IN THE BEGINNING…

It is interesting to me that at some point when the world was young, before industry, before electricity, and previous to the global domination of the major religions, somebody sat down and began to meditate. It happened in India during the birth of one of the first urban centers in a cradle of civilization.

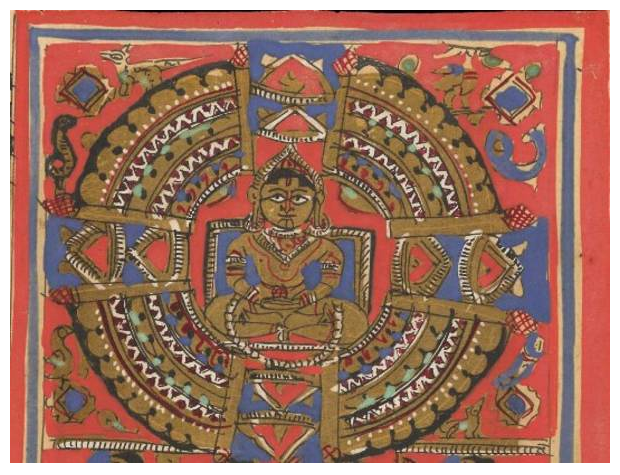

The earliest form of meditation in recorded history was Indian yogic meditation, which is depicted in Indus Valley Civilization art as early as 2,500 BCE. The Pashupati seal found at the Mohenjo-daro archeological site shows a horned god or yogi meditating surrounded by animals.[1]

It was a period when humans everywhere lived surrounded by the sounds, sights and smells of nature. It was not paradise, but it was a world, as the seventeenth century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes famously described, with “No arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death: and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.”

I wonder who it was and what the circumstances were, exactly, when some person in India sat cross-legged, relaxed, concentrated, and first set upon the path of enlightenment.

My personal experience with yoga is unfortunately relatively slim. When I took my first yoga classes in my early twenties the exercises felt familiar. Yoga is very much like the discipline of gymnastics that I trained in for six years as a child, especially the floor exercise, my favorite event. We learn how to stay calm, relax, breathe, concentrate, maintain a slightly uncomfortable pose and transition to the next pose.

The yoga I have practiced for twenty years was learned from a class on Yoga Chikitsa with a yogini from Napa Valley, California. This is the beginning or primary series of Astanga Yoga as taught by Sri K. Pattabhi Jois and his teacher Krishnamacharya. I have taken yoga classes in Bali, Indonesia, as well, and with over thirty years of practice, I’ve developed my own routine with poses that suit me.

Yogic Meditation

The word ‘yoga’ is derived from the Sanskrit words yujir yoga, “to yoke” and yuj samadhau, “to concentrate.” It means generally “to unite.” The one who meditates is concentrating and bringing together the whole mind. This act of mystical absorption eventually results in the individual mind transcending the illusion of duality and seeing its essential unity with the cosmos. Yoga practitioners are called yogins; men are yogis and women are yoginis.

The highest goal of meditation is Samadhi. This is a common term used in the various Hindu, Jain, Sikh, yogic and Buddhist schools. For thousands of years, meditation has been known as a three-fold process: Dharana, or concentration; Dhyana, meditation; and Samadhi, enlightenment.

The primary Sanskrit term for meditation is Dhyāna, the root of which is Dhi, the vision of the imagination, associated with Saraswati, the goddess of knowledge, wisdom and poetry. Dhāraṇā is concentration with controlled breathing. Its object can be an idea, a god, an object or even a point, such as the tip of one’s nose or one’s center of gravity.

Dhyana is the contemplation of that which Dharana has used as a focus for prolonged concentration. Dhyana sustained in Dharana is called Samadhi. In Samadhi, the culmination of Dharana and Dhyana, one is aware in the present moment with singleness of mind, the mind absorbed in meditative oneness.

