Updated 2025 |

Qigong: Working with Qi

Qigong (Ch’i Kung), which means “work with Qi,” is the art of mastering Qi or life-force and discovering the “inner medicine” to sustain heath and balance.

Although the practice hails from 4000-year-old traditional Chinese medicine, the word “Qigong” originates in Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 CE) Daoism.

The word “gong” (“kung”) is well known from the Chinese martial arts, which are called wushu (“wu” means martial; “shu” means art) or gongfu (kung fu), a term that implies hard work of any kind.

Qigong has traditionally been practiced with Chinese martial arts. This is an optimal way to utilize the benefits of Qigong. All Chinese martial arts derive from Shaolin boxing (quan). The Shaolin Temple Chan Buddhist monks originated the body-strengthening and self-defense exercises known as gongfu.

Like the Shaolin Temple monks, Wudang Mountain Daoist monks developed martial arts based on Qi circulation exercises. Taijiquan (Tai Chi Chuan), based on yin-yang philosophy; xing yi quan, (Hsing I Chuan) based on the five elements theory; bagua quan (Pa Gua Chuan), based on the eight trigrams theory; and Wudang Gongfu are the styles of Wushu developed by the Daoist monks of Wudang Shan in Hubei.

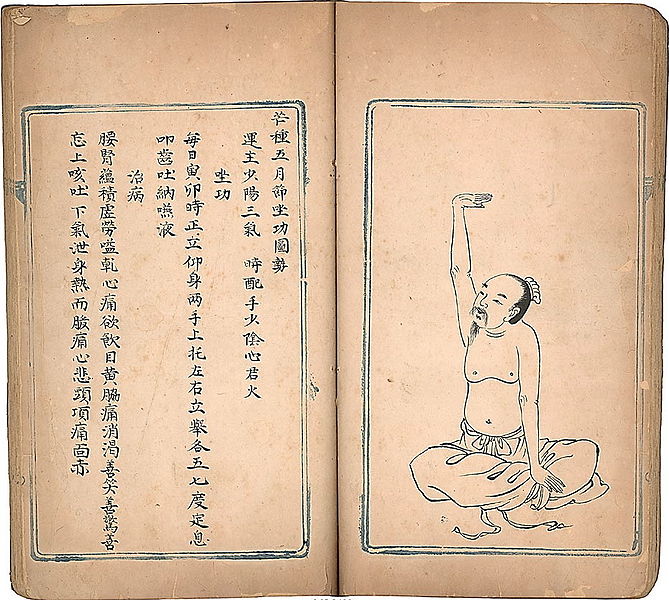

There are several types of Qigong: Daoist, Buddhist, Confucian, martial art, and medical Qigong. In ancient times simple focused breathing was practiced by Daoists as Tu-Na, “expel and receive.” One form of Qigong is Neigong, a breathing, visualization and movement exercise.

