peaceful, enjoyable setting that makes one comfortable.

This kind of meditation may be supplemented with music or sounds related to the images within the visualization, such as sounds of the ocean, birds or wind through the trees.[3] Visualization can be self-directed or it may be assisted by a guided meditation. It can be joined with other types of relaxation meditations and modalities.

Mental relaxation techniques include the body scan meditation, progressive muscle relaxation, deep breathing, movement meditation like yoga or taijiquan (Tai Chi), guided imagery and mindfulness meditation.[4] The Relaxation Response is a term coined by Harvard University’s Dr. Herbert Benson to indicate meditation techniques that elicit deep relaxation.[5]

It is important to note that different meditations achieve varying positive results. Whereas mindfulness meditation has been shown to affect the sensory awareness and perception regions of the brain, the Relaxation Response exercises the deliberate control neural mechanisms.[6] It follows that a routine that utilized complementary modalities would be ideal for a comprehensive meditation program.

It should be noted that while relaxation techniques are certainly helpful in reducing stress, other psychological modalities, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychotherapy or medication, may be even more helpful. It is essential to one’s health that one seek the advice of a qualified professional medical practitioner for any health-related complaints. That said, visualization techniques have proven to be a significant part of a basic health regimen.

Health and Immunity

Psychoneuroendocrinoimmunology shows how the nervous, endocrine and immune systems are intertwined and how disorders can arise from stress. The article, “Visualization and Stress Relief” goes into more detail on the anatomy and physiology of this process. Stress in the form of loneliness, fear, anger, anxiety, or depression can raise heart rate and blood pressure while lowering immunity. Chronic stress of this kind often undermines homeostasis and health.

Visualization is a uniquely attractive form of medicine. It is an effective preventative therapy as well as a benign remedy for stress and many of its associated disorders. Pharmaceuticals such as antidepressants and psychedelics may be used for similar purposes, but they may come with negative side-effects, which visualization does not. Furthermore, stress relief and managing the many side effects of stress are not the only ways visualization and other forms of meditation can help maintain and improve health.

Visualization may be effective in helping to treat addiction. In one study, seventy-six outpatients with a chemical dependency treatment program were given six hour-long relaxation and visualization exercises over a period of three weeks, replacing the usual treatment of psychoeducation (problem-solving skills). Standard tests revealed that visualization and psychoeducation produced equally positive results.[1] The authors of the study recommend that further research be undertaken to understand the benefits of visualization as a health and healing modality.

Visualization is also used in therapeutic guided imagery. Learning techniques to control one’s mental imagery can be vital to healing from serious psychological afflictions. Mental imagery can exacerbate certain disorders such as PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), eating disorders, multiple sclerosis, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, phobias, anxiety and depression.[2]

Healing

Painful memories or imagined scenarios about the future can cause distress, whether anxiety, depression, or both. Spontaneous vivid mental images called flashbacks can cause anxiety and stress. A flashback is an involuntary onslaught of vivid imagery from past situations that caused intense fear, discomfort, pain or suffering. Similarly, negative imagery can arise that causes or perpetuates depression. Anxiety and depression can exist simultaneously or cycle through the mind.

Just as illness can cause pain through mental imagery, so can creative visualization be a source of healing. Guided imagery can increase relaxation and reduce stress. Cancer patients trained in relaxation techniques and/or guided imagery experience less pain, anxiety and depression.[1] [2] Guided imagery has been shown scientifically to be an effective treatment for both physical and psychological pain, and is an important part of a holistic therapeutic plan.[3]

Guided imagery is used in therapy to teach the patient how to replace painful images, like distressing memories, negative thoughts or worries about the future, with images that calm, comfort, encourage and empower. One can go to a therapist to receive guided meditation face-to-face, or find the appropriate verbal guided meditations recorded on media.

Therapeutic guided meditation may involve several types of guided imagery. Soothing words may be used to calm the mind and relax the body. Instruction may focus on breath control or progressive relaxation techniques. There may be multi-sensory visualizations of real or imaginary peaceful locations, either natural or architectural. A patient may be led to change attitudes, perspectives, ways of thinking, or behaviors, through mental rehearsals of healthier patterns of volitional action and reaction to the environment.

Medical science has made it clear that guided imagery is useful for relaxation, health and healing. Visualization has also been shown to be a key element of physical fitness.

