My Zen: A Personal Journey

Face-to-face I see the top of Mount Tiantai;

Solitary in its height it stands above the common crowd.

Swaying in the wind, the pines and bamboo breathe in harmony;

When the moon shines the ocean tides roll continuously.

I look down below to the end of the green hills;

To discuss profundities, I have white clouds.

My happiness in the wilderness arises with these mountains and streams;

My original ambition was to enjoy fellow disciples of the Way.

My original ambition was to enjoy fellow disciples of the Way;

With fellow disciples of the Way, one can often get close.

Meeting, from time to time, guests who can overcome ignorance,

Daily welcoming visitors with whom one can discuss meditation.

Discussing the obscure on bright moonlit evenings;

Searching for the truth on mornings as the sun starts to rise.

When all teachings are destroyed without a trace;

Then one will know the original self.

Han Shan

Tumbling Into Meditation

My Zen began when I was eight years old. That is when my parents enrolled me at the local gymnastics club to begin training for competitive gymnastics. It was a career that ended when I quit at age fourteen before I might have been obligated to compete in the Junior Olympics. My heart wasn’t in it. Instead, I turned to meditation and the martial arts, seeking wisdom in the study of philosophy, history and politics.

A native of Iowa (go Hawks!) my main activity as a child was gymnastics practice. Training included multi-dimensional visualization of routines on six events, painful flexibility training, and ambitious acrobatic exercises. I enjoyed performing back flips with full twists, walking on the hands, holding difficult poses, and spinning around on a horizontal metal bar.

Gymnasts are judged to the tenth of a point on a ten-point scale. The form of every part of the anatomy and every skill of each routine is carefully analyzed. Gymnasts must be in complete control of their minds and bodies, balanced, aware and alert, and able to quickly recover from accidents.

We were taught to meditate to overcome fear, endure pain and prepare psychologically for our performance. This was an almost completely mental discipline of breathing, relaxation and mindfulness, with no particular posture involved. The meditation can be done sitting, standing, or walking in between practice sets or at any time in daily life. This state of mind is being cultivated in the Zen community in America and around the world.

Olympics | Gymnastics: Mikulak uses meditation in quest to be world’s best

Book: Becoming Mentally Tougher in Gymnastics by Using Meditation

Science Shows Gymnastics is the Most Difficult Sport in the World

Professional Star Athletes Who Meditate

Along the Way

After I quit gymnastics as a teen I started studying the Laozi, Zen Buddhism, yoga, and the Western Mystery tradition. In my late teens I meditated with my first Zen Buddhist monk and began my training in Wing Chun gungfu (kung fu) and Yang Style taijiquan (tai chi), taking an interest mainly in the meditative aspects of the Chinese and Japanese martial arts.

I continued Daoist and Zen Buddhist meditation, as well as astanga yoga, but for the next fifteen years I focused on Western philosophy, university and the Episcopal Church. I earned my Bachelor’s Degree in the Liberal Arts studying Business and Political Science at the University of Iowa. I was baptized, confirmed, and initiated into my life-long love of religious music, architecture and history.

Certain historic sites, whilst of no consequence to meditation or enlightenment, are meaningful in terms of appreciating the scope and history of human wisdom and meditation. There are quite a few pivotal sites I have yet to visit – shrines, temples and monasteries – but the locations I have seen have inspired me to always, as the Freemasons say, “seek more Light.”

Journey in the West

After college I enjoyed visiting historic religious houses such as, among others, the National Cathedral and St. Paul’s K Street in Washington, D.C.; Christ Church in Alexandria, Virginia; Christ Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Grace Cathedral in San Francisco; St. John’s Abbey in Minnesota; and St. Paul’s Chapel and Trinity Church Wall Street in Manhattan, New York.

Leaving the United States for a greater view of the world, I visited St. Basil’s Cathedral in the Red Square, Moscow, Russia; the Royal Chapel in Copenhagen, Denmark; Santa María la Blanca and the Museo Sefardí in Toledo, Spain; Notre Dame in Paris, France; the Abbey of Montecassino, the Pantheon and the Roman Forum in the city of Rome; and the sites at Vatican City, Italy.