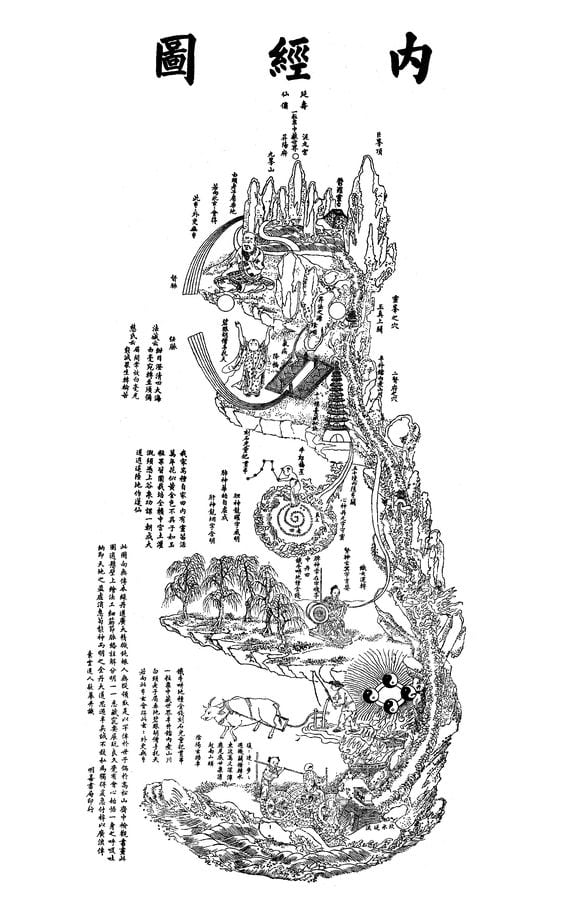

Neigong is best known for its place in “internal” or “soft style” martial arts, such as Taijiquan, Baguazhang and Xingyiquan, as opposed to the “external” or “hard style” of Shaolin boxing. An example of Neigong is the silk reeling exercise of the Wu and Chen styles of taijiquan. Wudang Daoists say that “Qigong” is the first stage of practice in Neidan, or Daoist internal alchemy, a system of meditation.

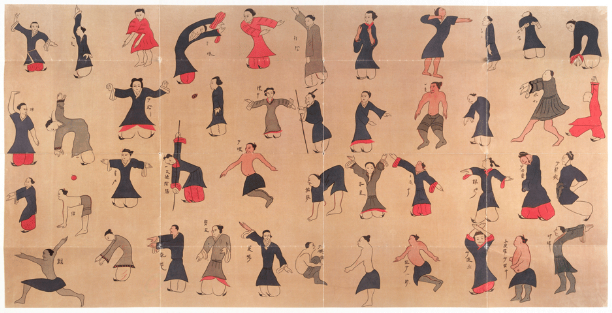

Daoyin (Tao Yin) is a non-martial form of Neigong exercise for the circulation of Qi and blood, a combination of neuro-muscular stretching, massage, breathing exercises, and meditation. Daoyin is an ancient exercise that predates Qigong as a therapeutic system of cultivating Qi.

Daoyin was developed by monks in Chinese Daoist monasteries since at least the Warring States period (475 – 221 BCE), and Qi cultivation exercises likely existed centuries before this time. Traditional Chinese Medicine assigns the origin of Qigong to the legendary Yellow Emperor (2696–2598 BCE) and the classic of medicine attributed to him, the Huangdi Neijing.

It has been shown that the earliest instructions on meditation in China, including the Warring States Era (around 400 BCE) Xingqi Jade Inscription, the fourth century BCE work titled Neiye, and the famous Laozi, itself, all described regulation of Qi. As mentioned, “Xingqi” means “Circulating Qi,” and refers to the title of the jade inscription.

The Neiye was a short manual on breath and qi meditation, now believed to be the oldest mystical text in China.[1] It introduced to traditional Chinese medicine and Daoist internal alchemy (Neidan) the concept of the Three Treasures: essence (jing), life-force (qi) and spirit (shen), and influenced the Laozi and the Zhuangzi.

The Laozi did not mention Qigong exercises, but rather, introduced a policy of non-action (wu-wei) and making the breath soft. The Zhuangzi taught moral uprightness and meditation; however, it discouraged Qigong exercises as “panting” and “puffing” for longevity.

Daoist religion developed along the principles of Laozi and Zhuangzi even as it continued to produce Qigong exercises and meditations involving the movement of Qi. Daoist monks on Mount Wudang incorporated Qigong into their martial arts.

Confucians, following Mencius, viewed the cultivation of Qi as moral development. As mentioned above, Mencius developed his xin, or heart-mind, for physical, mental, moral and spiritual purposes. His system involved the Confucian way of life that included exercises to cultivate qi (life-force). Nourishing qi meant right behavior (yi) in alignment with the Dao (2A2 & 6A7-8).[2]

Neo-Confucianism developed its own style of meditation in the Song dynasty, Jing Zuo, “quiet sitting” or “sitting in silence” for health or spiritual cultivation. Qigong may be practiced during jingzou.

[1] Graham, A. C. (1989), Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China, Open Court.