Athletics

Guided imagery has been shown to improve motivation, pain management and endurance in sports.[1] Visualizing athletic skills during downtime improves performance.[2] Many scientific studies have proven that mental training with visualization is an effective strategy for many forms of athletics, from throwing darts and basketball,[3] [4] to sprinting and weight training,[5] to Olympic competitions.[6] [7] [8] [9] Olympic athletes from various disciplines, including gymnastics, diving, judo and fencing, use visualization to prepare for competition.[10]

There is a study supposed to have occured in Russia in 1980, described by the authors of Peak Performance: Mental Training Techniques of the World’s Greatest Athletes, published in 1985. As already stated, many later studies have verified the benefits of visualization on athletic performance. However, I have not personally confirmed the authenticity of these Russian experiments, as I cannot find them recorded by an original source. Until the original source is discovered or the experiment reproduced, and the study reviewed by scientists in related fields, one ought not consider the study to be verified as factual.

The claim in Peak Performance is that Soviet Olympic athletes were divided into four groups to train for hours several times each week. Each group had a different percentage of physical versus mental training.

Group 1 – 100% physical training, 0% mental training

Group 2 – 75% physical training, 25% mental training

Group 3 – 50% physical training, 50% mental training

Group 4 – 25% physical training, 75% mental training

When compared for performance, Group 4 had the best outcomes of all four groups, and the less mental training a group practiced, the worse were their outcomes.[11] I am not sure I believe the claims of this legendary experiment, but I would like to believe them. I will suspend judgment until such time as the results can be verified and I can make a proper citation.

In 2012 Thomas Newmark made the claim that Russian research on Olympic athletes indicated that visualization techniques improved athletic performance in the 1984 Olympics.[12] Due to evidence from many other later studies it is clear that the more mental training one adds to one’s physical regimen (considering its quality, i.e., vividness, accuracy and relevance), the better performance one will achieve.

Mental practice can be a time-saving and cost-efficient method of simulation for training in certain occupations beyond sports, like dance, marksmanship or combat.[14] [15] [16] Scientific studies have shown that visualization has many of the same effects on the brain as physical activity. Studies have shown that while physical practice improves performance more than anything else, mental practice can enhance performance.[17]

Visualization practices help wire the brain for perception, motor control and memory, incidentally boosting confidence. Research on golf performance suggests that it is important to use visualization away from events that require present awareness, for example, between practices. Optimum performance is achieved when one uses an uninhibited state of awareness at the time of execution.[18] [19] Focusing the attention in the present moment during performance, a form of mindfulness meditation, is proven to increase chances of success.[20] [21] [22] [23]

Performance is enhanced by visualization through purely physical benefits as well as mental benefits. Scientific studies are showing that visualization by itself actually helps build muscle strength.[24] [25] [26] One study revealed a 13.5 percent improvement in strength in subjects who merely imagined maximum flexing of biceps.[27] [28] Of course, more muscle strength can be achieved with isometric training, where the muscle is contracted but without moving the joint, and the most expedient method of growing strength is by contracting muscles against resistance, such as weights.[29] [30]

Creative visualization can improve fitness in many ways. It can also affect your diet. Targeted mental imagery has been scientifically shown to improve success in achieving dietary goals. Periodically visualizing the steps of eating a piece of fruit seems to encourage eating more fruit, according to a study carried out in 2011 by Bärbel Knäuper, PhD. at McGill University.[31]

Diet, like exercise, affects health and many other aspects of life, like self-esteem, motivation, cognitive ability and relationships.[32] Visualization, too, can have an impact on these and other realms of life. It is not just athletes who can use visualization to achieve their life goals.

Life Goals

Everyone can achieve a higher quality of life by using visualization to help accomplish life goals. A study on golfers in 1995 observed how negative visualizations of a golf putt affected the performance of golfers. The study found that visualizations of negative outcomes resulted in a decline of accuracy.[1] This study, along with the storehouse of information on the beneficial effects of positive visualization, makes a convincing assertion that the way we visualize outcomes has a direct and significant impact on the results of our efforts in life.

Visualizations and accomplishments can be based on short-term actions or cultivated with long-term goals. Hollywood actors are taught special methods to breathe, visualize and act.[2] This allows them to better understand human behavior and control what they express to an audience. This kind of meditative visualization of one’s own character in the theatre of life can give anyone a safe place and time for self-reflection and planning. It can help form goals and offer inspiration how to achieve one’s goals.

A few simple methods define goal-achievement meditation. Choose one realistic and important short-term goal that you could accomplish within a couple of days.[3] Make sure the goal is significant to your life, rather than random or irrelevant to your goals in life, and make it something you can reasonably achieve.