In the U.K. my pilgrimage took me to Rosslyn Chapel in Midlothian, Scotland; Temple Church and Westminster Abbey in London, England; St. Alban’s Cathedral in Hertfordshire, England; and the cathedrals and several chapels at the English universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

You can read more about this on my very visual travel blog.

I studied Lectio Divina, the Christian monastic tradition of meditation, staying for short retreats at two different American Benedictine monasteries, one being Saint John’s Abbey in Minnesota, the largest monastery in the United States. I was welcomed graciously by the Roman Catholic monks, even though I was a chorister with the Episcopal Church (and not an especially good one).

I believe that the methods of Lectio Divina, which are also present in the Zen Buddhist tradition, are essential to a complete regular schedule of meditation. A deeper investigation of Lectio Divina will be posted in the future article, “Lectio Divina, Meditation of Christian Monks.”

My interest in meditation blossomed when I joined a Mystery School lodge of Freemasonry in Washington, D.C. I was made a Mason in a courtesy third degree ceremony by Alexandria-Washington Lodge No. 22., named as such because George Washington served as the first Master of the lodge.

I also became a 32nd degree Freemason in Alexandria, Virginia. I regret that I had not much time to become deeply involved with the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry before leaving to start my family in my wife’s native country, Indonesia.

Zen Buddhist Meditation

In one sense, Zen meditation has no goal; zazen is simply the natural state of awakened being. In another sense, the ultimate goal of meditation is Samadhi. This is a common term used in the various Hindu, Jain, Sikh, yogic and Buddhist schools. For thousands of years, meditation has been known as a three-fold process: Dharana, or concentration; Dhyana, meditation; and Samadhi, enlightenment.

The Sanskrit root Sam means ‘together’ or ‘united,’ and dhi is ‘consciousness.’ Samadhi, then, is when the mind pulls itself together to become whole. Samadhi is the consummation of concentration, when the mind is still. It is the state of awareness in the present moment. It is translated as enlightenment or illumination. “Buddha,” itself, means “enlightened one.”

The man we know as Buddha was a sixth century BCE clan chieftain in an area that is today divided between Nepal and India. Siddhartha Gautama, later known as the Buddha, called the school he founded Dhamma-Vinaya, or Truth-Discipline. Science Abbey articles follow the monastic order he established from its origins in India, to its Chinese roots, and to the Korean, Japanese, and Western branches of Zen.

Further articles will delve into various other kinds of meditation around the world. My Zen, or my meditation, has developed of necessity from various traditions, to a path of scientific discovery.

Beginning Zen

In 2004 I began zazen, sitting meditation, with a Korean Jogye Order monk named Pohwa Sunim, founder of the World Zen Society and founder of Potomac Sangha in Alexandria, Virginia. Korean Soen Buddhism is better known as Japanese ‘Zen,’ Chinese ‘Chan,’ or Sanskrit ‘Dhyana,’ meaning “meditation.” I think the most popularly known name is ‘Zen,’ which is the term I generally use.

Every week Sunim sat Zazen, drank green tea, gave a sermon known as a Dharma Talk, gave koans for his students to chew on (koans are short enigmatic stories, usually about ancient masters and monks, meant to be understood by non-intellectual means), and met with students privately to discuss their progress. He actively pioneered having such discussions via email, believing in the capacity of new technology to aid in communicating the message of Zen.