[2] Jeffrey Richey, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

“Mencius” (8. Moral Psychology), retrieved Jan. 1, 2022, https://www.iep.utm.edu/mencius/

Origins of Qigong

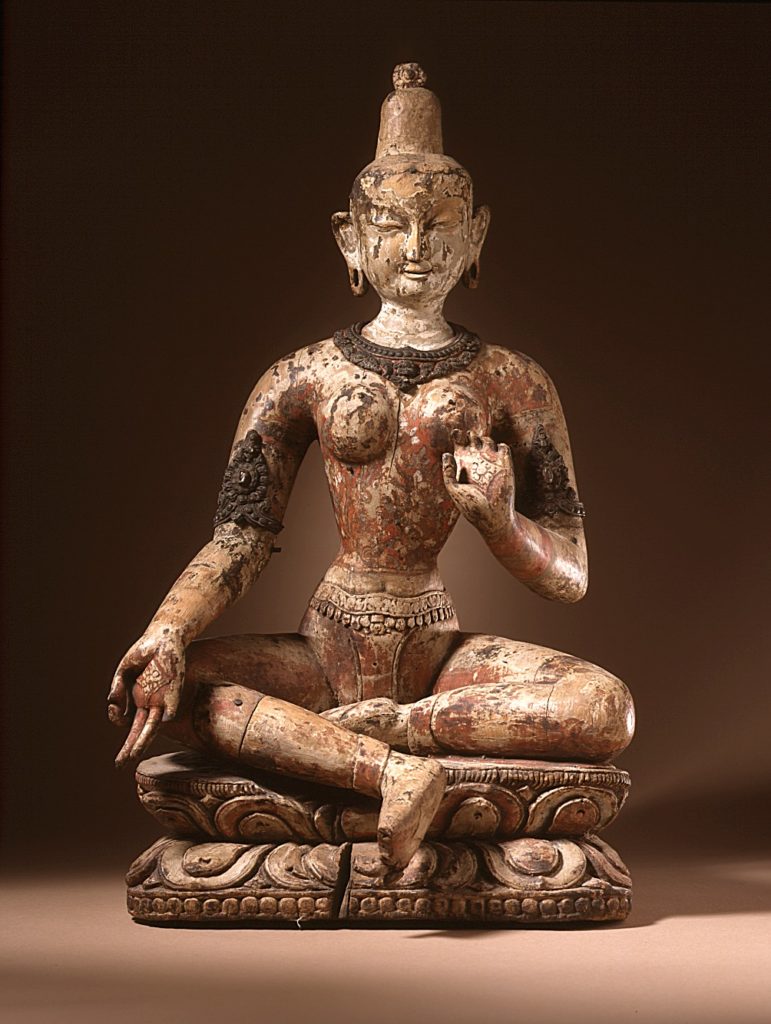

Indian yogic techniques centered on the concept of attaining enlightenment through cultivating prana, the equivalent of Qi. Buddhism brought some of these Hindu yogic practices to China, where they may properly be termed Qigong.

Chinese Buddhism found its ultimate expression in Chan (“Meditation”) Buddhism, first taught by the Six Patriarchs of China during the Tang Dynasty. The first Patriarch of Chan was an Indian named Bodhidharma, also known as DaMo, who is claimed to have been the 28th Patriarch of Buddhism in a lineage from Gautama Buddha.

As the founder of Chan Buddhism, Bodhidharma was also credited with introducing tea consumption to China as a stimulant for monks during zazen, and teaching boxing at Shaolin temple. Chinese martial arts existed long before the monks at the Shaolin monastery began training in wushu, as evidenced by mentions of wrestling, hard techniques and soft techniques in the Chinese classics.

Shaolin is named for Mount Shaoshi, one of seven mountains that form the Songshan mountain range. According to legend, the Shaolin temple was constructed in Henan Province in 495 CE around an Indian monk named Buddhabhadra, a.k.a. Batuo, and his two Chinese disciples Huiguang and Sengchou. These two monks were known martial artists.

Bodhidharma arrived at the Shaolin temple in 527 CE and is said to have meditated facing the wall in a nearby cave for nine years. The legend goes that he refused to teach until, after weeks of keeping vigil in the snow, Dazu Huike cut off his own arm as a show of dedication.