Choose from any number of goals, for example, to get to bed on time, to study, to exercise, to get rid of your superfluous possessions, to stop eating beef by finding and making new recipes, to vote in upcoming elections for public office, to save $5000, to invest in some mutual funds, or to start a family. These goals can turn into long-term goals, but they begin as short-term, one day at a time.

Goals obviously possess different levels of difficulty, from easy tasks like cleaning a room, to starting a new career, to overcoming addiction. Visualizing the steps that lead to your goal being reached will make any undertaking easier. Begin by writing a list of the steps necessary to reaching your goal. In business this is called an action plan. For example, a blueprint for various goals might include:

- Write the action plan

- Visualization

- Make an appointment or schedule

- Dress appropriately

- Organize your tools

- First Step

- Second Step

- Third Step

- Etc.

- Goal completion

Once these steps are written down in a list, determine a time to practice these visualization techniques, such as early morning or in the evening before you sleep. Sit in a meditative posture, close your eyes and state your intent to achieve your goal. This is an affirmation of what you will to happen and your confidence in achieving your goal. Visualize each step being carried out, one at a time.

Holistic Imagery for Success

The most effective visualization uses a multi-sensory approach known as holistic imagery. Imagery is usually centered on visualization, that is, a visual picture within the mind’s eye. However, the more the senses are engaged, the more powerful the meditation becomes.[1] [2] [3] Imagery should include sights, sounds, smells, tactile feelings and kinesthetics.[4] More vivid imagery has a more profound effect on the mind.[5]

Imagine the environment at each step along the way toward your goal. Feel the emotions you will feel. Conjure the scents and the sounds as if you were there. Finally, create within the mind’s eye a detailed future scene of that goal being just accomplished. Imagine you are there in the moment. Evoke a strong positive emotional state to leave a powerful and productive impression.[6] Take a minute to return to the present moment and reaffirm your intention of fulfilling your goal.

Techniques for visualization will not work if you just read about them and think about them: these techniques must be actually carried out in reality. It does not take a lot of time and it costs nothing. There is evidence that vision and vision communication in business can result in venture growth.[7] Although we can discount claims of universal forces working on us via laws of visualization and success as pure pseudoscience, the consequences of vision and visualization in various business settings certainly deserves more research.

Visualization has been shown to play a unique part in physical and material accomplishments. Meditation with imagery is also useful in mental and spiritual endeavors. There are imagery techniques proven to be excellent solutions for studying and memorization. Visualization can be helpful in professional artistic creativity and science communication. Other methods have been used to induce spiritual experiences for enlightenment and the betterment of the personality.

Medically Reviewed by Dr. Andreas Laurencius, MD.

Read: The Science of Meditation, Happiness, and Enlightenment

Sources

Part 1: Creative Visualization

- Susan Heitler, PhD, “Advanced Visualization Techniques for Individual and Couples Therapy”, 29 Sept., 2017.

- “Mental image”, Wikipedia, accessed 24 Oct., 2018.

- “Creative visualization”, Wikipedia, accessed 24 Oct., 2018.

- Belleruth Naparstek, “Guided Imagery 101”, excerpted from Staying Well with Guided Imagery (1994) and Invisible Heroes (2005).

- Tracy C. Ekeocha, B.S., “The Effects Of Visualization & Guided Imagery In Sports Performance”, May 2015.

- “Research on meditation”, Wikipedia, accessed 24 Oct., 2018.

- Alvin Powell, “When science meets mindfulness”, The Harvard Gazette, 9 April, 2018.

- “Meditation: In Depth”, The National Institutes of Health (NIH), accessed 24 Oct., 2018.

Part 2: Guided Meditation

- Stephen M. Kosslyn:

https://psychology.fas.harvard.edu/people/stephen-m-kosslyn - “Creative visualization”, Wikipedia, accessed 24 Oct., 2018.

- E. Pickett, “Introduction,” in Guided Imagery and Music (Bruscia KE & Grocke DE, eds.), Barcelona Publishers, Gilsum, NH, 2002, pp. 15–25.

- M. Lin, M. Hsu, H. Chang, Y. Hsu, M. Chou, & P. Crawford, “Pivotal Moments and Changes in the Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music for Patients With Depression,” Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19 (2010), pp. 1139–1148.

- F. Goldberg, “The Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music,” in The Art & Science of Music Therapy: A Handbook (T. A. Wigram, B. Saperston, & R. West, eds.), Sydney, Australia: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1995, pp. 112–128.

- Emilie Pelletier, “4 Scientific Reasons Why Visualization Will Increase Your Chances to Succeed”, 24 Jan., 2018.