The Sanskrit root Sam means ‘together’ or ‘united,’ and dhi is ‘consciousness.’ Samadhi, then, is when the mind pulls itself together to become whole. Samadhi is the consummation of concentration, when the mind is still. It is the state of awareness in the present moment. It is translated as enlightenment or illumination.

The earliest references to meditation originated with the Hindu Vedas of India, as in the oldest Indo-European literary and philosophical landmark in the world, the Rig Veda, which gives us the well-known Gayatri mantra (3.62.10): “Let us meditate on the excellent glory of the divine sun/light; may he enlighten our understanding.”

Meditation systems developed with the Hindu Upanishads, especially the Kaushitaki, Chandogya, Brihadaranyaka, Maitreyaniya and Prashna Upanishads. The practice of meditation was also anciently examined by the Jains and Buddhists in India, and the Chinese Daoists and Confucians in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE.

The origins of meditation are lost in the mists of time, but the concept of Dhyana is found in the Rig Veda, the Upanishads, Jaina texts, Buddhist manuscripts and later sutras such as the second to fourth century CE Patanjali’s Yogasutras. It is with the people of these traditions that deep meditation first became a religious practice.

The Vedas:

Ancient Philosophy, Magic and Yoga

India has been a land of diverse ideologies, but the first and principal manuscripts on Indian religion, the Vedas, have had an effect on every one.

The Indian Vedic hymns were written in the 16th century BCE but are speculated to be based on ideas prominent 2,500 BCE. The Vedic period lasted from then until about 600 BCE, marking the settlement of the polytheist Aryans from the Caucasus Mountains of central Asia and their integration with the natives of India.

The Vedas were the literature of the poets, priests and philosophers. According to tradition, the compiler of the Vedas was the dark-complected sage Vyasa, a figure introduced in the Mahabharata and still revered to this day. With some Caucasian influence, the Vedas had much in common with Mediterranean, Celtic and Nordic cultures. The interest of Indian philosophy in this early period evolved historically in a natural progression from the complexity of polytheism, to the simplistic duality of monotheism, and then in the Upanishads on to the cosmic, unknowable oneness of monism.

Ancient Vedic hymns to the gods declare that in the beginning existence arose from nonexistence. They describe an unborn, primeval One that existed before heaven and earth and produced all things. All gods, in fact, are but titles given the One by the sages. This One is Lord of all things, the unknown god that established eternal law. Truth, law and justice were represented in many forms, including the god Soma, a sacred hallucinogenic elixir of immortality drank by the gods and by mortals in Vedic ritual.

The Hymn to Purusha, the Cosmic Man, describes the immortal god of life, whose body was part in heaven and was part the living creatures of the earth. In language resembling alchemical symbolism, it is written that:

The moon was born from his spirit,

from his eye was born the sun,

from his mouth Indra (thunderstorm) and Agni (fire),

from his breath Vayu (wind) was born.[2]

The ancient Vedic magicians healed through spells and incantations against evil spirits and evil magicians, as evidenced in the earliest Vedas. Brahmin priests were the physicians until the Muslim conquest of India, about the turn of the first millennium. The Brahmins were adept surgeons and pharmacists, but while their spiritual anatomy was quite extensive, physical anatomy was lacking.

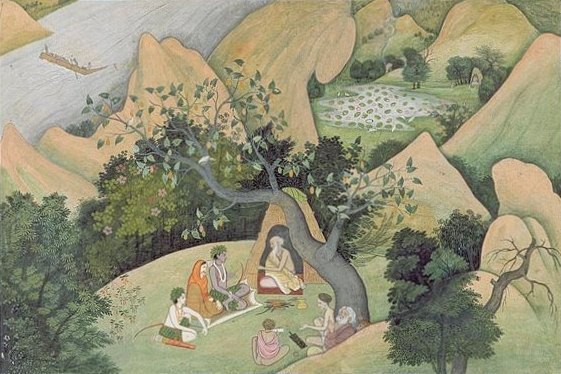

There are four Vedas, each of which contains hymns, ritual and sacrificial duties, and philosophical writings. The Vedas introduced the practice of magic. Also, they set the foundation of the social order that was to persist to the twenty-first century, which encourages the aged householder to retire to the forest, and the forest-dweller to practice meditation.

