Tantric Cosmology

Tantric Yoga is one of the most misunderstood and yet profoundly transformative streams of Indian spiritual practice. Often misrepresented in the modern West as little more than sacred sexuality, the true essence of Tantra is far older, deeper, and more intricate.

Rooted in ancient Indian texts and esoteric traditions, Tantric Yoga weaves together ritual, breath, visualization, mantra, and energy work to awaken the latent powers of consciousness. It does not seek escape from the world but rather embraces the body, the senses, and the material realm as sacred vehicles for liberation. This article explores the origins, philosophy, and practices of Tantric Yoga, shedding light on its spiritual depth and its vision of unity between the mundane and the divine.

Tantric Yoga, developed in the sixteenth century CE, seems particularly concerned with anatomy, which is largely spiritual. Tantra applies the three gunas to energy, as causal, subtle, and gross, and to man, as sat, will (or transcendental consciousness), chit, knowledge (or mind), and ananda, action (or matter.) These three qualities are symbolized respectively, as sun, fire (the underlying element of the universe), and moon.

The causal, subtle, and gross levels of existence are, respectively, the causal forces that exist eternally and immutably, the subtle architecture of the whole of existence, and the gross elements of nature. Human existence on these planes is defined as bindu, nada and bija or will, knowledge and action. The triune concepts of idea, word (logos) and action of Classical Greek philosophy run parallel to the tantric model.

The tantrist imagined that the god Shiva was the essence of being, formless and unchanging truth. He was consciousness and bliss who desired manifestation, and thus, as first cause, created the universe, illusion (maya), a contraction within the pure and perfect self. When Shiva’s third eye opens, the universe will be destroyed.

The tantrist’s goal is transcendence of maya, supreme consciousness, the dissolution of self in other. The god manifested as thirty-six kinds of energy, or tattvas, which include aether, air, fire, water, and earth; anatomy and bodily functions, the senses, and four states of consciousness.

The Chakras and Kundalini

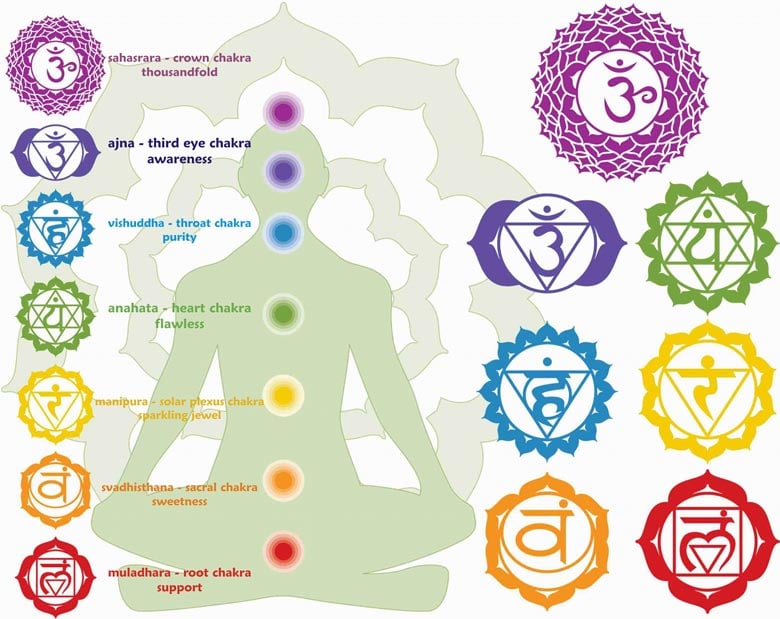

Each kind of energy is contained in a number of central locations called chakras, or disks, along the spine of the human being. Chakras may number seven, eight, or more, depending on the source of information. Prana, vital energy or life-force, manifests through the breath. The chakras are centers of prana, as fourteen principle nadis are channels of prana. The prana of Shiva is causal, the chakras and nadis are subtle, and nerves and blood vessels are gross.