Huike was given a robe, a bowl and a scroll of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra along with the transmission of the Dharma. He became the first Chinese-born Patriarch of Chan Buddhism. Huike, like Huiguang and Sengchou, was a martial artist.

Two classics of Qigong exercise are traditionally falsely attributed to Bodhidharma, most likely written in the 17th – 19th century, the Yi Jin Jing (Muscle and Tendon Changing Classic) and the Xi Sui Jing (Marrow and Brain Washing Classic). These works are used at the Shaolin temple to teach Qigong and gong fu. One can view the Shaolin Change Tendon and Wash Marrow Gong Fu on video via You-Tube.

The martial arts styles Hung Gar and Wing Chun maintain the legend that Bodhidharma developed the Twelve Posture Moving Exercise or “Twelve Fists of Bodhidharma” based on observations of twelve animals. However, there are no early sources for the books traditionally attributed to Bodhidharma.

In 1858 Pan Weiru wrote the “Essential Techniques for Guarding Life,” which described the Twelve Posture exercises in the Muscle and Tendon Changing Classic. In 1882 Wang Zuyuan published the “Internal Techniques Illustrated” with the same methods to strengthen muscles and tendons with Qi cultivation.

Styles of Qigong and Qi Science

The Luohan quan or “Arhat fist,” named for Buddhists who have been enlightened, is the oldest style of gong fu practiced at the Shaolin temple. It was created by Shaolin monks during the Sui dynasty (581 – 618 CE) and has been passed down in various lineages through the generations. “Luohan” is an over-arching term for all Shaolin boxing as well as many styles within the Shaolin system. The several Shaolin Luohan Eighteen Hands are considered the roots of the Shaolin styles of gong fu.

Shaolin Luohan Techniques Taught by a Shaolin Monk

There are countless Qigong and martial arts forms in the numerous styles of gong fu. Shaolin gong fu is the oldest and largest extant school of gong fu and encompasses hundreds of different styles and over a thousand various forms that have survived to this day. One of the oldest Shaolin gong fu forms is the Seven Star Fist.

The Chinese Health Qigong Association has officially recognized these Buddhist and Daoist health qigong forms from traditional practices: Muscle-Tendon Change Classic (Yì Jīn Jīng), Five Animals (Wu Qin Xi), Six Healing Sounds (Liu Zi Jue), Eight Pieces of Brocade (Ba Duan Jin), Tai Chi Yang Sheng Zhang, Shi Er Duan Jin, Daoyin Yang Sheng Gong Shi Er Fa, Mawangdui Daoyin and Da Wu.

For those who wish to investigate further, there are these other well-known styles of Qigong: Soaring Crane Qigong, Wisdom Healing Qigong, Pan Gu Mystical Qigong, Wild Goose (Dayan) Qigong, Dragon and Tiger Qigong, Primordial Qigong (Wujigong) and Chilel Qigong.

Scientific experimental evidence does not suggest the existence of Qi (life-force) as a tangible thing. More studies need to be done on Qi practices before a thorough understanding of the concept can be formed.[1] [2] [3] The concept of life-force may be nothing more than a mental construct to account for various essential elements of a healthy and enlightened life or state of mind. [4]

The traditional Chinese methods of diagnosis and prognosis according to the relationships of constitution, organs, channels, pulses, the seasons, emotions, Qis, and “pathogenic wind,” as used in acupuncture, are not scientifically valid. [5] [6] However, there are concrete health benefits to Qigong practice and other Qi-related modalities. [7] [8] [9]

Article continues after Notes

Notes

[1] NMJ Contributors, “An Evidence-based Review of Qi Gong

by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration,”

Natural Medicine Journal, Vol. 2, Issue 5, May 2010,

naturalmedicinejournal.com/2010-05/evidence-based-

review-qi-gong-natural-standard-research-collaboration

[2] James Flowers, “What is Qi?”

Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine :

eCAM, 2006 Dec; 3(4): 551–552,

published online Oct 23, 2006,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1697751/

[3] Paul Ingraham, “Do You Believe in Qi? How to embrace a central concept

of Eastern mysticism without being a flake,” Painscience.com, 2009,

https://www.painscience.com/articles/do-you-believe-in-qi.php

[4] Wallace Sampson and Barry L. Beyerstein,

“Traditional Medicine and Pseudoscience in China:

A Report of the Second CSICOP Delegation (Part 2),” CSICOP.org,

Volume 20.5, September / October, 1996

https://web.archive.org/web/20091105174459/http:

//www.csicop.org:80/si/show/china_conference_2

[5] Joe Fulgham, “Acupuncture,” Science-Based Medicine, retrieved Dec. 18, 2021,

https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/reference/acupuncture/

[6] Victoria Stern, “5 Scientists Weigh in on Acupuncture,” Scientific American, July 1, 2014,

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/5-scientists-weigh-in-on-acupuncture/

[7] Roger Jahnke, OMD, Linda Larkey, PhD, Carol Rogers, Jennifer Etnier, PhD, and Fang Lin,

“A Comprehensive Review of Health Benefits of Qigong and Tai Chi,” Am J Health Promot.

Author manuscript; available in PMC July, 2011,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3085832/

[8] Tima Vlasto, “Why Acupuncture Works – New Scientific Breakthrough,”

American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, March 24, 2010,

https://www.actcm.edu/blog/acupuncture/new-

scientific-breakthrough-proves-why-acupuncture-works/

[9] NCCIH, “Acupuncture: In Depth,” NCCIH.NIH.gov, Jan., 2016,

https://nccih.nih.gov/health/acupuncture/introduction

Qigong for Health

Qigong is a meditative practice that can be done sitting still, standing in a motionless posture, or with proper movements. Daoist alchemists use various breathing exercises, chanting, music, visualization and ritual to cultivate Qi. An example of sitting Qigong may be found in this article: “Chinese Daoist Alchemical Meditation.”

Certain taijiquan postures are used for standing stationary meditation, such as “Beginning Posture,” “Single Whip,” “Lift Hands” and “Holding a Jug.” The Eight Pieces of Brocade (Baduanjin qigong) is an ancient Chinese form consisting of motionless postures.

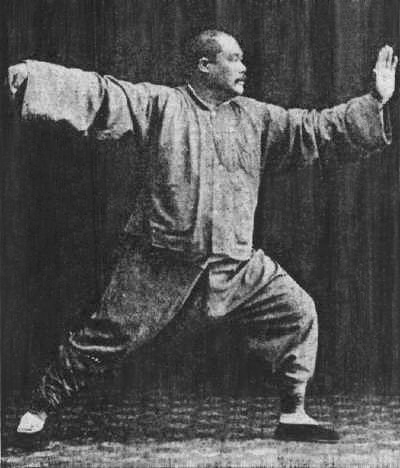

Most Qigong involves movement. Every action is coordinated with the breath and the mind in a practiced routine. The Daoist Taijiquan (Grand Ultimate Style), Xingyiquan (Five Elements Style) and Baguaquan (Eight Trigrams Style) forms are all Qigong in motion. These must be learned from a teacher.

Qigong can be a body scan meditation, a form of mindfulness meditation where the various parts of the body are systematically sensed, visualized and relaxed. Scientific studies have shown that the body scan can increase pain tolerance and reduce subjective pain ratings in people with chronic pain, as well as lessen fatigue, stress, anxiety and depression, according to self-reporting.

The body scan with intentional acceptance of pain is more effective at pain reduction than relaxation or distraction methods. However, it has no significant effect a visual analogue scale, heart rate or skin conductance response measures, i.e., the nociceptive system and autonomic nervous system.[1]

Qigong can be a form of calisthenics, a form of physical exercise using mainly body weight to improve flexibility, strength and fitness, commonly practiced in sports and the military. Some popular callisthenic exercises are push-ups, squats, lunges, dips and planks, among others.[2] [3] Qigong is best for the mind and body when it is callisthenic and aerobic, that is, when it strengthens the muscles and exercises the cardio-vascular system.