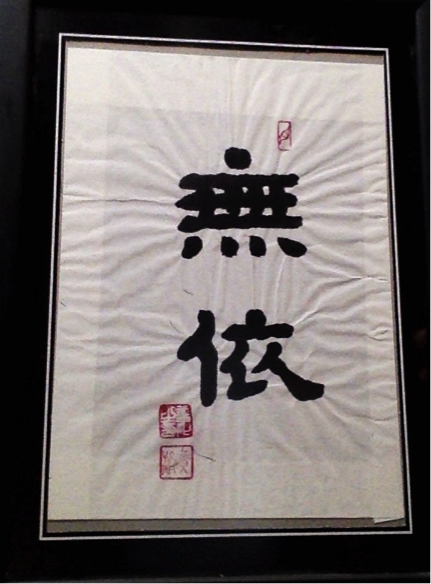

I received my dharma name Wu Yi (“Depends on Nothing”) with Potomac Sangha on the banks of the Potomac at Belle Haven Park in Alexandria in celebration of Vesak Day (Buddha’s birthday) on Sunday May 28, 2004. I took the Upasaka vows (lay ordination vows) of Zen Buddhism. The vows are to take refuge in Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha; and to realize the five precepts: not to kill, steal, misuse sex, lie, or misuse intoxicants.

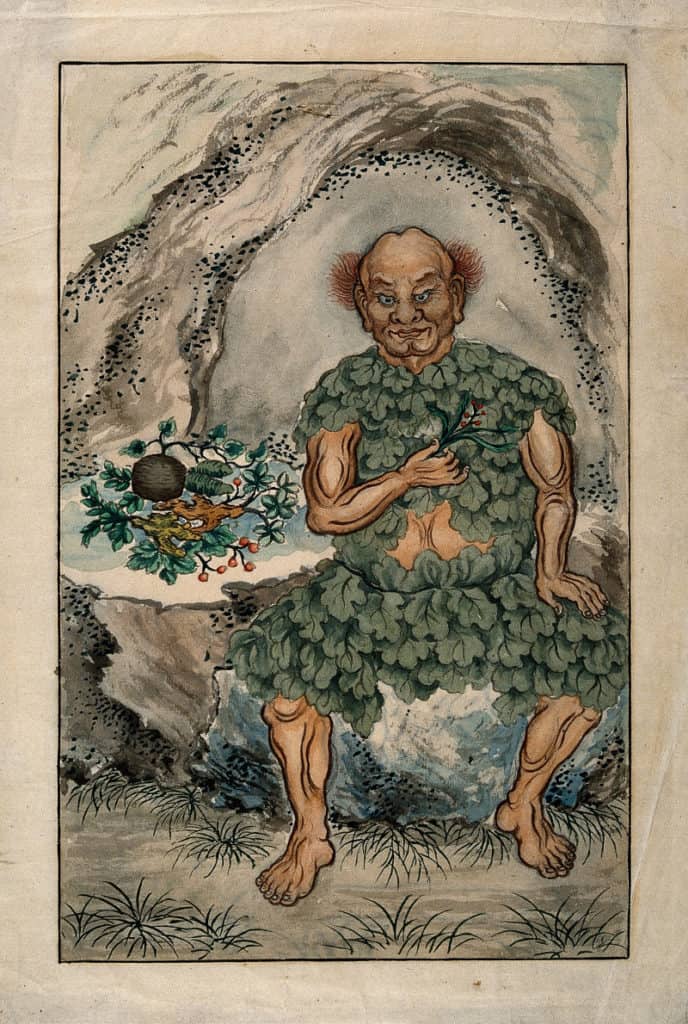

My Korean Seon teacher, Pohwa Sunim, was a monk trained in South Korea to teach his own authentic lineage to Americans. He had also studied with Zen monks in the mountains of Japan. Students would get private time with Sunim face to face or email to address their koan. Pohwa Sunim never mentioned any literature, but he did introduce me to Han Shan, the Tang Dynasty recluse and poet who wrote in the Daoist and Chan (Chinese Zen) traditions.

Pohwa Sunim began each session by making and sharing tea. The class, called the “sangha” in Buddhist terminology, would chant the Heart Sutra. The sangha would do zazen sitting on our meditation cushions (“zafu”) and do walking meditation. Sunim would give a “dharma talk” and answer questions. Sunim gave everyone their own koan, such as:

A student asked Master Yun-Men, “Not even a thought has arisen; is there still a sin or not?” Without hesitation, the master answered, “Mount Sumeru!” Why did the master answer, “Mount Sumeru?”