The oldest Veda is the Rig Veda, ancient hymns about the gods, around which the later Vedas are based, written as early as 1,500 BCE. The Yajurveda focused on ritual, the Samaveda expressed scripture as chants, and the Atharvaveda is a collection of hymns teaching magic, religion and medicine for daily life.

[2] Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli and Moore, Charles A., A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy, Princeton University Press, 1989, p. 20.

The Rig Veda: The Gods and Creation

The Rig Veda is the story of Creation; a thorough account of the basic forces the Aryans in India observed in nature. Notable are Vishnu the all‑pervading Creator deity; Vayu the wind, breath or soul (atman) of the gods, first‑born, “Germ of the World;” Indra the thunderstorm and Lord; and Agni the god of fire and creation.

Other primary gods included Prthivi the Earth and Dyaus the Sky; Surya the sun; Vak the voice or Speech; Brhaspati; the god of domestication, the Lord of priests and prayer. There was Varuna the Absolute; Visvakarman the Creator; and the Visvedevas, the whole pantheon. Prajapati was the spirit of Creation and Life, Purusa the spirit of creation and soul of humankind, and Yama the King of the Dead. Brahman was the conscious Creator and Lord of the Universe: Atman was the personal soul.

The ancient Indians understood the principle of Rita, the universal law, order, justice and virtue. Moral and ethical behavior was based on understanding of Rita, and the ultimate attainment for the elite, the priestly caste of Brahmans, was to align the personal soul, or atman, with the universal creator, Brahman. Vishnu is the Sustainer of Creation and is the symbol of good. He was incarnated on earth to redeem the good when life became bad. His incarnations were first animals and his later were men.

Krishna was an incarnation of Vishnu, as was Rama, the Ideal or Perfect Man and King, and Buddha. The final incarnation of Vishnu is prophesied Kalki, who will come with a sword on a white horse, to end the present evil age and initiate a new age of peace. Shiva was the law of change, or ‘destruction’ as opposed to ‘creation.’ His concubine Shakti was the earth, or manifested as Kundalini, life-force. In ancient India Dharma was the cosmic law and order. The ‘Tree of Dharma’ had its roots in the sky (heaven) and its branches were the earth.

The Indian sage practiced yoga, the method of uniting the divine and the earthly, or God and man. Brahman’s spirit, or prana, was the substance of Creation. The cultivation of prana was accomplished by consistent study and contemplation of Vedic scripture, and later, philosophical texts called the Upanishads, the Mahabharata, and the Sutras. Prana was also cultivated through breathing exercises, postures, and mental exercises, diet, holistic medicine and a natural lifestyle.

The Epic Period

The next stage in development of Indian mystical philosophy was the Epic Period from 600 BCE to about AD 200. About half of the Upanishads were written down during this period (five of them being passed down orally from 800 BCE) and the other half were composed up to the fifteenth century CE. The Upanishads are known as Vedanta, meaning “the end of the Vedas,” and each Upanishad is associated with one of the four Vedas.

Upanishad means literally to sit together, which refers to students sitting around a guru (teacher), to learn spiritual wisdom, with the implication of esoteric doctrine or secret teachings. Although the Upanishads are variously attributed to different sages, the actual authors are anonymous, and exact dating is unknown.

The Upanishads develop the idea of the unity of the universal absolute, Brahman, and the true, absolute self, Atman. Brahman is both the incomprehensible reality that is absent of qualities, and the knowable creator or personal god, Ishvara.