Part 3: Relaxation

- Julie Corliss, “Six relaxation techniques to reduce stress”, Harvard Health Publishing, Sept. 2016.

- Katherine Ellen Foley, “Science finally proves that meditation helps make your body markedly less stressed”, Quartz, 20 Feb., 2016.

- “Relaxation Techniques for Stress Relief”, PDF, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, retrieved 24 Oct., 2018.

- Lawrence Robinson, Robert Segal, M.A., Jeanne Segal, Ph.D., and Melinda Smith, M.A., “Relaxation Techniques: Using the Relaxation Response to Relieve Stress”, HelpGuide.org, Sept., 2018.

- Marilyn Mitchell, M.D., “Dr. Herbert Benson’s Relaxation Response”, Psychology Today, 29 March, 2013.

- MGH Public Affairs, “Mindfulness meditation and relaxation response affect brain differently”, The Harvard Gazette, 20 June, 2018.

Part 4: Health and Immunity

- Kathryn D. Kominars, PhD, “A Study of Visualization and Addiction Treatment”, Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, Volume 14, Issue 3, May–June 1997, pp. 213–223. (PDF)

- “Guided Imagery”, Wikipedia, accessed 24 Oct., 2018.

Part 5: Healing

- Leo, Pizarro, Gich, Barthe, Rovirosa, Farru, Casas, Arcusa, “A Randomized Trial of the Effect of Training in Relaxation and Guided Imagery Techniques in Improving Psychological and Quality-of-Life Indices for Gynecologic and Breast Brachytherapy Patients,” Psycho-Oncology, 16 (2007), pp. 971–979.

- Walker, Walker, Ogston, Heys, Ah-See, Miller, Eremin, “Psychological, Clinical and Pathological Effects of Relaxation Training and Guided Imagery During Primary Chemotherapy”, British Journal of Cancer, 80(1–2), 1999, pp. 262–268.

- Shapiro, Pisetsky, Crenshaw, Spainhour, Hamer, Dymek, Valentine, and Bulik, “Exploratory Study to Decrease Postprandial Anxiety: Just Relax!”, International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(8), 2008, pp. 728–733.

Part 6: Athletics

- Thelwell, R. C., & Greenlees, I. A. (2003). Developing Competitive Endurance Performance Using Mental Skills Training. The Sport Psychologist, 17(3), 318–337.

- Eddy, K. A. T., & Mellalieu, S. D. (2003). Mental Imagery in Athletes with Visual Impairments. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 20(4), 347–368.

- Epstein, M. L. (1980). The Relationship of Mental Imagery and Mental Rehearsal to Performance of a Motor Task. Journal of Sport Psychology, 2(3), 211–220.

- Hall, E. G., & Erffmeyer, E. S. (1983). The Effect of Visuo-Motor Behavior Rehearsal with Videotaped Modeling on Free Throw Accuracy of Intercollegiate Female Basketball Players. Journal of Sport Psychology, 5(3), 343–346.

- Richter, J., Gilbert, J. N., & Baldis, M. (2012). Maximizing Strength Training Performance Using Mental Imagery. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 34(5), 65–69.

- Druckman, D., & Swets, J. A. (Eds.). (1988). Enhancing Human Performance. National Academy Press.

- Oxendine, J. B. (1969). Effect of Mental and Physical Practice on the Learning of Three Motor Skills. Research Quarterly, 40(4), 755–763.

- Paivio, A. (1985). Cognitive and Motivational Functions of Imagery in Human Performance. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Sciences, 10(4), 225–285.

- Van Gyn, G. H., Wenger, H. A., & Gaul, C. A. (1990). Imagery as a Method of Enhancing Transfer from Training to Performance. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12, 366–375.

- Schmalbruch, S. (2015, January 28). Here’s The Trick Olympic Athletes Use To Achieve Their Goals. Business Insider.

- Christopher, L. (2018, October 24). The History, Science, and How-To of Visualization.

- Newmark, T. (2012, October 22). Cases in Visualization for Improved Athletic Performance. Psychiatric Annals, 42(10).

- Whetstone, T. S. (1995). Enhancing Psychomotor Skill Development Through the Use of Mental Practice.

- Robinson, A. (2018, May 6). A Dancer’s Introduction to Visualization.

- Cull, K. (2018, October 24). Visualization for Martial Arts: Get Better Without Training.

- Clark, L. V. (1960). Effect of Mental Practice on the Development of a Certain Motor Skill. Research Quarterly of the American Association for Health, Physical Education, & Recreation, 31, 560–569.