When I took the sixteen precepts of the vows of Soto Zen lay ordination in 2020, my sensei had my Chinese Dharma name, Wu Yi, translated into the Japanese Mui. Since then I have been studying and practicing with this American sangha (community) of the Katagiri-Winecoff lineage of Japanese Soto Zen Buddhism.

Buddhist Temples

Appreciating my experiences with cathedrals and churches in Europe and America, I also had the privilege of visiting temples in China, Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, Thailand and Indonesia. I had the pleasure of meditating at the Temple of Heaven in the Forbidden City, home of the Chinese emperors in Beijing.

My pilgrimage brought me to the Daoist Louguan Terrace at Mount Zhongnan in Shaanxi Province, where Laozi is supposed to have written the Daode jing. It led me to White Cloud Temple in Beijing, the headquarters of the Chinese Daoist Association. On route was also the prominent Daoist Tai Shan (Mount Tai) Monastery in Shandong and Confucius’ Tomb in Qufu City, Shandong.

I visited the White Horse Temple, the first Buddhist temple in China, and the Shaolin Monastery, where Chan/Soen/Zen Buddhism and kung fu were born. I have been to Longshan Temple in Taipei, Taiwan. I travelled to Po Lin Monastery and the Tian Tan Buddha on Lantau Island, Hong Kong and stopped at the daoist Wong Tai Sin temple in Hong Kong.

I have had opportunity to enjoy the Hindu Sri Krishnan Temple and the adjacent Chinese Buddhist Kwan Im Thong Hood Cho Temple on Waterloo Street, Singapore.

I’ve also found my way to the ancient Buddhist temple ruin at Ayutthaya, the capital of Siam 1350-1767, outside of Bangkok, and the reclining Buddha at Wat Pho, as well as the royal Chapel of the Emerald Buddha at the Grand Palace in Bangkok, Thailand. I explored Sensō-ji Buddhist temple in Asakusa, Tokyo, Japan, Tokyo’s oldest temple, originally of the Tendai sect, dedicated to Guanyin, the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy.

In Indonesia I meditated at Borobudur in Yogyakarta, the 8th-9th century Buddhist temple with 72 stupas with buddha statues inside; and two temples in Jakarta on the island of Java: the Chinese klenteng Kim Tek Ie Temple and the Buddhist Vihara Mahavira Graha Pusat. I also explored the Hindu Pura Besaki temple complex on the slopes of Mount Agung in Bali, and the Tanah Lot temple in Bali.

Read more about this on my very visual travel blog.

Soto Zen and an Online Community

After relocating to Indonesia and living there for ten years, I was finally able to focus again on my Zen practice. Unfortunately, there is no Zen community, or sangha, in Jakarta, where I am staying. When I searched the World Wide Web for a Zen teacher in the winter of 2018, I found an online Soto Zen sangha called Treeleaf Zendo, founded by an American Zen monk living in Japan by the name of Rev. Jundo Cohen.

In the spring (Saturday, April 6, 2019) I participated in my first online Zazenkai with Treeleaf Sangha, an hour and a half of sitting Zazen, walking meditation (Kinhin), chanting, and a short dharma talk. Jundo is a Dharma heir of Gudo Wafu Nishijima (1919-2014).

Nishijima Roshi was a dharma heir of Master Rempo Niwa, abbot of Eihei-ji temple and head of the Soto Zen School of Buddhism. Rev. Nishijima was also a student of the influential monk Kodo Sawaki (1880-1965), a professor at Komazawa University. Sawaki Roshi was known as “Homeless Kodo,” because he taught at temples all over Japan rather than remaining at a single temple. Jundo’s zendo in the country is all secluded charm and an ideal niche for Zazen.