These writings distinguish between the way of ignorance and selfishness that leads to temporary pleasures, and the way of moderation and self-control that leads to wisdom and the ultimate goal of existence, self-realization. Self-realization is identified as the mystical revelation of oneness with the divine, true immortality. It was this Vedanta philosophy that informed Buddhism as it was developed by Gautama Buddha.

Epic Ideas

The Epic Period produced the Ramayana, Samkhya, the Mahabharata, the Laws of Manu, and the Dhammapata of the Buddha. The Ramayana was the epic poem of King Rama, the incarnation of Vishnu. In the Ramayana, a mythical deity is created to represent the perfect human manifestation of mystical revelation.

Rama is the incarnation of the Lord, the personification of godhead, and he is the ideal king. He is immortal as god, yet incarnate as man. He practices, indeed embodies, the virtues that lead to peace and good order in self and in society. He represents the goal of human accomplishment and his story is instruction on how to attain that goal.

The Mahabharata contained the popular Bhagavad-gita, the first comprehensive treatise on yoga. During the Epic Period the people turned to the reverence of the god Shiva; the god Vishnu and his incarnations as Krishna or Rama; or the teachings of the Buddha. This was also the period of Zoroaster in Persia; Pythagoras, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle in Greece; and Confucius and Laozi in China.

At the turn of the millennium the sutra literature appeared, systematic and critical philosophical discussions and debates, and the scholastic commentaries upon them. This philosophical productivity in India started about the time of Christianity in the West, and continued until the sixteenth century, when Arab Muslim and then British Christian invaders persecuted and subdued Aryan Indian culture.

The sutras were manuals of philosophical rules or formulas, like Patanjali’s system of yoga in the Yoga Sutra. Previous philosophical literature was systematized and exposed to critical interpretation. Following this period, scholastic study of Indian philosophy has been the rule.

Samkhya Philosophy

The legendary Kapila, of divine origin, is said to have invented the philosophy of Samkhya, which was the first real system of contemplation. Whereas yoga would later seek liberation from ignorance and suffering through meditation and exercise, Samkhya taught liberation through knowledge. It taught that the world is the maya, or cosmic illusion which exists due to ignorance.

The practitioner’s goal is moksha, to release himself from karma, the effect of one’s actions, or destiny, and from the cycle of transmigrations of the soul, or reincarnation. Suffering leads to a yearning for salvation, until even pleasure is pain because it is followed by pain.

The aim of Samkhya is the separation of purusa, self or spirit, from prakrti, nature; the isolation of the essence of oneself from all that is not the self. The spirit contemplates itself; it withdraws from matter into itself, and all elements that are not the spirit are reabsorbed into nature. Liberated, the material body continues but the personality has escaped.

Thus the person lives out their karmic existence until they die and their spirit is annihilated. Only when the last sentient being has attained salvation will the universe be reabsorbed into its original substance.

Manu

The Laws of Manu expand on the hierarchical rules of the Vedas and make the Brahmin, or priest, the superior human being. While kings ruled over the lower temporal realm, the priests stood between the divine and all castes of people. The priest was a powerful magician who performed the sacrifices that determined public well-being and personal fortune.

Manu is the Creator, or the Lord of creatures, and his body is the entirety of the castes of man, his mouth the priests, his arms the kings, his legs the common man, his feet the servants. The Aryan nobleman was taught that Manu was the perfect example of human being, and to follow his written laws was the way to Brahma, the highest level of existence.

Manu taught the Brahmin to sit in single-minded concentration and visualize the whole system created by the Self-existent One. He saw the Lord as energy and matter, the law unmanifest and manifest, darkness and creation. He witnessed the Primordial Human in the Egg, and the Egg divided in two, heaven and earth. He visualized the six elements: ether, light, wind, water, earth and mind; the eight cardinal directions of the atmosphere and the waters, the heart-mind out of which grew the ego or the sense of self, the “I am,” the senses, sense organs and motor powers.