Calisthenics has been shown to have many benefits, including working several muscle groups at once for a natural build, burning calories better than many aerobic workouts, building endurance, increasing resting heart rate, helping flexibility, improving balance and coordination and boosting self-esteem. Calisthenics has a lower risk for injury than weight machines and aligns joints rather than stressing them.[4]

Ancient theories about Qigong as a type of subtle energy may not hold water, but some more modern theories of Qigong as a measure of various aspects of health seem to hold up under scientific scrutiny. Qigong practices have been shown to have health benefits. Qigong is also useful as a healthy preparation for motionless mindfulness meditation. Proper forms of Qigong are certainly recommended as part of a holistic lifestyle.

Article continues after Notes

Notes

[1] Neil Bossenger, Supervisors: Gwyn Lewis, PhD, Alice Theadom, PhD,

Immediate Effects of a Brief Mindfulness Body Scan Meditation

on the Nociceptive and Autonomic Nervous Systems,

a thesis submitted to AUT University, School of Rehabilitation & Occupational Studies,

Faculty of Health & Environmental Studies, September 2015,

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f6aa/6eeee95ccaf32a0010569278455d97a75270.pdf

[2] Pete Williams, “The Beginner’s Guide to Calisthenics,” Men’s Journal, Retrieved Dec. 18, 2021,

https://www.mensjournal.com/health-fitness/beginners-guide-calisthenics/

[3] Stew Smith, “Avoid the Gym by Using Calisthenics,” Military.com, Retrieved Dec. 18, 2021,

https://www.military.com/military-fitness/workouts/avoid-gym-by-using-calisthenics

[4] Health Fitness Revolution, “The Effects Of Calisthenics On The Body,”

healthfitnessrevolution.com, July 13, 2016,

http://www.healthfitnessrevolution.com/the-effects-of-calisthenics-on-the-body/

Wudang Daoist Wushu

All Chinese martial arts, which are called wushu, derive from Shaolin boxing (quan), popularly known as Shaolin “Kung Fu” (gongfu) from the Shaolin Temple Chan Buddhist monks who originated the body-strengthening and self-defense exercises. Like the Shaolin Temple monks, Wudang Mountain Daoist monks have developed martial arts based on Qi circulation exercises.

Tai Chi Chuan (taijiquan), based on yin-yang philosophy; Hsing I Chuan (xing yi quan), based on the five elements theory; Pa Gua Chuan (bagua quan), based on the eight trigrams theory; and Wudang Kung Fu are the styles of Wushu developed by the Daoist monks of Wudang Shan in Hubei.

Mount Wudang in Hubei region, China, developed its own unique style of alchemical military magic Daoism. The monks of Mount Wudang especially venerated the warrior god Zhenwu (True Warrior) or Xuanwu (Dark/Mysterious Warrior), symbolized by the serpent wrapped around the tortoise.

The Pole Star Sect developed a system of esoteric Daoism or magic ritual that includes precise steps upon a pattern based on the seven stars of the constellation called the Northern Dipper, also known as the Northern Bushel, the Big Dipper, and Ursa Major. Traditional mudras or “hand seals” are made with magical incantations and visualizations. Magical charts and talismans are created for ritual purposes.

Early Daoist internal martial arts, or long fist, began with the thirty-seven movements Sān Shí Qī style of the Tang Dynasty (618-905) hermit Hsa Suan Ming, in the mountains of Anhui Province. The movements were based on Yijing philosophy and strung together as a form. Jou, Tsung Hwa in his book The Tao of Tai-Chi Chuan, Way to Rejuvenation[1], notes three other examples of long fists that existed previously to taijiquan.

The first taijiquan proper first appeared with the Chen family in a village at the base of Mount Wudang, but later taijiquan masters of the Yang style associated the origins of their art with the legendary Zhang San Feng.

Most of the Zhang San Feng legend is myth, such as the belief that he lived to be 200 years old, living through the Sung, Yuan and Ming Dynasties. According to tradition, he was born on midnight of April 9, 1247, a day that is still celebrated by taijiquan players. He is said to have died in 1447.

One theory holds that there were two Zhang San Fengs who lived on Mount Wudang, one who lived 960 – 1279 and another who lived 1279 – 1368. It is very likely that several daoists chose to adopt the name Zhang San Feng after the legendary sage.