Rev. Jundo not only started an online sangha such as I needed, but he was getting out the message about the compatibility of Zen and science. I read a few articles suggested by Jundo on Facebook and began to make more sense of Soto Zen as an institution.

I began to understand Zen meditation in a different way. Shikantaza, the Soto Zen term for meditation, means “nothing but just sitting.” It is best described by the founder of Soto Zen in japan, Eihei Dogen Zenji, in the Fukanzazengi, or Principles of Seated Meditation. I began sitting Zazen for half an hour six days a week.

When I went home to the Midwest United States, I visited Ancient Dragon Zen Gate (ADZG) in Chicago in 2018, where the service was led by Rev. Taigen Dan Leighton. I was not aware at the time of his career or translations of the work of Dogen Zenji, the founder of Soto Zen in Japan, but his dharma talk was deeply meaningful.

After later receiving by order Rev. Leighton’s translation of Dogen’s rules for the Zen monastery, the Eihei Shingi, and having read his article “Zazen as Enactment Ritual,” I then recognized his name and looked at his online bio. Every serious English-speaking Zen practitioner will be familiar with his contributions to Zen scholarship.

The Dragon Gate

In 2019 I returned to the States and passed through Chicago, visiting ADZG again, and at the end of my trip I went to the Iowa City Zen Center for some morning Zazen. After sitting, the sangha sat down with the teacher, Rev. Dainei Appelbaum, for some tea and conversation. A week later my family and I were on our way to the Ryumonji Zen monastery in northern Iowa and the remote Hokyoji Zen Practice Community in southeast Minnesota.

Hokyoji was envisioned as a model of Eiheiji, one of the two head temples of Soto Zen in Japan, by the late Rev. Dainin Katagiri Roshi (1928-1990). Katagiri Roshi was one of the first few Soto Zen Buddhist monks to bring Zen from Japan to the United States of America. After helping Shunryu Suzuki Roshi in California establish the first ever Soto Zen monastery in the U.S., Katagiri Roshi went on to found the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center in 1972.

In 2007 Shoken Winecoff Roshi, a first generation American Zen monk and dharma heir of Katagiri Roshi, founded Ryumonji, which means, “Dragon’s Gate Monastery,” in honor of his teacher Katagiri Roshi’s intentions to build a traditional Japanese-style training monastery for American monks and spread the teachings of Zen Buddhism in the Midwest.

Ryumonji, designed as a traditional Japanese Soto Zen temple, sits peacefully amongst the green hills of Dorchester in northern Iowa. It now enjoys affiliated Zen centers in Iowa, Minnesota, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, Missouri and Colorado. Since beginning training at Ryumonji, it is clear that this spiritual sanctuary is fulfilling Katagiri Roshi’s intentions.

The Science Abbey

As a librarian and historian, I enjoyed doing research acting as a resource for people. With Science Abbey I can offer as a service a large amount of data condensed into a short account. The result is probably more useful than it is entertaining. When we are seeking wisdom this is what we encounter and we must engage with it.

No matter their age, young or old, everyone is always learning. While some things can only be known by looking within, other things we can only learn through others. It is important that we research diverse sources and use critical thinking when developing our world-view.

Once people around the world accepted the isolation required by the COVID-19 pandemic, many communities, from schools to businesses to religious organizations, formed online video chat groups to join in regular meetings. This has somewhat normalized video chat in modern society, which is another step toward connecting people all over the globe. I hope Science Abbey will serve to help inform this ever-awakening global community.

It is a joy to bring together these ancient traditions of Orient and Occident as they have developed in the United States of America, to pioneer a way of life that embraces the teachings of the globe and yet remains just beyond words. We will one day see how this merging at the deepest levels of the roots of East and West blossoms into a tradition without race, nation, or denomination: a “monastery without walls.”

There are many important temples and monasteries I still want to see and people I would like to meet: my travels are far from over. Maybe I’ll see you along the way.

Read more in the Science Abbey BLOG