- Hebron, M. (2018, October 24). Visualization Hurting Golf Performance?. Golf Science Lab.

- MacKenzie, D. (2018, January 10). Visualization: The Most Powerful Thing in Golf.

- Sliwa, J. (2017, August 4). New Mindfulness Method Helps Coaches, Athletes Score. American Psychological Association.

- Chariton, C. (2018, October 24). Mindfulness: Improving Sports Performance & Reducing Sport Anxiety.

- Heckman, C. (2018, May 18). The Effect of Mindfulness and Meditation in Sports Performance. Kinesiology, Sport Studies, and Physical Education Synthesis Projects, 47.

- Adams, A. J. (2009, December 3). Seeing Is Believing: The Power of Visualization. Psychology Today.

- Ranganathan, V. K., Siemionow, V., Liu, J. Z., Sahgal, V., & Yue, G. H. (2004). From Mental Power to Muscle Power—Gaining Strength by Using the Mind. Neuropsychologia, 42(7), 944–956. PDF

- Mosher, C. (2014, December 23). How to Grow Stronger Without Lifting Weights. Scientific American.

- Clark, B. C., Mahato, N. K., Nakazawa, M., Law, T. D., & Thomas, J. S. (2014, December 15). The Power of the Mind: The Cortex as a Critical Determinant of Muscle Strength/Weakness. Journal of Neurophysiology.

- Ranganathan, V. K., Siemionow, V., Liu, J. Z., Sahgal, V., & Yue, G. H. (2004). From Mental Power to Muscle Power—Gaining Strength by Using the Mind. Neuropsychologia, 42(7), 944–956. PDF

- Ranganathan, V. K., Siemionow, V., Liu, J. Z., Sahgal, V., & Yue, G. H. (2004). From Mental Power to Muscle Power—Gaining Strength by Using the Mind. Neuropsychologia, 42(7), 944–956.

- Laskowski, E. R., M.D. (2018, October 24). Are Isometric Exercises a Good Way to Build Strength?. Mayo Clinic.

- Wedro, B., M.D., FACEP, FAAEM, & Weil, R., M.Ed., CDE. (2016, December 12). Anatomy and Physiology of Skeletal Muscles. MedicineNet.

- Knäuper, B., McCollam, A., Rosen-Brown, A., Lacaille, J., Kelso, E., & Roseman, M. (2011, February 18). Fruitful Plans: Adding Targeted Mental Imagery to Implementation Intentions Increases Fruit Consumption. Psychology & Health.

- Carson, T. L., Ph.D., Hidalgo, B., Ph.D., Ard, J. D., M.D., & Affuso, O., Ph.D., RD. (2013, October 30). Dietary Interventions and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior.

Part 7: Life Goals

- Woolfolk, R. L., Murphy, S. M., Gottesfeld, D., & Aitken, D. (1985). Effects of Mental Rehearsal of Task Motor Activity and Mental Depiction of Task Outcome on Motor Skill Performance. Journal of Sport Psychology, 7, 191–197.

- filmnutlive. (2010, April 14). Acting Coach Larry Moss [Video]. YouTube. Duration: 55:29.

- “Goal Visualization”, Greater Good in Action, UC Berkeley. Retrieved 24 Oct., 2018.

Part 8: Holistic Imagery for Success

- Andre, T., & Means, M. L. (1986). Rate of Imagery in Mental Practice: An Experimental Investigation. Journal of Sport Psychology, 8, 124–128.

- Paivio, A. (1985). Cognitive and Motivational Functions of Imagery in Human Performance. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Sciences, 10(4), 225–285.

- Denis, M. (1985). Visual Imagery and the Use of Mental Practice in the Development of Motor Skills. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Sciences, 10(4), 45–165.

- Farah, M. J., Hammond, K. M., Levine, D. N., & Calvanio, R. (1988). Visual and Spatial Mental Imagery: Dissociable Systems of Representation. Cognitive Psychology, 20, 439–462.

- Ryan, E. D., & Simons, J. (1982). Efficacy of Mental Imagery in Enhancing Mental Rehearsal of Motor Skills. Journal of Sport Psychology, 4, 41–51.

- Adams, A. J., MAPP. (2009, December 3). Seeing Is Believing: The Power of Visualization. Psychology Today.

- Baum, R. J., Locke, E. A., & Kirkpatrick, S. A. (1998). A Longitudinal Study of the Relation of Vision and Vision Communication to Venture Growth in Entrepreneurial Firms. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(1), 43–54.