[1] Jou, Tsung Hwa, The Tao of Tai-Chi Chuan, Way to Rejuvenation,

Tai Chi Foundation, Warwick, NY, 1991, pp. 9 – 10.

Zhang San Feng and Chen Style Taijiquan

The famous Zhang San Feng was a Daoist priest who was born on or near Dragon-Tiger Mountain, lived on Ge Hong Mountain and Hua Mountain, studied at the Shaolin Temple, retired on Mount Wudang and became a Xian, a Daoist enlightened immortal.

Like the Greek Cincinnatus admired by George Washington and other Western luminaries, Zhang San Feng was a gifted young man from a prominent family, eligible for high office but preferring to live simply and closer to nature, without great wealth or honors. He is said to have avoided serving two emperors.

The legend goes that Zhang San Feng was at home on Mount Wudang and noticed a flock of birds watching a fight on the ground between a magpie and a serpent. The serpent moved in circles as the magpie flew up and down and side to side. The bird and the serpent disappeared when Zhang San Feng stepped outside. He realized that softness was superior to firmness in a fight and thus invented taijiquan.

A different version of the legend states that the serpent stayed still and would strike quickly, until it finally did kill the bird. Another story claims that Zhang San Feng first saw taijiquan in a dream. His new 72-movement boxing style was based on Shaolin gongfu, Daoist Qigong and the teachings of the Book of Changes, or Yi Jing (I Ching).

Modern scholarship has found that Taijiquan was actually invented by the Chen family, who were known for their martial arts. The family occupied Chen Village (Chenjiagou) at the base of Mount Wudang in Henan Province from the thirteenth century.

In seventeenth century Ming Dynasty soldier Chen Wangting (1580–1660 CE) arranged seven routines from the Chen family martial arts regime. Five routines were taijiquan, one was a 107 movements long fist, and the last was a speed punching method known as Cannon Fist.

In 1670 Huang Zongxi claimed in Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan that Zhang San-Feng invented internal martial arts. In the 1870s the Yang family echoed that claim.[1] Some scholars assert this was done in order to connect their martial arts with a famous Daoist hsien. The actual founder of the taijiquan known today was Chen Wangting.[2]

Although folklore theorizes that Chen Wangting learned his taijiquan from Wang Zongyue, the student of Zhang San-Feng, the Chen family holds that Chen Wangting developed his skills from the teachings of Qi Jiguang (1528 – 1588), posthumously Wuyi, a military general of the Ming dynasty.

The Chen routines utilized theories of Daoist philosophy, Traditional Chinese Medicine, movements in the four cardinal directions and four corners, and coordinated breathing. Chen Changxing (1771–1853 CE) developed the two forms in use and taught by the Chen family today, the First Form and Second Form.

All five traditional schools, Chen, Yang, Wu, Sun and Wu (Hao), derive from the original Chen style taijiquan.

[1] (Wong, 1997; Wile, 1996; Bing YeYoung, 2006.)

[2] (Wile, 1996; Tang Hao, History of Chinese Wushu, 1935; Henning, 1981;

and Siaw-Voon Sim, 2002; Bing YeYoung, 2006; John Bracy, 2008.)

Yang and Wu Styles

Yang style is the second most senior taijiquan of the three primary styles, Wu being the third. Yang Luchan (1799–1872 CE) was a farm hand to the Chen family in the 1820s when Chen Changxing accepted him as the first non-family student of taijiquan. Yang returned to his home in Hobei Province and taught taijiquan to the locals. Later, Yang went to the capital in Beijing and taught his style of taijiquan to members of the royal palace guards and eventually, to the royal family.

Yang Luchan’s grandson Yang Chengfu (1883–1936 CE) finalized the standardized Yang style long form of taijiquan and was the teacher of the famous Cheng Man-ch’ing or Zheng Manqing (1902 -1975 CE), one of the first to teach taijiquan in the West. Yang Luchan was the teacher of Wu Ch’uan-yu or Wu Quanyou (1834–1902) and his son Wu Chien-ch’uan or Wu Jianquan (1870–1942 CE), the founder of the Wu style taijiquan.