The Shiva Samhita and other traditional sources describe the chakras as the yogi is meant to visualize them during meditation. There are many websites found with a quick search on a search engine like Google that explain the chakras and associated sounds and visualizations for beginners (like this one). The seven chakras are associated with specific symbols, flower petal numbers, colors, sounds, gods and physical elements:

Sahasrara, crown chakra located at the crown of the head – self-realization

Ajna, guru or third-eye chakra located between and slightly above the eyebrows – non-duality

Vishuddha, throat chakra located at the base of the throat – space or aether (akasha)

Anahata, heart chakra located in the heart – air

Manipura, solar plexus or navel chakra located in the abdominal region – fire

Svadhishthana, sacral chakra located at the root of the reproductive organ – water

Muladhara, root chakra located at the base of the spine – the element of earth

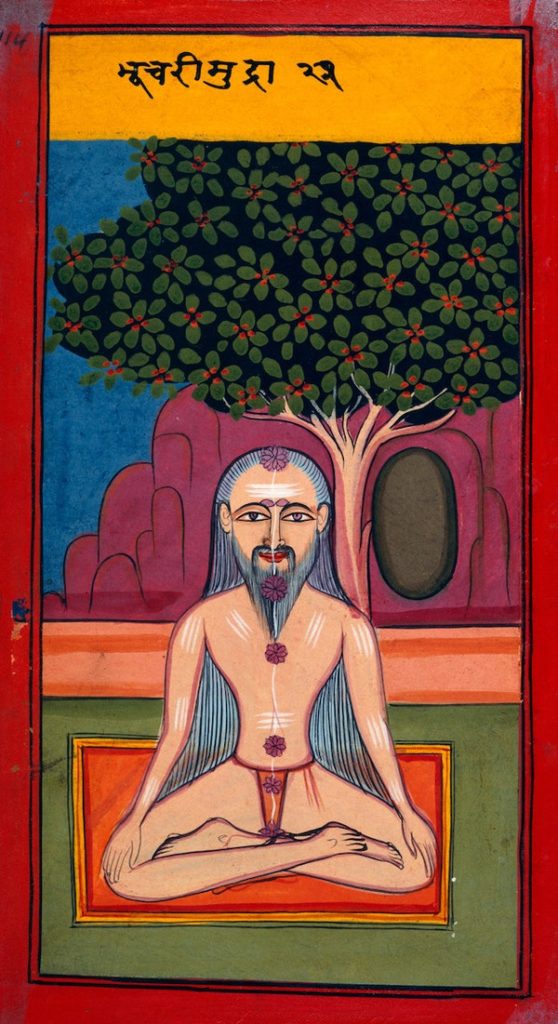

The three chief nadis are the central susumna, the “feminine” or “moon” ida to the left, and the “masculine” or “sun” pingala to the right. The nadis begin at Muladhara, the “root-support” chakra at the base of the spine, and meet at Ajna, the chakra at the yogin’s “third eye.” At the base of the spine is where the “coiled serpent” of Kundalini energy rests.

Kundalini is the energy of consciousness which is created when prana is transformed through tantric meditation. Breathing techniques purify the nadis and the chakras. Similar to monastic chanting, mantra, the ritual repetition of sounds, words, or phrases, is used to raise the Kundalini to open the “third eye” chakra of the yogin.

The Early Tantric Literature

The first mention of the seven chakras is provided in the Vedas. The Rig Veda Mandala Eight, Hymn 28, Verse 5 may be interpreted as a reference to the chakras:

- THE Thirty Gods and Three besides, whose seat hath been the sacred grass,

From time of old have found and gained.

- Varuna, Mitra, Aryaman, Agnis, with Consorts, sending boons,

To whom our hymn is addressed:

- These are our guardians in the west, and northward here, and in the south,

And on the east, with all the tribe.

- Even as the Gods desire so verily shall it be. None ‘minisheth this power of theirs,

No demon, and no mortal.

- The Seven (gods) carry seven spears; seven are the splendours they possess,

And seven the glories they assume.

(From The Rig Veda (1896), translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith.)