From the Primordial Human came the gods who have the breath of life, whose essence is ritual. From him came time, the planets and the stars, the sea, rivers and mountains, prana, speech, erotic pleasure, desire, anger, and all the opposites.

From the elements he created all living beings, which are created again and again according to their form, like the seasons. He knew that from the breath of life came the dharma or duty of the four castes, of man and woman, throughout the epochs and the calendar, and that his religion and its transformative rituals were the root of prana and comprised proper conduct.

The universe and man may be divided into three gunas, or modes of being. Tamas is inertia, rajas is energy or passion, and sattva is goodness. The goal is to find the balance, which is sattva. The Bhagavad-gita names this goal yoga, and presents the yogin as the supreme person. It sets forth the discipline of yoga somewhat more systematically than the literature before it, to teach one how to accomplish and perpetually maintain mystical revelation even in daily activity.

The Yoga Sutra

Patanjali, the father of yoga, described yogic meditation in terms of purusa, self or spirit, and prakriti, nature. Yoga was purification. It was primarily a discipline of the mind, a form of concentrated contemplation or trance with the aim of uniting consciousness with God. Patanjali defined his method as Dharana, or concentration; Dhyana, or meditation; and Samadhi, or trance, taken all together as Samyama, or inner discipline.

Patanjali recommended meditating on various subjects, such as friendliness, the sun, the moon, the polestar, the navel, the throat, the heart, prescience, the relationship of the body and space, and other topics. He did not give instruction pertaining to postures or breathing exercises; this was to be introduced by the authors of hatha yoga and tantric yoga literature.

The Yoga Sutra, composed circa 200 BCE – 200 CE and attributed to Patanjali, describes an even more methodical system of enlightenment than that developed by the Buddha. Yoga shares with Samkhya the goal of the separation of purusa and prakrti. The Yoga system is thus a purification and a return to the original state of being. Yoga encompasses the yogin’s entire life as an ethical code and health regimen as well as a meditative discipline.

The aim of meditation is complete samadhi, a state of concentration or trance, and contemplation, which leads to enlightenment. The calming effects of ethical conduct and a degree of health help to facilitate meditation. Yoga introduced special postures and breath control exercises to aid concentration. All forms of Yoga begin with Astanga, the eight limbs, or preparations. In Patanjali’s Yoga Sutra the eight limbs of raja, royal or classical, yoga, are part of a single process that sets the foundation for true meditation.

- Yama – virtue, moral code of conduct; which includes respect for all living beings, honesty, restraint of envy, lust, and impatience, moderation of diet, simplicity, purity, and loving-kindness;

- Niyama – religious observances; which includes ritual purification, charity, study of the scriptures, worship, mantra, sacrifice and other religious observances

- Āsana – posture

- Pranayama – breathing exercises; regulation of breath and life-force

- Pratyahara –subjection of the senses; withdrawal of the senses of perception

- Dharana – concentration; one-pointedness of mind

- Dhyana – silent meditation

- Samādhi – ecstasy; tranquility and holistic awareness

Buddhism and Yoga are not just philosophical systems, but practical applications of theories of holistic medicine, which complement the Indian form of medical practice called Ayurveda, as taught in Tantras and Samhitas. The eight branches of Ayurveda were formalized as:

- Internal medicine

- Surgery

- Ears, eyes, nose and throat

- Pediatrics

- Toxicology

- Purification of the reproductive organs

- Health and Longevity

- Psychiatry and Spiritual Healing

The physical and mental exercises of yoga are still unsurpassed, and have had an influence on modern Western medicine, i.e., hypnotism, chiropractic, and alternative or complimentary medicine like “Healing Touch,” no less than on Western culture, itself, which has fully absorbed yoga as a modality of health and meditation. There are many different yoga schools that teach varying methods of yogic exercise.

Hatha yoga, one of the main branches of yoga, is practiced as a series of postures called asanas. A yoga routine usually follows a pattern such as that of the Surya Namaskara, or Sun Salutation, which links together twelve poses. To learn yoga, one should locate a lineage yoga teacher and be sure the practices one follows are approved by one’s physician or healthcare provider.