The elder Wu was a Manchu hereditary cavalry officer in the Yellow Banner camp of the Forbidden City and an Imperial Guard in the Qing Dynasty. He opened his own taijiquan school in Beijing. The junior Wu was a cavalry officer and Imperial Guard, as well, and taught his style of taijiquan in Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Wu Yu-Hsing or Wu Yu-xiang (1812 – 1880 CE), a wealthy government official and student of Yang Luchan, was the founder of the other Wu (Hua) style taijiquan. Sun Lu-t’ang or Sun Lutang (1860-1933) was a student of Wu Yu-xiang and the founder of the Sun style, which was influenced by xingyiquan and baguazhang. Yang Chengfu, Yang Shao-hou or Yang Shaohou (1862-1930), Wu Quanyou and Wu Yu-xiang joined together to teach taijiquan at the Beijing Physical Education Research Institute.

New Perspectives

Although today there are a plethora of contemporary books with translations of source documents, scholarly histories and explanations of taijiquan, Jou, Tsung Hwa should be honored for his early publication of core texts of the three main styles. Chen style was illustrated by Chen Xin and published posthumously in a book called Chen’s Tai-Chi Chuan in 1933.

In 1934 the secrets of Yang style as taught by Yang Chengfu were published. Today these documents are available in The Essence and Applications of Taijiquan (2005). Wang Zhongyu’s (c. 1750) Treatise on Taijiquan, Wu Yuxian’s (1812 – 1880) The Theories of Thirteen Postures, sometimes attributed to Wang Zhongyu, and other classics can be found HERE.

The acclaimed scholarship of Lu Kuan Yu, a.k.a. Charles Luk, Taoist Yoga, Alchemy and Immortality and Jou, Tsung Hwa, The Tao of Tai-Chi Chuan, Way to Rejuvenation, describe very well the inner workings of traditional Daoist meditation, qigong, alchemy and taijiquan in their capacity as secular health modalities.

While the religious viewpoints and visualizations have been excluded from these explanations, the traditions are yet pseudo-science. Further investigation into Daoist exercises is warranted.

Like Western alchemy, Daoist alchemical operations could follow any number of steps. Whereas alchemy in the West often followed a seven or twelve stepped process, Lu K’uan Yu, or Charles Luk (1898 – 1978), described a procedure of eight operations from The Secrets of Cultivation of Essential Nature and Eternal Life, written by Zhao Bichen, or Chao Pi Ch’en (1860 – 1942.)

Charles Luk made Chinese symbolic alchemy accessible to English readers in Taoist Yoga: Alchemy and Immortality by decoding the original alchemical symbolism to terms more properly belonging to Traditional Chinese Medicine. It is the future task of modern science to further decode these claims into scientific language and provide notes on the real processes at work in these spiritual exercises.

Today taijiquan, like meditation and Qigong, is a global phenomenon practiced mainly for its health benefits. The rituals and visualizations of Daoist inner alchemy have been slower to gain interest in the West, and are therefore rarely published and difficult to find. As academics and the general public discover more about these obscure traditions, alchemical systems will become more accessible.

The world is becoming smaller due to advances in transportation and communication. Because of this, we can expect to see a renaissance of wisdom in the cosmopolitan sharing of ideas and disciplines between East and West. We are living in exciting times, the first witnesses to fascinating discoveries, as modern science is applied to ancient meditations.

For Further Reading

A Scientific Review of Health Benefits of Qigong and Taijiquan (Tai Chi)

Scientifically Measuring the Qi in Taijiquan

Wudang Daoist Internal Alchemy

Daoist Gate Traditional Wudang Daoism and Martial Arts

Wudang Daoist Traditional Internal Kung Fu Academy

Michael Saso, Taoist Master Chuang, Sacred Mountain Press, Eldorado Springs, CO, 2000

Wudang Daoist Religion in the West

Zhang Sanfeng — Legendary Founder of Tai Chi Chuan

An excellent site about Zhang San Feng with sources and a full bibliography.

The founders and exemplars of the various styles of taijiquan