The chakras appear in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, written some centuries before the 4th century CE. There are twenty Yoga Upanishads in the Vedas, composed after the Yoga Sutras. Early Yoga Upanishad texts that describe the chakras include the Darshana Upanishad, the Yogashikha Upanishad and the Shandilya Upanishad.

Written in the tenth century, the Sat-Cakra-Nirupana, and the Padaka-Pancaka, translated in 1919 by John Woodroffe in The Serpent Power: The Secrets of Tantric and Shaktic Yoga, and the Gorakshashatakam, are guides to meditating on the chakras.

The fifteenth century classic Hatha Yoga Pradipika[1] tells that Shiva is the divine patron of Hatha Yoga, a science belonging to Raja Yoga, or Royal Yoga, the Astanga or Classical yoga. Shakti, the consort of Shiva, bestows her wisdom and power upon the yogin who cycles life-force up and down the spine and concentrates on the Absolute.

This science of postures and visualizations was meant to be kept secret and passed along from guru to disciple. Once the yogin is adequately trained by the guru, he is to begin his endeavors in a secluded, well kept hut, situated in a peaceful and affluent location. The yogin is to eat moderately, socialize little and conserve energy.

The supreme posture is Siddhasana, sitting in half lotus position, chin on chest, looking steadily at the third eye. In Hatha Yoga the sun and the moon are symbols for various opposites, for example, in the alchemical union of the three channels of life-force upon the spine, Pingala– sun, Ida– moon and Shusumna– fire.

The union of opposites upon inhale results in youth, immortality even, and a death-like state of meditation even before the exhale. The alchemical elixir is called soma, essence, nectar, or liquor, and falls from the top of the head to shower the yogin’s spiritual anatomy in the panacea of the alchemical operation.

Later Tantric Literature

Written in the fifteenth or sixteenth century by an anonymous author, the Shiva Samhita, or Corpus of Shiva, is one of the three great works on Hatha Yoga, with the Gheranda Samhita and the Hatha Yoga Pradipika. It is a work of physiology and visualization of a spiritual anatomy.

The later Yoga Upanishads written in the 15th and 16th centuries also mention the chakras and their locations. The early practical guide on yoga and Kundalini, the Yogatattva Upanishad, describes early tantric anatomy and technique to meditate upon the chakras to attain Samadhi. The Yogakundalini Upanishad, as is evident by its name, is a fundamental treatise on Kundalini Yoga.

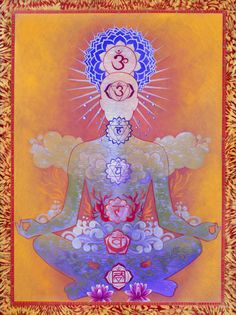

The locations of the familiar seven chakras or psychic wheels of Indian Kundalini yoga serve well as foci for concentration in visualization. These are explained as spiritual nerve centers as such, along the middle channel of three psychic channels down the length of the spine, which branch out into networks of smaller psychic nerves throughout the human anatomy. The relative cumulative effects on the brain and quality of life of this construct and alternative constructs should be the subjects of active scientific observation.

Where the chakras are described in the Shiva Samhita, the seventeenth century hatha yoga classic, so are described the three gunas or qualities sattva, rajas and tamas, the forces of harmony, energy and gross matter/inertia. These are identified symbolically with fire, the sun and the moon.

The elixir of immortality is said to flow continuously from the highest chakra, the thousand-petalled Sahasrara at the top of the skull. Every student of Ayurveda, traditional Indian medicine, is familiar with the chakras and the gunas.

[1] Akers, Brian Dana. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Original Sanskrit Svatmarama, An English Translation Brian Dana Akers. YogaVidya.com LLC. 2002.

Tantric Meditation

Following the advice of the classic texts, tantric yoga begins with finding a quiet, natural and peaceful environment. The yogin is to eat moderately, socialize little and conserve energy. The supreme posture is Siddhasana, sitting in half lotus position, with one foot over the opposite thigh, chin on chest, looking steadily at the third eye. Padmasana, also known as Full Lotus, with both feet resting on the opposite thigh, is also traditional.