Read “Tantric Yoga: Philosophy and Meditation”

Modern Yoga

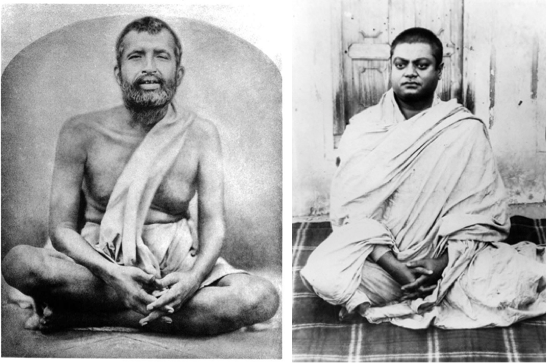

The Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in 1893 was the first global interfaith gathering and occasion for formal interfaith dialogue. The conference introduced several religions to the general public of the United States, including Jainism, Theravada Buddhism, Zen Buddhism, and the Bahá’í Faith. Swami Vivekananda, a sanyassi monk and great teacher of Vedanta and Yoga, represented Hinduism.

Vivekananda went on speaking tours in the U.S. and the U.K., successfully promoting Hinduism in the West as well as in India. One hundred years after the original Parliament of Religions the institution was revived and has met six times up to this day.

Other swamis taught in America from the 1920s. Just to name a few, Tirumalai Krishnamacharya (1888 – 1989), known as the father of modern yoga, was an Indian philosopher, yoga teacher, Ayurvedic healer and author. Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895 – 1986), declined the position of future world leader prophesied by the Theosophical Society, but made his mark teaching yoga to the West and associated with the likes of Aldous Huxley, Charlie Chaplin and Bernard Shaw.

Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (1918 – 2008), made Transcendental Meditation popular in the 1960s with the help of the famous rock band, the Beatles.

In the 1980s the number of yoga practitioners in the West boomed as yoga was marketed as a secular and mainstream system of exercise for health and healing. At the turn of the millennium there was another surge and today over 20 million people practice yoga.

Following in the footsteps of his predecessor, the popular 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, practices his Tibetan Buddhist Tantra yoga with thousands of monks and promotes this form of meditation around the world. Most yoga in the West today is health oriented and taught by Western students or students of students of well-known Indian gurus.

The Future of Yoga

The yoga the author has practiced for twenty years was learned from a single class of Yoga Chikitsa with a yogini from Napa Valley, California. I only learned the beginning or primary series of Astanga Yoga as taught by Sri K. Pattabhi Jois and his teacher Krishnamacharya. I then practiced with the aid of a book Power Yoga: The Total Strength and Flexibility Workout by Beryl Bender Birch (Simon and Shuster, London, U.K., 1995).

This introduction to yoga was supplemented with study of Indian philosophy and practice of methods in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, the Shiva Samhita, and other translated Indian texts on yoga. Later, I took yoga classes in Bali, Indonesia, and with further research into the science of yoga, I developed my own routine.

Although I practiced with various teachers, never having had a guru, I certainly do not possess any authority in authentic Indian yogic technique. My personal yoga is informed by my experience with Western gymnastics, Chinese kung fu and Daoist taijiquan, and Zen Buddhist meditation.

With the meeting of the West, Indian philosophy has incorporated Western thought into its fold and developed new systems, and the West has done likewise. Contemporary Indian philosophy tends to remain open to Western influences, just as the West has synthesized many aspects of Indian culture with its own mainstream culture, especially through yoga and Buddhism.

The future of philosophy lies in an integrated and holistic worldview that incorporates and transcends denominational traditions. It will focus on holistic health, psychology and meditation. The philosophy of the future aligns with science and universal human rights, and may properly be identified as secular scientific humanism, but it will not lose sight of the wisdom and achievements of the past.