Prana in Sanskrit implies variously the breath, the breath of life, energy, spirit and life-force. Pranayama is the regulation of the breath or life-force by breathing exercises, which is one of the eight limbs of Ashtanga Yoga advanced by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras. Pranayama, a method of relaxation, is preliminary to concentration practiced to induce Samadhi, the meditative trance of mystical oneness.

Several forms of pranayama are basic exercises of Hatha Yoga, for example, the popular Nadi Shodhana (“channel purification”) Pranayama, or alternate nostril breathing. This practice is done by sitting in asana with a straight spine, left hand resting on the left knee, either open or in the Dhyana (Jhana or Chin) mudra hand position.

A mudra is a symbolic ritual gesture, usually with the hands, in Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as Indian classical dance. The Dhyana mudra joins the tip of the thumb and forefinger, extending the other fingers in a soft arc, with palm facing upward.

Place the tips of the index and middle fingers of the right hand between the eyes, rest the thumb on the right nostril of the nose, and rest the ring and little finger on the left nostril.

Close the right nostril with the thumb and exhale out of the left nostril.

Take a gentle pause, then inhale deeply through the left nostril.

Release the right nostril and close the left nostril with the ring finger, exhaling through the right nostril.

Inhale through the right nostril and then close it with the thumb, releasing the left nostril to exhale through it.

This is one complete cycle of the alternate nostril breath.

The Science of Tantric Meditation

Scientific studies have shown several benefits of pranayama. Benefits include decreased anxiety and depression, cardiovascular improvement, and pain reduction.[1] Basic Hatha Yoga techniques can also improve physical fitness, temper conditions related to obesity and diabetics, and increase the quality of life of cancer patients.[2]

Kundalini yoga has been shown to have a marked positive effect on memory and other cognitive functioning of older adults.[3] In fact, meditation is one of the best habits to maintain and improve cognitive functioning.[4]

Meditating Kundalini and the chakras begins with asana (posture) and pranayama (controlled breathing). The Hatha Yoga Pradipika recommends assuming the Padmasana posture, or Lotus Pose, and practicing the alternate nostril breath, holding each breath for as long as possible.

Prana is to be visualized as the serpent Kundalini awakening, rising from the base of the spine and circulating through the nadis, the psychic channels, primarily the two main channels, Ida and Pingala.

Ida and Pingala originate at the left and right side of the base of the spine and the central nadi, Sushumna, respectively. They spiral around Sushumna like the serpents around the caduceus, crossing at each chakra, and end in the left and right nostrils just as they originated at the base of the spine.

The whole visualization amounts to a total body scan. The discipline is to complete eighty cycles four times daily; morning, noon, evening and midnight. This is imagined to purify the channels.[5]

Tantric Yoga is well known for prescribing practices for meditation during sexual intercourse. The theory is that the retention of semen helps preserves a man’s energy. The woman, however, is energized by combining the male reproductive fluid with her own within her body. The science, perhaps unsurprisingly, does not bear this out.

There is no science to establish that the chakras or nadis have any basis in physical reality, except perhaps the obvious correspondence of the chakras and central nadi with the spine, and the loose identification of the ajna (third eye) chakra with the pineal gland. This spiritual anatomy must therefore be assumed to be largely a mental construct until such time that clinical studies provide evidence otherwise.

While these visualizations and cognitive exercises are certainly of value, it should be remembered that the ultimate goal remains to practice mindfulness meditation and cultivate that state of mind called Samadhi, the absorption of the mind in meditative concentration.

Learn more about Samadhi and other states of meditation in:

The Science of Meditation, Happiness, and Enlightenment

Sources

-

Mollet, J. (2015, November 22). What Science Has to Say About Pranayama. Elephant Journal.

-

Sengupta, P. (2012, July). Health Impacts of Yoga and Pranayama: A State-of-the-Art Review. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 3(7), 444–458.

-

Watts, V. (2016, May 3). Kundalini Yoga Found to Enhance Cognitive Functioning in Older Adults. Psychiatric News.

-

Bergland, C. (2014, March 12). Eight Habits That Improve Cognitive Function. Psychology Today.

-

Quistgard, N. (2007, August 28). Balancing Act. Yoga Journal.